One barrister’s love of cricket and commitment to telling its story shows how the game might face up to and tackle its record on discrimination

Independent Commission for Equity in Cricket did not mince its words this week. Its report, which concluded two years’ detailed work, found there had been a failure to prevent ‘structural and institutional racism, sexism and class-based discrimination’.

The England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB), which established the Commission, apologises ‘unreservedly’ for the game’s record. Some of the worst evidence related to racism.

How does the game come back from such findings? Can horror at what has been estabished, and players’ first hand experience of discrimination, be separated from a love of the game? How can that be achieved?

I think a starting point can be found within the grounds of Lord’s at the Marylebone Cricket Club Museum. This is where Daniel Lightman KC, a highly respected barrister, observant Jew and member of the MCC, has co-curated a one-room exhibition on the contribution of the Jewish community to cricket.

With his co-curator communications professional Zaki Cooper, with whom he wrote the book Cricket Grounds from the Air, Lightman has brought together artifacts and stories to show what actor Stephen Fry, current president of the MCC, describes as some of the Jewish community’s ‘submerged stories’. Those stories are of achievement, everyday involvement – and of course the prejudice that players faced.

Lightman speaks from experience here. He was a keen cricketer at school, but on Saturdays could only walk from home to take part in a match, ruling out most away matches (his faith prevented him from travelling on the Sabbath).

The head teacher sought to make an example of him, Lightman recalls, stating that players should make themselves available, and ‘the head coach told me in front of all the other boys, it was wrong for me to put my “petty superstitions” before the team’.

This gave him an ‘affinity with the difficulty Jewish cricketers faced in their life’.

Lightman personally collected about half the objects displayed, and others loaned by players or their families.

Through photos and mementos their stories are told. There is Norman Gordon (1911-2014), who played for South Africa. Gordon spoke to Lightman when in his 90s, when the latter recalled ‘here comes the Rabbi!’ being shouted as he ran up to bowl in his 1938 test debut against England. Gordon took five wickets that innings.

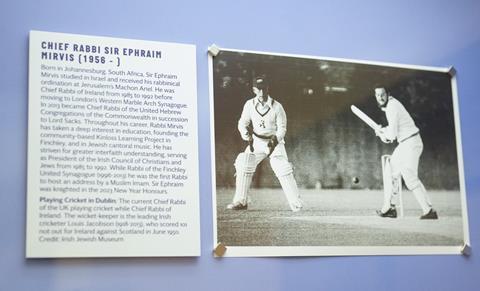

There is striking photo of the current Chief Rabbi Sir Ephraim Mirvis (1956- ) batting in Dublin, while Chief Rabbi of Ireland (the wicket keeper was leading Irish cricketer Louis Jacobson).

Then there’s Sid O’Linn, real name Sidney Olinsky (1927-2016), who changed his name, preferring to face anti-Irish prejudice than anti-semitism. He played for South Africa and Kent.

O’Linn’s judgement may have been spot on. The exhibition also features Percy Fender (1892-1985), the Surrey captain, wrongly thought to be Jewish, on account of his appearance. In the overheard words of an MCC president, considered ‘the smarmy Jewboy’. Contemporaries thought Fender should have captained England in the 1920s. He never did.

Lawyers and lawmakers also feature in this history. Master of the rolls Sir Archibold Levin Smith (1836-1901) played for ‘Gentlemen of Sussex’, and in 1899 became the first Jewish president of the MCC. Lord Dalmeny (1882-1974) captained Surrey, and on being elected an MP in 1907 continued to play for the county. He was president of both Surrey and the MCC.

Lightman has included the Jewish women cricketers he could identify. There is Netta Rheinberg (1911-2006), the Home Counties, Middlesex, who managed the 1948-9 England Women’s team tour to Australia and New Zealand. Ruth Buckstein (1955- ) played for Victoria and Australia, scoring two centuries in the 1988 Women’s World Cup.

Lightman is quite clear in his belief that cricket, and cricketing sides, benefit from diversity – the benefit of an outsider view on established norms. He points to the Lyon brothers, Dar and Bev, who played for Somerset and Gloucestershire. Strategically innovative, they were advocates of ‘brighter cricket’. Dar, a lawyer, became Chief Justice of the Seychelles.

It is striking that the material Lightman and Cooper had to draw on for the international game would have been greater, had South African Jewish cricketers not found themselves caught up in the Apartheid era boycotts. Several careers were cut short. Still, some became active campaigners against Apartheid; others, from the 1990s, helped build a multiracial game in the country.

It is worth returning to the questions of what the ECB might learn from Lightman and Cooper’s exhibition, as it confronts its record on ‘equity’ and tries to plan a better future.

‘It is important these stories which have often been supressed are made known,’ he tells me. ‘If they are not known, people won’t know that others faced it.’ Society’s anti-Jewish prejudice is, he points out, still ‘alive and kicking’.

This KC has also noticed a prominent example of what ‘good’ looks like here. Lightman has noticed the promising young South African cricket player, school boy David Teeger. As an observant Jew, Teeger has the same long walk to home matches played on a Saturday.

But unlike the young Lightman, Teeger is not singled out for censure. Instead, on the Saturday morning of the team’s last home fixture of the season, his team mates and coaches arrived at his home and walked to the school pitch with him.

After all, the primary aim of antidiscrimination law and practice is not punishment of offenders. It is to make things better. In that process, shared passions like cricket and accurate story-telling help.

The MCC Museum is open to members and anyone who has entry to Lord’s for a game or event. This exhibition, in the museum’s community room, does not currently have an end date