Perhaps the defining ethical tension for in-house solicitors, as for all professionals, is between duties to the client and duties to the public interest. Nowhere is this tension felt more keenly than in cases of whistleblowing.

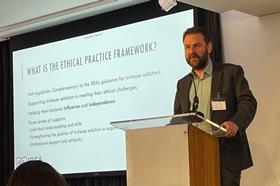

The Law Society’s ethical practice framework for in-house solicitors, which was launched in its second iteration following consultation on 27 October 2025, highlights whistleblowing as a key area of ethical complexity.

In response to requests from the profession for more targeted support, the framework now includes new guidance and model policy materials developed in partnership with Protect, the whistleblowing charity.

Ethical integrity in action

Why is whistleblowing so important? Simply put, it is one of the clearest expressions of ethical integrity in action: a willingness to raise concerns when something serious is going wrong. And it is a key element in the public’s defence against corporate misconduct. But it is also one of the most personally and professionally risky actions an in-house solicitor can take.

Unlike their private practice counterparts, in-house solicitors are embedded in the very organisations whose wrongdoing they may be concerned about. They are salaried employees, often working closely with senior colleagues whose decisions they may be required to challenge. Loyalty, trust and collegiality can be difficult to square with the need to blow the whistle.

In the research which informed the development of the framework, I spoke to solicitors who had become whistleblowers, both internally and externally. Taking this step is rarely, if ever, easy and I was struck many times by the courage it requires.

Read more

Whistleblowers can be vulnerable in multiple ways: to unemployment and the financial uncertainty that entails, to retaliatory legal action and to regulatory censure if they are seen to have breached a duty of confidentiality in coming forward.

There is a case to be made that protections for solicitors who are whistleblowers should be improved, particularly where their duty to raise concerns appears to conflict with their duties to their client under legal professional privilege (LPP). There is also, however, a need for greater clarity about the existing law and about currently available professional support for whistleblowers.

This is where the new resources from Protect come in. Their guidance –now included in the framework – offers a clear, practical roadmap for solicitors considering whether and how to raise concerns. It sets out key questions, such as:

- Is my concern about a public interest issue?

- Do I have a duty to raise the concern?

- Might raising it place me in breach of confidentiality or LPP?

- Should I report internally or externally?

- What are the personal and professional risks of doing so, and what protections exist?

The guidance explains the nuances of whistleblowing law, including the criteria for making a ‘qualifying disclosure’ and the protections available under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998.

It signposts solicitors to sources of advice – including the Solicitors Regulation Authority’s professional ethics helpline and Protect’s confidential support line – and urges them to seek advice early, especially where privilege or regulatory duties are at stake.

To complement the guidance, the new version of the framework also includes a model whistleblowing policy template. This is intended for use by in-house legal teams in engaging with their organisations.

As our research highlighted, having a clear, well-communicated whistleblowing policy, trusted by staff and understood by managers, can make an enormous difference to whether concerns are raised and addressed appropriately.

In-house lawyers are often well-placed to advocate for the development or improvement of such policies, but they need tools to support them. The template is adaptable to a range of organisational contexts, including private companies, public bodies and charities, and can be tailored to reflect internal reporting structures.

Open organisational culture

More broadly, the ethical practice framework encourages in-house solicitors to take an active role in promoting open cultures within their organisations. This includes creating conditions in which legal advice can be given without fear or favour, and where staff at all levels feel empowered to raise concerns.

This is not about elevating solicitors above others, but about recognising that they have a distinctive role to play in upholding legal and ethical standards.

Solicitors are well-placed to help make the organisation a place where whistleblowing is rarely necessary, but also to help ensure channels and support are in place for when it is necessary.

Ultimately, whistleblowing is a key element in a broader culture of ethical accountability. The best organisations do not wait for a crisis to take it seriously. They embed accountability into their governance structures, build trust in reporting mechanisms and ensure that those who raise concerns are supported, not punished. In-house solicitors are a vital part of this picture.

Dr Jim Baxter, IDEA The Ethics Centre, University of Leeds

2 Readers' comments