Wetlands and International Environmental Law

Royal C. Gardner, Richard Caddell and Erin Okuno (editors)

£140, Edward Elgar Publishing

★★★★✩

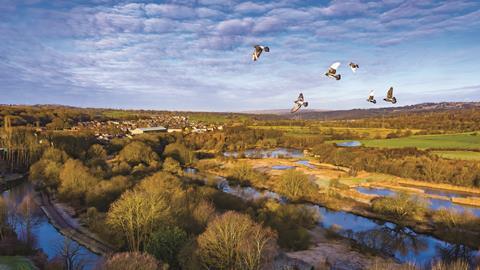

Many years ago, I carried out my GCSE geography fieldwork at Slimbridge Wetland Centre just outside Gloucester. The raucous squawking of visiting white-fronted geese stuck in my mind. Anyone who has spent a lazy afternoon watching the birds in such a spot will know the importance of the wetlands not just to our mental health and physical wellbeing but to biodiversity in the UK and internationally.

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance – something the book acknowledges few people may have heard of, this reviewer included – the book is split down the middle. The second half deals with legal aspects of the Convention such as interaction between other relevant conventions, the role of international law, and contextualisation of the Convention in the sphere of European nature conservation law generally. But it is the first part that is fascinating: an exhaustive exploration of change over 50 years, particularly in terms of its scope for (re)interpretation.

This is particularly so in relation to the social elements of the protections offered by the Convention: its acknowledgement of community impact, its contribution to community wellbeing, and the importance of community-led initiatives as part of wetlands management and conservation. In a moment where approaches to climate change and sustainability are on a knife edge, the book is a timely reminder that successful international legal endeavours to safeguard and preserve are possible without being unduly prescriptive, leaving room for advances in both science and social impact.

Perhaps this is typified by the changing interpretation of the definition of ‘wise use’, which, we are told, was originally intended to prevent irrational use of wetlands – in the legal sense of use incompatible with the Convention’s overall aims. The concept has been developed to include a proactive element: sustainable activity for wider stakeholder communities while preserving the wetland ecosystem (page 116). The debate is not over: discussion continues over whether this imports a conduct-based or an outcome-based obligation (essentially do those responsible for wetlands management or governance need to try their best not to ruin it or to achieve a particular impact). A proffered alternative is characterising ‘wise use’ as a due skill and care-type commitment.

This is just an example of the interesting fluidity of international co-operation, well captured in this important book and its investigation of how critical natural infrastructure can be managed for future generations.

Tom Proverbs-Garbett is the director of TrustPoint Governance

No comments yet