A reported drop in defamation cases was gleefully seized upon by the media, but the reality is less straightforward.

Unsurprisingly, the media were quick to report the apparent decline in defamation cases by a third over the last year. Two broadsheets reported that defamation claims had decreased from 86 to 63. Sighs of relief all-round for the in-house lawyers of Fleet Street.

But where did these figures come from? And how reliable were they? Inforrm, the highly respected media law blog, has reported that rather than being based on judicial statistics, they were taken from the number of reported cases on Westlaw and Lawtel.

It does appear that there is a decline in defamation cases against some sections of the media. There is also a likely explanation for this. The Defamation Act 2013, which came into effect in January 2014, introduced, among other amendments to libel law, the requirement that a claimant in a defamation case show they have suffered serious harm as a result of the article complained of. This was always intended to be a deterrent to all but the most aggrieved claimants, and it appears it is proving so.

It is hardly surprising that this new requirement, introduced to exclude what were perceived as trivial cases, has affected numbers. Defamation claims by commercial organisations have dropped even further. Thomson Reuters reported a drop of 45% in respect of these claims, from 31 to 17. It also reported that the drop was a result of the Defamation Act’s attempts to address libel tourism. It is difficult to verify whether these statistics or the analysis are correct. In my view, the UK’s attraction to libel tourists has been overstated in the past and is certainly further diminished following the act.

The act requires that businesses prove that the ‘serious harm’ had caused or was likely to cause financial loss. For a business to isolate why it has suffered a downturn and to show that this is attributable to a particular defamatory article was always going to prove difficult.

In most cases where the test is satisfied, the business also has to decide whether it is going to make a bad situation worse by making public in a defamation claim the fact that the business has declined.

But these media reports of the decline in defamation claims are in stark contrast to the judicial statistics, which indicate a rise in claims in 2013 of some 60%. The media were quick to report that the purported drop arose because of the high number of ‘trivial’ claims that had been issued in the past and, accordingly, the ‘serious harm’ test had helped prevent speculative claimants. The reality is likely to be less straightforward. Claimant libel lawyers have long argued that very few defamation claimants bring trivial claims.

Defendants had long struck out claimants that did not meet the necessary threshold of seriousness. On a more practical level, why would any claimant endure the cost and stress of a libel action except in the most serious of circumstances? Certainly, few firms would wish to act on a conditional fee agreement except in the case of a serious libel.

The rise in cases in 2013 appears to be primarily (and unsurprisingly) caused by the increase in claims involving social media, such as Twitter and Facebook. Whereas libel lawyers previously spent their time grappling with newspaper articles, most of the action is now in connection with damaging material posted online.

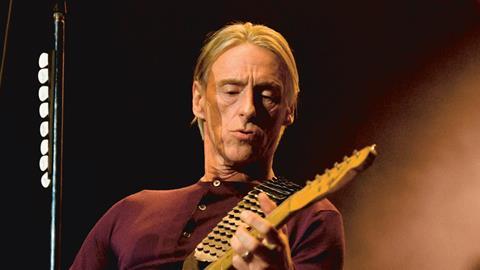

Another reason why the statistics concerning libel claims do not tell the whole story is that libel is but one of a number of weapons for claimants with complaints about publications. The continuing rise and significance of privacy claims has recently been confirmed by the Court of Appeal upholding the damages in the Paul Weller (pictured) case. The court was not prepared to interfere with the damages awarded against the Daily Mail for photographs taken by it and published of Weller’s children, despite the fact that the children were in a public place and the photographs were relatively innocuous.

The question of privacy damages is also being scrutinised by the Court of Appeal in the phone-hacking case of Gulati et al v MGN Ltd ([2015] EWHC 1482 (Ch)). If this decision is also in the claimants’ favour, future claimants will approach similar claims with high expectations.

There is also a significant increase in claims relying on the extended scope of the Data Protection Act (see, for example, Vidal-Hall [2015] EWCA Civ 311, bound for the Supreme Court). Likewise the growth of harassment cases, such as Brand & Anor v Szilvia (aka Sylvie) Berki [2014] EWHC 2979 (QB).

Accordingly, while it is correct to observe that the profile of defamation claims is changing and the new act would encourage a claimant to proceed cautiously, the overall picture is that this area of practice is as vibrant as it ever has been.

Sarah Webb is a partner in the privacy and media department of Payne Hicks Beach

No comments yet