The Woolf reforms have a chequered history, reports Katharine Freeland. Civil procedure still lacks a compelling vision

The low down

As master of the rolls, Lord Woolf painted a picture of a civil justice system in which warring parties were prompted to review the strength of their position early, encouraged to use mediation and induced to settle early. By cutting the length of disputes, commerce would be served because disputes would be shorter. This would cut the cost of falling out and costs would in any case be better managed. The ‘Woolf Reforms’ were brought in by the Civil Procedure Act 1997, in force in England and Wales from April 1999. Critics say the reality proved to be higher upfront costs for cases that might otherwise have settled with less work done. The response has been to overpaint Woolf’s work with further layers of reform. So how well is civil justice now being served?

The task handed to the master of the rolls by lord chancellor James Mackay in 1994 was simple enough to express. Lord Woolf was to set out proposals to consolidate the existing rules of civil procedure in such a way as to make justice cheaper, quicker and easier to understand for non-lawyers.

Woolf’s solution was anything but simple, for it brought in the concept of ‘case management’. This shifted the day-to-day handling of civil litigation from litigants to judges. Empowered to use their discretion, judges could set early trial dates or order case management conferences to narrow issues and set out the framework and timetable of each case.

The move to judicial-led case management was a practical step to support the overriding objective of the Civil Procedure Rules (CPR). Civil litigation should be conducted fairly and justly – ensuring that parties are on an equal footing – and in a proportionate and cost-effective way.

Digital revolution

Experience of case management under the CPR varies wildly, depending on the individual judge and precedents of each court. The scope of the CPR is vast, covering practice and procedure in the civil divisions of the Court of Appeal, the High Court and county courts.

Areas such as immigration, tax and employment have their own tribunals. CPR will apply though if cases reach the appeal court and in applications for judicial review, which must follow the relevant pre-action protocol.

Another relevant factor is modernisation. The court system of England and Wales is undergoing a wide-reaching programme of digital transformation. HM Courts & Tribunals Service (HMCTS) has digitalised civil court services for smaller, less complex cases, introducing online case management, digital submissions and remote hearings.

‘Recent civil procedure reforms have focused on increasing efficiency, effectiveness and access to justice, notably through digitalisation and technology and the integration of ADR,’ says Gazette author Masood Ahmed, associate professor of law at the University of Leicester. ‘The Online Civil Money Claims (OCMC) service is a good example, designed with litigants in person in mind with embedded ADR procedures. This reduces time for court directions and improves the user experience.’

The OCMC operated a pilot of automatic referral to mediation for certain claims. An hour-long session was available to participants over the phone to encourage resolution without proceeding to trial.

As well as the OCMC – which covers money claims up to £25,000 – county court damages claims, low-value road traffic accident (RTA) personal injury claims and repossession claims moved online. Video technology has been installed in many courtrooms under the HMCTS reform programme, which concluded in March 2025, and e-filing has been made mandatory in the appeal court (Civil Division).

Ahmed adds: ‘AI and other advanced technologies can be used to signpost next steps and streamline processes, such as the uploading of evidence, without replacing judicial discretion.’

Although practitioners welcome how digitalisation has smoothed the way in certain corners of the civil court system, many obstacles remain. Delay, escalating costs and unpredictability persist, particularly in the county courts.

Congestion and delay at the lower levels

The cross-party Justice Committee’s July report into the functioning of county courts was damning. Yet in October, ministers rejected its recommendation to undertake a ‘root-and-branch’ review to address systemic delays and entrenched inefficiencies across these courts. The report found that ‘the decade-long digital reform programme has fallen well short of its ambition, leaving a myriad of incompatible systems and outdated paper-based processes’.

Thoroughly underwhelmed by such a record, the committee described the civil justice system as the ‘Cinderella service’, pointing out that, unlike the sentencing system and the criminal courts, it has not had the advantage of a detailed review.

The HMCTS overhaul closed ‘underused’ buildings and sites to save money, as well as cutting service staff on the ground. Lawyers report that the remaining county courts are dilapidated and ill-equipped, and delays in listing cases extensive.

Barrister Andrew Hogan is a costs and litigation funding specialist at Hailsham Chambers, who regularly appears in the county courts, High Court and Court of Appeal. ‘It is noticeable in recent years that the practical administration of the county courts has deteriorated due to centralisation and the loss of institutional knowledge,’ he says. ‘You used to be able to liaise with a diary manager at each court to arrange a date for a hearing and it worked very effectively. Now emails are left unanswered and there is little accountability.’

The higher courts fare better, with lawyers instructed on high-value multi-track cases finding that new online court filing systems and the requirement for virtual document bundles are making a noticeable difference in practice, increasing speed and efficiency.

‘Although law firms vary in their approach, AI is also easing the load for disclosure review, document analysis and early-stage investigations in what used to be document-heavy cases,’ says one litigator, who specialises in complex commercial disputes.

Judges and the court system are still adapting to the use of technology, though, as are some practitioners. ‘There is a lag in adoption and understanding in the courts compared to the private sector,’ they say. ‘A disconnect is sometimes evident between judicial expectations and the practicalities faced by solicitors, particularly regarding what is possible from technology within a certain timeframe.’

Solicitors working at this level do, however, praise the customary flexibility in case management that allows practitioners and judges to work together to replicate successful strategies from past cases, rather than rigid adherence to written-down rules. ADR is also increasingly prevalent, with judges taking a more active role in encouraging settlement.

Case management: what next?

The Civil Justice Council (CJC)’s Pre-Action Protocol Review final reports were released in August 2023 and November 2024.

A fundamental recommendation was the mandatory obligation for parties to engage in pre-action ADR, whether mediation, neutral evaluation or a straightforward meeting. Parties who comply would then be exempt from any automatic requirement to do so after proceedings are issued. The thinking was that such an exemption would avoid low-value disputes already subjected to a dispute resolution process from repeating ADR.

Other CJC suggestions included the introduction of a new General PAP to replace the existing Practice Direction on Pre-Action Conduct, which would cover disputes that fall outside specific PAPs. The new PAP would require early information exchange, engagement with a dispute resolution procedure, and a ‘stocktake’ process to narrow issues if a settlement is not reached. The CJC’s two-part report also promoted the development of online portals that are user-friendly for litigants in person and linked to the court process.

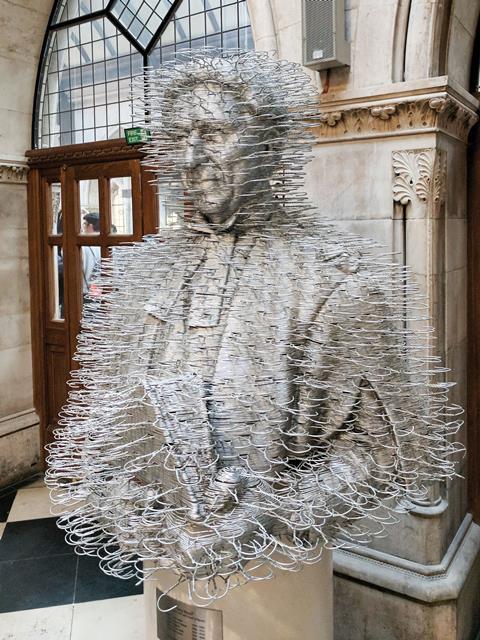

‘Linking pre-action protocols to the online court process is critical to avoid fragmentation and to build a holistic digital justice system,’ says professor Masood Ahmed (pictured).

The report is now with the Civil Procedure Rule Committee and the Online Procedure Rule Committee for review, with no existing timetable for implementation.

Mandating ADR

Although consideration of ADR was fundamental to the Woolf Reforms, it was not mandatory. Instead, the focus rested on cost penalties that the judge can impose on parties for failure to engage in ADR, an outcome that might seem a distant threat at the launch of a claim.

There are other cost deterrents to court action. ‘The cost of issuing a claim [5% of claim value, capped at £10,000] acts as a disincentive and is a spur to pre-action mediation,’ says Roger Levitt, a business and property mediator.

ADR featured in Churchill v Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council [2023], in which the Court of Appeal determined that the court could compel unwilling parties to engage in ADR without this undermining their Article 6 right to a fair trial under the European Convention on Human Rights.

Following the ruling, parts of the CPR were amended to allow the court to expressly order ADR and this was made explicit as part of the overriding objective. After Churchill, the courts can order parties to engage with ADR even if they have already been through the process at pre-action stage.

Churchill was no one-off. In Heyes v Holt [2024], the parties had attempted mediation before issuing proceedings but failed to reach agreement. HHJ Matthews, sitting as a judge of the High Court, ordered a stay of proceedings to enable the parties to engage in a second mediation. In Francis v Pearson [2024], HHJ Lewis, while not making an ADR order, ‘strongly recommended’ that the parties engage with a second mediation.

‘It may not be enough that the parties have engaged with ADR at the pre-action stage,’ says Ahmed. ‘These recent cases show that parties can be ordered to engage in a further round of ADR if the court considers it appropriate.’

The first compulsory mediation order was granted to the claimant, owner of the Superdry brand, in Superdry in DKH Retail v City Football Group Ltd [2024]. It was a trade mark dispute, with Miles J mindful that the parties had already run up costs of ‘hundreds of thousands of pounds’ and that a ‘short sharp mediation’ would help to resolve the vexatious points in dispute.

In Elphicke v Times Media [2024], a case concerning costs assessment, Master McCloud chose to make an ADR order of her own, rather than reacting to an ADR application order from the parties. ‘This proactive judicial approach should be encouraged and promoted,’ says Ahmed. ‘Particularly as the master reinforced her ADR order with reference to the court’s powers to penalise any party in costs for failing to comply with her order.’

An advocate for ‘judicial activism’ in ADR, Ahmed also points out that Elphicke was the first decision in which a senior judge mandated ADR in costs assessment proceedings on the grounds that further proceedings would only escalate costs and drain the courts’ resources.

Historically, civil courts have been reluctant to make ADR orders of their own or conduct ADR procedures themselves, although they have the powers to do so. Ahmed says: ‘This reticence contrasts with other courts, such as employment tribunals, where judges regularly take part in ADR processes.’

In her judgment, McCloud also referenced the ‘congested’ state of the court system as a compelling driver for using ADR to wrap up the case as quickly as possible – providing another good reason for mandating ADR from the outset.

‘The courts are increasingly unable to handle their caseload, leading to more reliance on ADR as an outlet,’ says Hogan.

Cultural shift required

'The perception that requesting mediation signals weakness has diminished'

Kelly Stricklin-Coutinho, 39 Essex Chambers

The mandating of ADR in the overriding objective is filtering into how lawyers approach case strategy. Although frustrations exist in some legal circles over an older generation of litigators stuck in the traditional adversarial mindset, the expectation is that those who have grown up with ADR as part of their practice will embrace it even more tightly.

Kelly Stricklin-Coutinho is a dispute resolution specialist at 39 Essex Chambers and chair of the Civil Mediation Council (CMC). ‘The perception that requesting mediation signals weakness has diminished, as the overriding objective now requires the parties to think about ADR such as mediation,’ she says. Therefore, parties who refuse to consider ADR are likely to be seen as not using all the tools available to them, leading to a cultural shift in how civil litigation is conducted.

But it is not just lawyers that need to shift their thinking. Ahmed argues that judges need to go further in their understanding of ADR when managing cases, changing the perception that ADR only refers to mediation.

‘Policymakers and the courts have failed to promote the full range of non-adjudicative ADR procedures that include conciliation, early neutral evaluation and negotiation, placing disproportionate emphasis on mediation,’ he says. ‘This undermines the court’s role in ensuring that it orders the most appropriate ADR procedure for the circumstances of the parties.’

Singapore should be an inspiration, some argue. A common law system rooted in English law, the jurisdiction role-models an effective civil justice system which recognises many different dispute resolution methods. The emphasis is on the judiciary finding the most appropriate method for the dispute at hand.

Some industry sectors, such as procurement, are less accustomed to ADR than others, such as tax or employment, which have tribunals with ADR built into their processes. Since 2023, mandatory ADR, called a dispute resolution appointment, permits judges dealing with complex claims in employment tribunals to require parties to participate in a process similar to early neutral evaluation, where a judge not connected with the case gives the parties a non-binding opinion on their prospects in the claim.

'There is a lack of vision for the future of civil procedure; no clear direction or objectives exist for the next five to 10 years'

Andrew Hogan, Hailsham Chambers

‘Proactive case management by judges may be beneficial in those areas where considering ADR is not yet a reflex,’ says Stricklin-Coutinho. She points out that the overriding objective applies to cases at every stage of the court process, affecting cases with both legally sophisticated parties and litigants in person.

Stricklin-Coutinho says: ‘Mediators are well placed to guide less experienced parties through the process, and dealing with imbalances of power is already part of their training.’

Parties unfamiliar with ADR can worry that it will be used as a stalling tactic to delay justice. However, Kelly reports that mediations can be organised at short notice. Courts typically set short deadlines and mediation costs are generally proportionate. ‘Preparation for mediation often overlaps with litigation preparation and even if the parties do not settle, mediation can narrow the issues between the parties or leave them better informed about the case they’re facing, so multiple mediation is still efficient and rarely a waste,’ she says.

Assessment of whether progress in CPR case management outweighs failure is a subjective one, dependent on the judge, court and the willingness of counsel to embrace developments, from digitalisation to mandatory ADR. For some, the constant tinkering around the edges of the CPR, including changes to case management, misses the point.

‘There is a lack of vision for the future of civil justice; no clear direction or objectives exist for the next five to 10 years,’ says Hogan. ‘ADR should be promoted as an appealing option to reduce backlogs, yes, but what is also important is empowering frontline court staff rather than top-down reforms, as practical local knowledge is essential for efficient court operation.’

Katharine Freeland is a freelance journalist

1 Reader's comment