The latest on wasted costs orders, asylum and identification procedures.

In a case involving a wasted costs order (In the matter of a wasted costs order against Joseph Hill & Company [2013] EWCA Crim 775), the Court of Appeal has identified a widespread misunderstanding within the profession about the purpose of an alibi notice.

The solicitors had, as was common practice, delayed service of the notice because they did not have a supporting witness statement from the alibi witness. The court pointed out that such delay could not be justified because the purpose of the notice was only to state the defendant’s belief as to his alibi and was not a statement of fact. As the defendant will be able to identify his belief as to his whereabouts immediately, there can be no justification for delay. However, nor may the defendant then be cross-examined on the basis that the alibi was factually incorrect if his belief was genuine. Because the correct position was so widely misunderstood, the court allowed the appeal against the wasted costs order but indicated that orders would be permitted if trials were delayed now that the true purpose was understood.

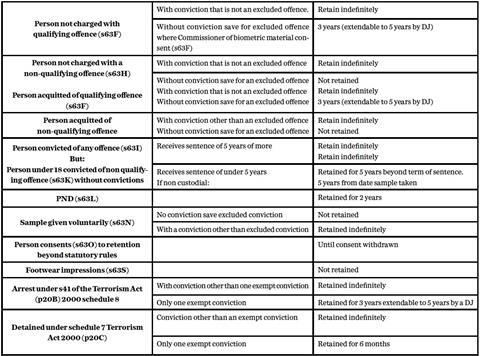

Retention of samples after conclusion of current case (section 63E of PACE)

The position following the implementation of the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012, inserting sections into the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, is summarised in the box, above right. It applies to DNA from 31 October and to fingerprints from 31 January 2014. However, all samples will be subject to a speculative search before destruction.

Identification procedures

In R v Cole [2013] EWCA Crim 1149, there had been a clear breach of code D of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) when the police failed to disclose to a solicitor a note with a further description of the suspect.

However, the appeal (on a Criminal Cases Review Commission reference) was refused as it was unrealistic to suggest that the suspect would have been advised to refuse to take part in the identification procedure.

The case confirms that whatever failure may be found, the client should be allowed, under recorded protest, to take part rather than risk a worse identification procedure.

Causing death while uninsured, unlicensed or disqualified (section 3ZB of the RTA 1988)

The Supreme Court has settled the law in relation to this offence in R v Hughes [2013] UKSC 56. The driving must be a cause of the death. Where the driver is faultless and the total responsibility for his death lies with the deceased, no offence is committed under these provisions. The court would also examine cases where there was a deliberate intervening act such as the deceased committing suicide. The argument that ‘but for’ the presence of the vehicle on the road the death would not have occurred is not to be used. To be guilty, the driving of the defendant must contribute in more than a minimal way to the death.

Defences

R v Morris [2013] EWCA Crim 436 has importantly clarified the meaning of the defence in section 3 of the Criminal Law Act 1987 which is available in relation to all crimes. Here, a cab driver mistakenly but honestly believed that his passengers had made off without paying their fare and drove dangerously to arrest them under section 24A of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 This was held to be a valid defence.

Defence under section 31 of the Asylum and Immigration Act 1999

In R v Matete and others [2013] EWCA Crim 1372, the Court of Appeal has pointed out that there is an obligation on those representing defendants charged with an offence of possession of an identity document with improper intention to advise them of a possible section 31 defence.

A simplified version of the main elements of this defence is:

1. The defendant must normally provide sufficient evidence in support of his claim to refugee status.

2. It then falls to a defendant to prove on the balance of probabilities that:

a) he did not stop in any country in transit to the UK for more than a short stopover;

b) he presented himself to the authorities in the UK ‘without delay’;

c) he had good cause for his illegal entry or presence in the UK; and

d) he made a claim for asylum as soon as was reasonably practicable after his arrival in the UK.

3. The requirement that the claim for asylum must be made as soon as was reasonably practicable does not necessarily mean at the earliest possible moment.

4. The fact a refugee stopped in a third country in transit is not necessarily fatal and may be explicable. The main touchstones by which exclusion from protection should be judged are: the length of the stay in the intermediate country; the reasons for delaying there; and whether or not the refugee sought or found protection from the persecution from which he or she was seeking to escape. Thus, a ‘short stop-over’ can in fact be quite lengthy.

5. The requirement that the refugee demonstrates ‘good cause’ for his illegal entry or presence in the UK will be satisfied by him showing he was reasonably travelling on false papers.

Anthony Edwards, TV Edwards

No comments yet