Andrew Parsons, a solicitor and partner with Womble Bond Dickinson, faces questions on his role in defending the Post Office during the Horizon scandal

4pm: And with that we wrap up early for the day. But the ordeal for Parsons is by no means over. Blake says he has another hour's worth of questions, and then representatives of the sub-postmasters have asked for a collective hour and a half to question the witness.

We'll be back tomorrow with all the latest.

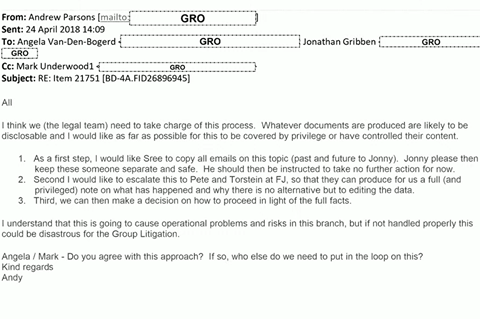

3.55pm: A fresh problem arose in 2018 when it emerged that remote access had been possible at a branch. After several internal emails, Parsons intervened to tell senior executives that the legal team 'need to take charge of this process' (see below). He pointed out that documents are likely to be disclosable and needed to be 'covered by privilege'.

Blake says this takes us right back to the first issue this morning, where Parsons is advising the Post Office to 'blanket this in privilege'.

Parsons says each decision was context-specific and that the Post Office was in the middle of a group litigation when it needed control of what was being disclosed.

'Post Office was entitled to avail itself of legal privilege,' he adds.

3.35pm: Parsons, who is speaking much quieter than at the start of the day, is shown his email accompanying a draft email that was going to be sent to Freeths. This would make some admissions that there was indeed remote access, despite what had been said previously.

Parsons expressed his hope that the Post Office had found a choice of word that ‘avoids having to overly throw [Fujitsu] to the wolves’. He also said the Post Office had ‘toned down the admissions of making incorrect statements’.

These internal discussions included Mark Davies, Post Office head of PR, who Parsons says would ‘occasionally get involved in legal issues’.

3.15pm: Blake rattles on to the issue of remote access. Parsons was included in an email chain where comms chief Melanie Corfield and compliance director Mark Underwood discussed new questions that were arising in 2015 about Fujitsu being able to access branch accounts without sub-postmasters knowing.

Underwood suggested the Post Office ‘treat any questions about RA with the contempt they deserve – why on earth would PO have a secret bunker in [Fujitsu HQ] Bracknell accessing sub-postmasters’ accounts?’ Corfield joined in, adding: ‘I completely agree re showing contempt about the allegations on this subject.’

Parsons tells the inquiry these responses were ‘probably too strong’, but the email chain shows he also responded, sharing his view that any sign that remote access was possible would be a ‘red rag’ to critics. He now says he wishes he had pushed harder to know what remote access there was.

We take a short break.

3.05pm: Blake asks whether the mediation scheme was doomed to fail from the start. Parsons says no and that the Post Office went into it in good faith. He says the relationship with Second Sight could have been more collaborative but concludes that mediation did a lot of good.

Blake asks whether he personally should have taken a less adversarial approach to Second Sight. 'Yes, with hindsight,' says Parsons. 'There were some points where we were fair in criticising Second Sight but some where we were too adversarial.'

2.55pm: Parsons denies several times that he was taking an overly adversarial approach during this period. More than a third of questions about Horizon from forensic accountant Second Sight were deemed by the Post Office as ‘fishing’, out of scope or already answered. Parsons told the Post Office he would try to ‘flesh out’ some of these reasons ‘so it doesn’t look like stonewalling’. He also said there were more questions that could be avoided or where they could ‘fudge’ an answer.

2.45pm: In November 2014, Cartwright King solicitor Martin Smith emailed Parsons and others in Post Office to say that from a criminal perspective, in the mediation scheme, ‘we would advise as a general rule against the disclosure of any documents from a criminal file which have not previously been disclosed to the defendant during the course of the original proceedings’.

Smith added that to do otherwise could encourage criticism of the way prosecutions were conducted or how the prosecution policy was applied, and that ‘clearly such arguments in a public arena would be uncomfortable for POL’.

Parsons replied that questions being raised at this time about Horizon were a ‘massive fishing expedition’.

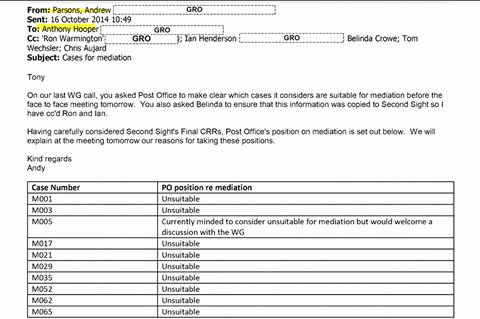

2.35pm: The inquiry sees more evidence that Parsons was not particularly supportive of the mediation scheme. In October 2014 he was asked for an assessment of which cases were suitable for mediation. His assessment is below. Parsons says this was just a 'snapshot' and that hundreds of cases were deemed suitable at other times.

2.30pm: Parsons advised Post Office lawyers in one email from March 2014 to make a ‘targeted attack’ on the Second Sight report on Horizon. He tells the inquiry now that was wrong, adding: ‘I accept that I adopted a reasonably adversarial approach.’

2.20pm: Back from lunch, and moving onto the mediation scheme. Parsons emailed GC Susan Crichton in July 2013 to say mediation was a definite possibility but that the risk was that it would normally be set up with a view to reaching a conclusion.

His email added: ‘I doubt we will ever reach closure on these cases. POL’s comms team would therefore need a robust media strategy to explain why the mediation will, in the majority of cases, fail to reach a consensus between POL and the [sub-postmasters].’

Around the same time, he emailed Crichton (pictured below) again, warning that a suggestion from sub-postmaster leader Alan Bates to set up a mediation scheme may leave Post Office liable and facing making cash settlements. Parsons added: ‘Any hint that POL may be considering cash settlement would encourage the toxic cases, encourage [claimant firm] Shoosmiths and play badly in the media.’

His email, addressed to general counsel Ben Foat, added: ‘If we review them now, PO will be required to disclose any adverse documents uncovered.’

Parsons tells the inquiry the Post Office had already told claimants that these documents existed and it was not incumbent on defence lawyers to review them.

1.05pm: Parsons says in his witness statement that ‘regrettably, this email is worded very poorly’.

He tells the inquiry that he regretted telling Prime to add this, but maintains that the documents in questions did not need to be disclosed at the time.

Blake says he was clearly aware that this was not the case at the time, given that he was trying – in his words - to act ‘in a way that looks legitimate’. Parsons continues to insist he acted properly to resist disclosure of investigation guidelines.

12.55pm: Getting more uncomfortable for Parsons now. The inquiry sees an email drafted by Bond Dickinson trainee Amy Prime which she sent him to be checked over before sending to the Post Office client about prosecution guidelines. The issue came up here. We now find out that rather than Prime writing the finished email, Parsons replied with one addition, and he put forward a paragraph to insert.

That paragraph said: ‘For now, we’ll do what we can to avoid disclosure of these guidelines and try to do so in a way that looks legitimate. However, we are ultimately withholding a key document and this may attract some criticism from Freeths [claimant lawyers]. If you disagree with this approach do let me know. Otherwise, we’ll adopt the approach until such time as we sense the criticism is becoming serious.’

12.45pm: The inquiry returns after another small break and looks at email exchanges between Parsons and Rodric Williams about the Post Office approach to a Panorama programme in 2015.

Parsons wrote: ‘Post Office either does nothing but a bare denial of the allegations and waits for the CCRC, or goes on a full attack – with the former being my strong preference.’

He then goes to ask whether the Post Office could 'start attacking the postmasters credibility by calling out [Noel] Thomas, [Seema] Misra and [Jo] Hamilton as the liars and criminals that they are.' Jo Hamilton, incidentally, was sitting in the front row of the inquiry as this was read out.

He tells the inquiry that 'on reflection that language is too strong', although he had made clear at the time that he would not recommend taking the option of attacking those involved with the programme. He accepts there was a 'grey area' between legal advice and PR advice here.

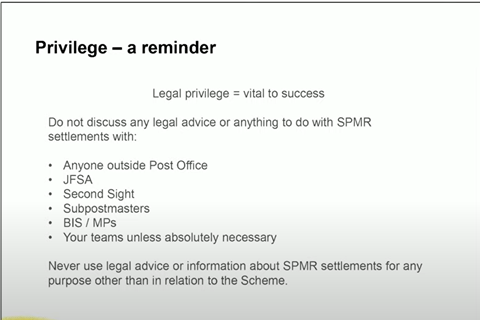

12.10pm: Parsons wrote this internal report in October 2013 updating on the progress of the mediation scheme and setting out a reminder to Post Office staff on privilege. This included an order not to discuss any legal advice or anything to do with settlements and extended to ‘your teams unless absolutely necessary’.

Parsons says this is the kind of position any lawyer would take. Blake asks whether the edict about not sharing information within teams was responsible for a lack of information going through to senior Post Office personnel. Parsons says the intention from his note is clearly that junior staff are not given information rather than senior executives.

The report goes on to say that the Post Office ‘should be slow to concede that Horizon has any technical faults. To do so could open the floodgates to a 'large number of claims'.

Blake points out that at this stage he knew about doubts in at least two historic cases, the Clarke advice on Gareth Jenkins and the three known bugs.

Parsons says this instruction was about only not disclosing any newly-discovered bugs but he concedes: ‘Reflecting on this now I think it sets the bar too high.’

11.50am: The draft note on Horizon risks to insurers went into much greater detail about disclosure failings than the final note. The two are put up side-by-side to show the changes that were made following input from Bond Dickinson.

The draft document had said: ‘The expert evidence of one Post Office witness, Dr Gareth Jenkins of Fujitsu, may have failed to disclose certain problems in the Horizon system.’

The final version stated: ‘It is of concern to Post Office that the expert evidence of one prosecution witness, Dr Gareth Jenkins of Fujitsu, may have failed to disclose certain problems in the Horizon system potentially relevant to a case.’

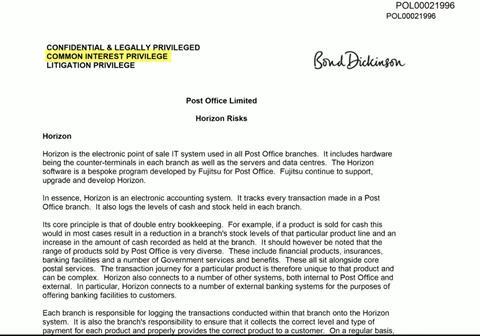

11.40am: Blake takes Parsons to a risk note provided to insurers by Bond Dickinson on behalf of Post Office (see below). It was marked as confidential and legally privileged, despite not appearing to include any legal advice. This is relevant because of earlier questions about Parsons not leaving a paper trail.

Blake says the heading of this document is an attempt to 'cloak it in privilege'. Parsons says lawyers will regularly label documents as privileged but it does not necessarily mean that they are.

Blake: 'It has been disguised here as Bond Dickinson advice covered by legal privilege with the intention that should somebody ask the insurer for a copy they could say it was legally privileged.' He says the likely result is that the contents would not be disclosed.

Parsons accepts this was the intention, but tells Blake: 'Your suggestion was that we were dressing it up as legal advice to try to get it under the badge of privilege. That was not what we were doing.'

11.25am: Blake pushing back hard at this idea that Bond Dickinson (and Parsons) were a mere 'conduit' for setting the terms of reference for the Altman review.

Parsons’ colleague Gavin Matthews wrote to Post Office in-house lawyers warning that Altman should not look at the safety of past prosecutions as this was likely to involve a more significant analysis of lots of cases, and ‘potentially blurs the boundary’ between criminal and civil law.

Another email from August 2013 shows that Parsons was the sole point of contact for the Post Office when discussing Altman’s review.

He tells the inquiry: ‘We were instructing Brian largely because it made it administratively more easy for Post Office. I don’t think Post Office were expecting us to give them any advice in criminal law because they knew we were not criminal lawyers.'

Facing further probing, Parsons continues to insist Bond Dickinson was a conduit and that its lawyers were ‘providing a view’ rather than giving advice. Blake questions whether Post Office would have understood the difference.

11.15am: And, we’re back. By mid-2013 it appears that Parsons was taking a much greater role in Horizon issues. The inquiry sees a draft response from Parsons to the CCRC in July 2013 (he says this was the only such letter he drafted). This letter admitted there had been a couple of problems but that there was no systemic issue with Horizon. Parsons was also acting as a ‘conduit’ for the Post Office and his firm instructed Brian Altman KC to review prosecutions.

Altman said in his report it was for the Post Office and its lawyers (including Bond Dickinson) to consider past prosecutions.

Blake asks whether it appears from Altman’s report that the firm was more than just a conduit.

‘That’s what Brian understood,’ replies Parsons.

10.55am: Parsons continues to insist that incriminating records of meetings misrepresent what he actually said. He adds that he would not usually use the word 'produced' in such a context as the minutes have recorded. Blake takes him to another document where Parsons used exactly that word.

Parsons reiterates bluntly: 'I did not advise Post Office against minuting those meetings.'

We go to a break.

10.50am: A second advice from Simon Clarke addressed whether minutes of Horizon meetings should be shredded. Clarke was clear this was not appropriate whatsoever. But minutes from another meeting record that Parsons’ advice was that ‘if it’s not minuted it’s not in the public domain and therefore not disclosable… if it’s produced it’s available for disclosure… if not minuted then technically it’s not.’

Blake says there is a body of evidence that Parsons advised the Post Office not to keep a paper trail. Parsons disagrees, and states on more than one occasion that he did not advise the Post Office against minuting these meetings. He adds that he did not approve any minutes which suggest he advised against keeping records.

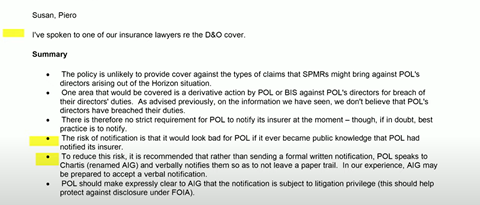

Blake produces another contemporaneous document – this time with Parsons’ advise on what to notify Post Office insurers about Horizon issues.

Parsons stated: ‘The risk of notification is that it would look bad for POL if it ever became public knowledge that POL had notified its insurer… to reduce the risk it is recommended that rather than sending a formal written notification, [Post Office] verbally notifies them so as not to leave a paper trail.'

10.40am: The inquiry looks again at the Simon Clarke advice from 2013 which stated that expert witness Gareth Jenkins was unreliable. Clarke said that the existence of bugs should be disclosed to convicted defendants.

Blake asks if potential miscarriages of justice ever played on his mind. Parsons says he believed that was an issue for the criminal lawyers, not him.

We then see minutes from the first meeting convened after the Clarke Advice, with Parsons one of those present. The minutes state that Parsons commented on the need to ‘limit public debate on the Horizon issue as this may have a detrimental impact on future litigation’.

Another minute records that he advised that ‘if it’s produced, it’s then available for disclosure, if it’s not then technically it isn’t.’

Parsons tells the inquiry he does not believe this minute is an exact record of what he said.

10.30am: From emails at the time, it is clear that Parsons knew in 2013 that the Lee Castleton and Seema Misra cases cast doubt on Horizon. He also knew about three bugs detected by this stage.

He also knew that the Second Sight forensic accountant report might ‘reveal a specific complaint about an error in Horizon’ and that prosecutions were suspended pending this report.

It is clear that Blake is trying to prove there was a bank of information about Horizon that Parsons knew about in 2013.

Bond Dickinson was also asked at this time by general counsel Susan Crichton to advise on an enquiry from the Criminal Cases Review Commission. Parsons’ colleague Gavin Matthews suggested there had to be greater cooperation at this stage between the criminal and civil teams (indicating internal concerns that this may be an issue leading to civil claims).

10.20am: Parsons himself wrote to one sub-postmaster saying there had been ‘two small value unexplained discrepancies’ that impacted their branch. This was common practice, but at no stage in the letter did Parsons mention that the same bug was affecting other branches.

Blake asks: ‘Why not say "you are one of a number of branches affected by this issue"?’

Parsons replies: ‘I don’t believe we gave that any consideration. The instruction was to draft a letter that was focused on each individual branch.’ Despite underplaying the significance of issues to individuals, Parsons emailed Williams saying these were ‘sizeable errors’.

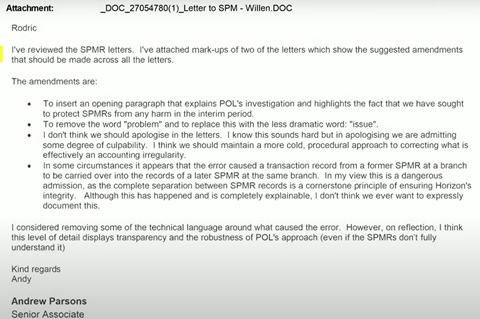

10.10am: Parsons received and amended drafts of letters being sent to sub-postmasters. These letters stated that Post Office had 'thoroughly investigated' branch records even though he did not know if that had happened. Parsons recommended using 'issue' instead of 'problem' and took out apologies being offered to individuals.

He tells the inquiry: 'Sometimes apologies can be interpreted as admission. It is pretty common for lawyers to consider whether the apology is appropriate or not. In my view it leads people to consider that there was an admission of legal fault.'

The inquiry sees an email sent by Parsons to in-house litigation solicitor Rodric Williams. It gives advice about how to write to sub-postmasters and adds that 'I don't think we ever want to expressly document' an error. He denies this was designed to avoid disclosure in future.

10am: Inquiry begins by looking at what Parsons was told in 2013 about creeping doubts about Horizon within Post Office. A report by fraud analyst Helen Rose was sent to him in July 2013 and the presence of a bug found in 14 branches was also flagged up.

Parsons wrote to a colleague saying there was a risk that disclosing any form of an error of Horizon ‘could become problematic if it ends up in the hands’ of the sub-postmaster campaign group.

His email added: ‘My suggest is therefore to make sure that we fully understand the root cause of this error before going public.’

9.50am: Parsons confirms his signature on a lengthy 557-page witness statement. Blake says there are 1,172 exhibits across 18 substantive bundles. It’s going to be a long two days.

Ahead of his appearance, a spokesperson for WBD has said: 'The firm has great sympathy for all those affected by the issues being investigated by the Horizon Public Inquiry and recognises the very real personal impact these have had on sub-postmasters and sub-postmistresses. Under the terms of the inquiry, we are unable to comment further but continue to engage fully in that process.'

9.45am: The lawyers are in, a handful of journalists and members of the public are present, inquiry counsel Julian Blake is on his feet ready to ask questions and Andrew Parsons is seated. Chair Sir Wyn Williams pops up on video screen and we are good to go.