Natural Law and Modern Society

Sean Coyle

£110, Oxford University Press

★★★✩✩

Synderesis is a handy Greek word, meaning the spontaneous capacity to comprehend certain acts as indubitably wrong or indubitably right. Very broadly, natural law theory posits that, as humans, we have that capacity and could and should use it. Casting the human as a moral force in defining the law starts with Greek thought, personified by Aristotle, and is also represented by the work of Jewish writers from the time of Philo of Alexandria.

Islamic scholar Avicenna reintroduced natural law theories into the European consciousness, with such theories crystallised in the work of St Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274). Tucked away in Aquinas’s monumental Summa Theologica, questions 90–108 of the Prima Secundae form a mini-thesis on law. From this work sprung the modern concept of natural law.

So what exactly is natural law? To Aquinas, as he tells us in the Summa, law itself was nothing less than an ordinance of reason for the common good. Natural law bound only rational creatures – humankind – because it needed a rational and free mind to agree to its precepts. As natural law emanated from the rational mind of God it was inherently good. But mankind did not need divine revelation to follow it. This was achieved through the powers of right thinking.

The learning that explains natural law seeks to provoke the questions that consider and define the main qualities of jurisprudence. These, according to Coyle, include the relationship of legal duties to moral truths, and whether one can discover the meaning and validity of those truths.

Natural law has always had its detractors. Some theologians considered that if human action could be morally right, without the need for divine revelation, you dethrone God. With the Reformation, there came a curious coupling of calls for religious freedom with strict predestinarianism (the idea that, as God by definition is all-knowing, then He has already decided who is damned and who is saved and that free will is an illusion). ‘Scholastic’ became, for a time, a dirty word in some circles, but Aquinas’s ideas remained central to the worldview of Catholic Europe.

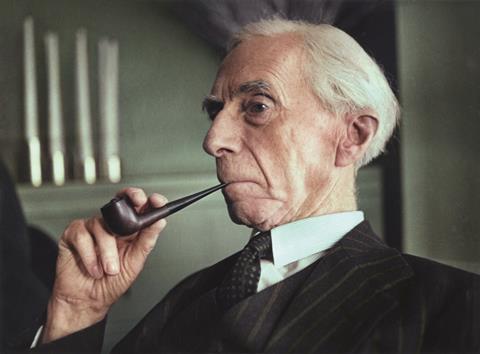

Despite religious factionalism, natural law was revived in the 17th century. Thinkers like Suarez, Grotius and the Middle Temple’s own Richard Hooker, from different sides of the religious divide, introduced a second period of scholastic thinking. That did not stop a further attack on natural law theory. This time, instead of protestant theologians who were nervous of any theory that hinted at morality without revelation, the need to remove God from any philosophical system played its part. There were those who saw natural law as flawed by ‘deductivism’ – the idea that from a few clear principles you can rationally deduce all areas of the rules that are to govern society. Legal positivism (briefly, the idea that law is just whatever state power cares to define as law, regardless of any moral content) saw no room for metaphysical concepts like objective truth. Such concepts could exist only, at best, as a series of personal and relative truths. And perhaps most famously, Bertrand Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy condemned Aquinas as a second-rate philosopher.

Coyle makes a convincing case that natural law’s inherent ethical basis is needed now more than ever, given we may be living through a post-truth age. Coyle’s work is not a simple description of natural law theory, still less a biography of Aquinas. Instead, Coyle makes a rational division of the book into three parts. Part One explains what natural law is and how it seeks human good; Part Two further explores ethics and morality; and Part Three dives deeper into legal, political and moral authority, including the question of whether unjust law can be said to be in any real sense ‘law’. While each part of the book could be treated as a standalone work, taken together all three parts give the reader a deeper insight into natural law theories than simply focusing on individual elements.

As far as jurisprudence is concerned, many might echo Lord Denning’s view that the subject is just ‘ideologies, legal norms, and basic norms, “ought” and “is” realism and behaviourism, and goodness knows what else’. Perhaps natural law’s greatest strength is that it substitutes ethics for ‘isms’.

I would have liked the author to have applied natural law theories to the ethical questions that are thrown up by our courts and tribunals, to show that natural law – unlike legal positivism – is not simply an analytical tool. If natural law precepts have a role to play, then I would have liked the author to demonstrate how its precepts could have confirmed or disagreed with recent high-profile decisions in areas such as religious expression or the (im)mutability of gender. Legislation increasingly reduces judges to the status of interpreters of texts or mere literary critics of opposing arguments. Natural law, however, provides a basis for justice in decision-making.

Ultimately, natural law’s recognition that there is validity in the idea of the good is its greatest strength. Coyle’s work will be an indispensable source for those who want to look beyond positivism and other systems that deny the possibility of objective truth in understanding law.

Max D Winthrop is a partner at Sintons LLP in Newcastle

1 Reader's comment