Costs management is one way in which Sir Rupert Jackson proposed to control the escalation of costs.

He described its significance in his final report: ‘Costs management is an adjunct to case management, whereby the court, with input from the parties, actively attempts to control the costs of cases before it. Effective costs management has the potential to lead to the saving of costs (and time) in litigation’ (Review of Civil Litigation Costs: Final Report (2010) paragraph 6.10-6.11).

Costs management now applies to all part 7 claims below £10m. The relevant rules can be found in Civil Procedure Rules 3.12 to 3.18 and Practice Direction 3E on Costs Management. The recent case of GSK Project Management Ltd (in liquidation) v QPR Holdings Ltd [2015] EWHC 2274 (TCC) illustrates some of the difficulties parties may face when seeking approval of their costs budgets.

The rules

Under the rules, all parties (except litigants in person) must file and exchange costs budgets in which they must provide an estimate of the costs that are likely to be incurred at each stage in the litigation process (CPR 3.13). The budgets must be filed by the date stated in the notice of proposed allocation or, if no date is specified, seven clear days before the first case management conference (CPR 3.13). The budget must be verified by a statement of truth (PD 3E, paragraph 6).

The court has the discretion to make a costs management order, in which it will record the extent to which the budgets are agreed between the parties, or (to the extent not agreed) record the court’s approval of a budget, if necessary after making appropriate revisions (CPR 3.15). Where costs budgets have been filed and exchanged, the court will make a costs management order ‘unless it is satisfied that the litigation can be conducted justly and at proportionate cost in accordance with the overriding objective without such an order being made’ (CPR 3.15(2)).

GSK Project Management Ltd

The claimant company, now in liquidation, was formed to carry out works at Queens Park Rangers Football Club’s Loftus Road ground. The defendant is the parent company of the group that includes the operator of the football club and occupier of the ground. The claimant claimed £805,675 from the defendant for work carried out at the ground. The defendant counterclaimed on the basis that some of the works were defective. The parties agreed on a four-day trial.

The claim form was eventually issued in March 2012, but instead of following the claimant’s solicitors’ instructions, the Salford Business Centre served the claim form itself by sending it directly to the defendant by first-class post.

The defendant’s solicitors wrote to the claimant’s solicitors asking them to note their interest, to which the claimant’s solicitors replied that the form has been served in error and that it had been referred back to the Central London County Court and put right, and that it would be served within four months of issue. The defendant’s solicitors took that statement at face value and treated the service as ineffective.

The claimant’s solicitor believed the judge, Mr Justice Stuart-Smith, was required to consider the parties’ costs budgets. The claimant’s cost budget produced for the first case management conference on 24 July 2015 was in the overall sum of £824,038 and stated that more than £310,000 had already been spent. The overall estimate therefore exceeded the sum at stake (exclusive of interest), while the sums which were alleged to have been incurred amounted to nearly 40% of the sum at stake. By comparison, the defendant’s cost budget was in the total sum of £455,554.

Stuart-Smith J adopted the approach of Coulson J in CIP Properties (AIPT) Ltd v Galliford Try Infrastructure Ltd [2015] EWHC 481 (TCC). On the facts of CIP, Coulson J considered the following when dealing with the claimant’s costs budget:

i) The proportionality of the claimant’s costs budget;

ii) The reasonableness of the claimant’s costs budget;

iii) Summary of options; and

iv) Conclusions on the available options.

Proportionality of the claimant’s costs budget

Stuart-Smith J began by stating that a case would have to be wholly exceptional to render a costs budget of £824,000 proportional for the recovery of £805,000 plus interest. This case was not exceptional in any material respect. The contract was agreed and the issues to be decided were clear. Further, the case would involve a handful of witnesses and require only four days of trial. On the issue of proportionality, good reason would need to be shown to justify more than about half of the £824,000 being claimed.

Reasonableness of the claimant’s costs budget

Counsel for the defendant submitted that the correct approach when assessing one party’s costs budget is to take the other party’s costs budget as a starting point. The judge disagreed, because different parties to litigation have different roles and responsibilities which are likely to distort one party’s costs when compared with those of another.

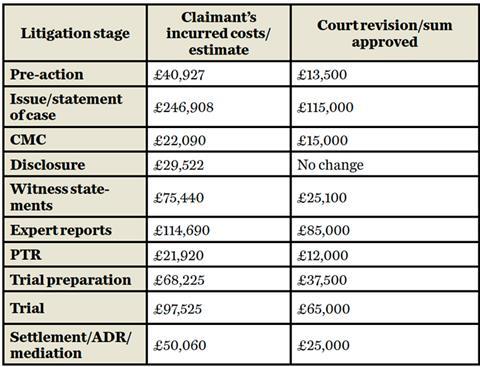

He accepted that the court should have regard to the other party’s costs budget because it may provide useful indicators about necessary resourcing of the litigation. Stuart-Smith J then turned to the various heads of costs in the claimant’s cost budget and made the following adjustments (see table, below) which, in his view, were reasonable and proportionate costs.

The judge then noted the available options outlined by Coulson J in CIP. These included:

i) Option 1A: ordering a new budget;

ii) Option 1B: declining to approve the claimant’s costs budget;

iii) Option 2: setting budget figures; and

iv) Option 3: refusing to allow any further costs.

In CIP, Coulson J settled on option 2 in a case where the claimants said that they had already incurred the same amount of costs as he assessed as being reasonable and proportionate for the action as a whole. In the present case, Stuart-Smith J adopted option 2 as the most appropriate method of resolving the issues on costs.

The judge also made clear that the provision in CPR 3E PD 7.4 – that the court may not approve costs incurred before the date of any budget but may take those costs into account when considering the reasonableness and proportionality of all subsequent costs – did not make specific provision for the situation where, as in the present case, taking the incurred costs into account reveals a disproportionate level of expenditure with no consequential benefit being reflected in the estimate of future costs.

He agreed with Coulson J in CIP that ‘… there is no prohibition against saying what the court would have approved if presented with an estimate for future costs rather than the fait-accompli of incurred costs’.

He went on to explain that the summary nature of the costs budgeting procedure meant ‘… that the court may either overestimate or underestimate the future expenditure of costs that will reasonably and proportionately be required. If a lower level of costs than estimated turns out to be reasonable and proportionate, the other party’s protection lies in assessment: the costs judge can disallow costs even though the approved budget has not been exceeded.

'If a higher level of costs is in fact required in order to run the litigation reasonably and proportionately, the affected party has the leeway afforded by CPR 3E PD 2.6, which requires a party to revise its budget in respect of future costs if significant developments in the litigation warrant such revisions, and CPR 3.18, which allows the court when assessing costs on the standard basis to depart from the approved or agreed budget if satisfied there is good reason to do so’.

Finally, the claimant argument that the nature of the litigation was ‘combative’ and therefore meant substantial costs were incurred was dismissed. Stuart-Smith J referred to the recent observations of Edwards-Stuart J in Gotch v Enelco Ltd [2015] EWHC 1802 (TCC), where he said: ‘44. It is therefore time to say, in the clearest terms, that parties and their solicitors can no longer conduct litigation in a manner which does not keep the proportionality of the costs being incurred at the forefront of their minds at all times.

‘45. It is no longer acceptable – if it ever was – for the parties to pursue issues or applications that have no real impact on the issues that are central to the dispute. Further, it is no longer acceptable for solicitors to carry on a war of attrition by correspondence, whether instructed to do so or not; it is the parties who are the subject of the duty in CPR 1.3, not merely their solicitors.

‘46. […]

‘47. Whilst English law is an adversarial process, that goes to the issues in the case: not to every aspect of the procedure. Parties to litigation, in the TCC at least, are expected to conduct that litigation in the manner that is most expeditious and economical. Bringing the right issues to trial in the most economical fashion, and taking steps to ensure that the costs are kept at a level that is proportionate to what is at stake, is to be at the heart of the process.

‘48. Unreasonableness, intransigence and the taking of every point must in my view now be regarded as unacceptable, because conducting litigation in that way flies in the face of the overriding objective as it is now formulated. These habits must disappear from the landscape of litigation in the TCC. If they do not, offending litigants must expect to bear the costs.

‘49. If access to justice is to have any real meaning, then the aim of keeping costs to the reasonable minimum must become paramount. Procedural squabbles must be banished and a culture of cooperative conduct introduced in their place. This will not prevent contentious issues from being tried fairly: on the contrary it should promote it.’

This case is yet another important reminder for litigating parties to tread with caution when preparing their costs budgets. Where costs are considered to be unreasonable and disproportionate, judges will not hesitate in revising those costs down as illustrated by this case.

As Edwards-Stuart J made clear in Gotch, the culture of litigation has changed from a purely adversarial process to one which is governed by the overriding objective of dealing with cases justly and at proportionate cost.

Masood Ahmed, University of Leicester

No comments yet