Recent controversy over the government’s plans to review the way in which MP’s conduct is dealt with highlights the importance of a fair and independent review system and the dangers of changing the proverbial goal posts before individual cases are concluded.

MPs are not employees and do not have the same employment protections requiring concerns about their conduct to be dealt with fairly. MPs have substantial investigative safeguards in respect of conduct allegations made against them in the form of independent reviews of their conduct by the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards and the Commons Standards Committee. Together these parliamentary watchdogs conduct independent investigations and reviews and recommend what, if any, action should be taken when MPs breach their Code of Conduct.

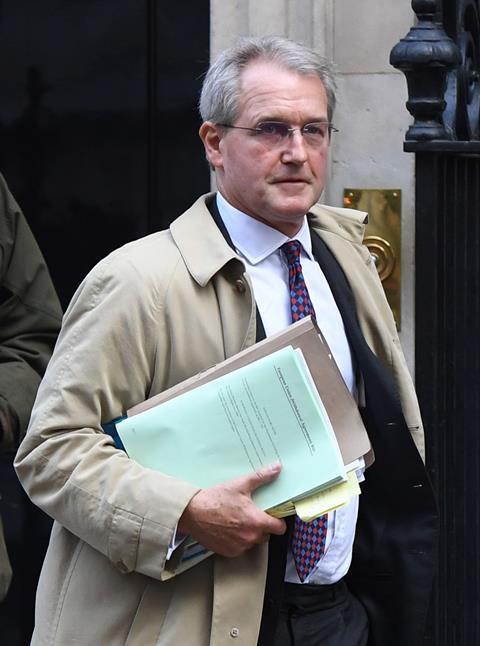

The report in respect of Owen Paterson’s conduct results from a detailed inquiry by the Parliamentary Commission opened in October 2019 alleging Mr Paterson had lobbied for two companies for which he was a paid consultant and had therefore breached lobbying rules set out in the MP’s Code of Conduct.

All seems relatively straightforward in respect of an independent and thorough investigation.

What happened next however in respect of the Paterson case has been well publicised and, although MPs are not employees benefitting from employment protections, the case does create an interesting parallel with lessons that can be learned by employers in how they deal with fair process.

If an employer decided midway through an employee misconduct investigation to carry out a wholesale review of its disciplinary policy, with the consequence of halting the progress of that individual’s case for an indeterminate period, many would question the fairness and rationale of the timing.

Yet this is what the government saw fit to do in the Paterson case where the independent Commons Standards Committee had already determined there had been multiple breaches of lobbying rules.

Although the government exercised an embarrassing U-turn in their initial plans to overhaul the conduct review process, the controversy raises many questions about natural justice and fairness when carrying out conduct investigations in a workplace environment.

The right to a fair hearing is a fundamental human right and that extends to employees being able to put forward their representations during a fair, thorough, transparent and objective investigation and any subsequent disciplinary process that is likely to lead to a sanction being given. Paterson had the ability to make representations during his investigation but what appears to be lacking from the MP conduct system is the right to appeal the Standards Committee findings prior to recommendations being made about sanctions.

In the employment arena the right to appeal a disciplinary outcome forms part of a fair and reasonable disciplinary policy and without it employers are likely to be unsuccessful in defending allegations of unfair process in unfair dismissal tribunal cases even if the substantive conduct elements themselves are proven.

Another fundamental lynchpin of a fair investigation and disciplinary policy is clarity. An employee is entitled to be made aware of how matters will be investigated and what outcomes and sanctions are tabled. If an employee was informed midway through their disciplinary that the process was being paused whilst a generic review of the process was being conducted it would be expected that the cries of unfairness should be deafening.

Any review that causes delay to a disciplinary outcome and communication of that outcome will not accord with fairness principles. The key principles of a fair employment disciplinary process are set out in the Acas Code of Practice on disciplinary procedures. One of those principles is that meetings, decisions or confirmation of decisions should not be unreasonably delayed. Where an employer is found not to have followed the Acas Code of Practice this will be taken into account by an Employment Tribunal in determining not only the fairness of the process but also whether any additional compensation should be awarded to the employee.

If an employer has concerns about the disciplinary system it operates it will be laudable to carry out a review and make relevant changes. However, that would not be done part way through an individual case, with the effect that an employee starts off with one process and finishes with a new process in place, as would have happened to Owen Paterson had he not resigned.

Owen Paterson’s resignation may have been the culmination of many months of anxiety and uncertainty over the allegations made against him. However, the 24-hour period of government induced chaos over the way in which they announced their review and the admission that they conflated the review with the Paterson case is likely to have been a last straw factor in his resignation. From an employment perspective had an employer acted in a similar way to the government, by using the Paterson case as collateral for the review, the risk of a successful constructive unfair dismissal claim would be high.

The impacts of the conduct review row will create political fodder for a few more weeks no doubt but the credibility of those deciding to deal with the review in the way they have has been undermined. Loss of leadership credibility in a workplace environment by not following fair, transparent, independent and consistent processes will create an employee relations disaster.

Rebecca Thornley-Gibson is partner at DMH Stallard

No comments yet