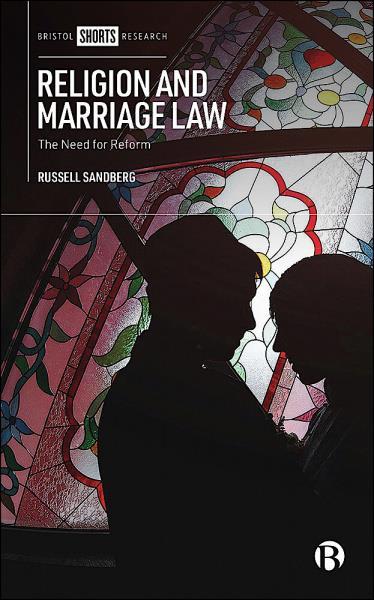

Religion and Marriage Law: The Need for Reform

Russell Sandberg

£40, Bristol University Press

★★★★✩

‘A wedding is not only an event of personal significance for the couple concerned,’ according to Eady J in R (On the Application of Harrison) v Secretary of State for Justice, ‘it has legal implications such that there is a wider public interest in preventing sham and forced marriages, in confirming that those who seek to marry are legally free to do so, and in ensuring there is certainty as to when a marriage has taken place.’ The Law Commission agrees, and later this year the commission will, it is hoped, publish its final report on weddings law reform.

In Harrison the issue was why the claimants – humanists from different parts of England – were not able to have a humanist wedding ceremony. The short answer lies in the Marriage Act 1949. Social attitudes have moved on considerably since 1949, but notwithstanding the introduction of same-sex marriages, the general legislative framework remains stuck with an anachronistic concept of when the state should recognise a valid marriage. In Harrison, the only factor that prevented Eady J from granting a declaration of incompatibility with the Human Rights Act was the government’s argument that reform was coming: avoiding piecemeal reform of a complex area of the law was a legitimate aim, pursued appropriately.

Russell Sandberg, a professor of Law at Cardiff University, has stepped into the debate with a clear and convincing analysis of the law as it currently is, the need for reform, and where, even if fully implemented, the commission’s proposals are by no means perfect.

Why does this topic matter? As Sandberg points out, we have an essentially secular concept of divorce – but what constitutes a valid marriage is laid down in the 1949 act. This means that marriage is defined by reference to an antiquated and overly complex legal framework, subject to piecemeal reform, but still no longer fit for purpose in the 21st century. Those definitions, as this work shows, can be seen to be indirectly discriminatory in respect of certain religious traditions. It could also be indirectly discriminatory for those who wish to celebrate marriage through non-religious belief. There will also be those who believe they have gone through a religiously valid ceremony, only to find that they are not married in the eyes of the law, and thus denied any protection in case of relationship breakdown or the death of a partner.

The book first gives a clear exposition of where the law is at present, both as regards opposite-sex marriage – whether religious or secular – and same-sex marriage.

The introduction of the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013 neatly illustrates the law’s complexities. In seeking to bolt on provisions permitting same-sex marriages where the underlying legislation was based on a religious, Christian, view of what marriage is, anomalies were inevitable.

Sandberg then goes on to discuss Akhter v Khan in the context of unregistered religious marriages, and whether criminalising those who solemnise religious weddings that fall outside the scope of the 1949 act would present a solution. Having then turned the spotlight on non-religious weddings, Sandberg also considers the commission’s proposals. The author concludes that the changes proposed would help mitigate some aspects of the law’s failings – but should not be seen as a magic bullet curing all its ills. In the latter regard more is needed, and Sandberg makes the case for exactly those reforms. Sandberg proposes an Intimate Adult Relationships Act to provide a fair, equal and modern law, covering both marriage and cohabitation. Taking an overview of how wedding law is applied in the other nations within the British Isles (and in Jersey and Guernsey), the author has drafted his own proposed legislation, filling the gap he sees in the commission’s work.

The work concludes by considering two further topics: what role the criminal law should play when it comes to discouraging abuses within unregistered marriages, and the need to reform cohabitation rights. The author convincingly puts the case that what is needed with regard to the former is clarity in distinguishing between a void marriage and a non-qualifying marriage, an issue the Court of Appeal in AG v Akhter felt was one for the legislature and not the courts. As regards cohabitation rights, both Scotland and Ireland have legislated for such rights, in 2006 and 2010 respectively (in Gow v Grant, Lady Hale gave express approval to the Scottish approach).

Sandberg is to be praised for his contribution to an important topic, not just in how he dissects the failings of the existing law but also in how he sees suitable paths for reform. In so doing, he shows how practitioners can benefit from the work of law faculties. Whether or not philosopher Søren Kierkegaard was right to say that ‘if you marry you will regret it; if you do not marry you will also regret it’, at least if our legislature was guided by Sandberg’s views then those regrets would not be the fault of the law.

Max D Winthrop is senior partner at Short Richardson & Forth, Newcastle upon Tyne

1 Reader's comment