What a shame Theresa May did not see a new play highlighting the thesis that ‘parliamentary democracy trumps all’.

Cookham is a gorgeous place on the river Thames: all mellow brick and immaculate lawns. Politically, it looks like what it is: Conservative heartland. This is, after all, Theresa May’s constituency.

But Cookham harbours an artistic streak, reflected in the work of artist Sir Stanley Spencer, who painted in what he once called ‘a village in heaven’. Cookham still holds a regular arts festival. And – at the behest of local resident and former Law Society president Charles Elly – that is why I was on a panel to discuss the opening performance of a remarkable play, Regulation 18B: No Free Man, the setting of which is historical but the theme contemporary.

The play dramatises the issues in a judgment of Lord Atkin. Those with as skimpy a legal education as my own may need a reminder. Lord Atkin was a leading member of the House of Lords in the 1930s and early 1940s. Even if his name has faded, his judgment in Donoghue v Stevenson has not. That slug in the bottle still crawls deep in the memory of almost every former law student.

Lord Atkin has another claim to immortal memory. Shortly before his death, he delivered a devastating, but dissenting, judgment in Liversidge v Anderson. His speech was a coruscating attack on the home secretary of the time, who asserted power to intern aliens without indicating cause, and his acquiescing fellow judges.

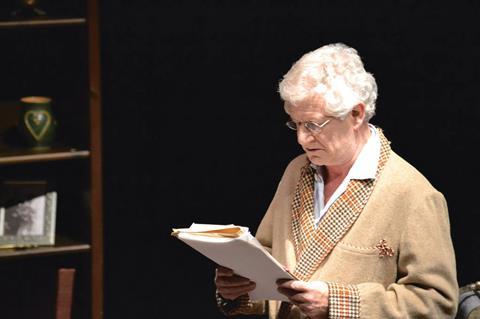

The author is a practising lawyer, Scott Wright, head of labour and employment at US firm Faegre Baker Daniels. The play’s success suggests an alternative vocation should he tire of the law. The drama comes from the invention of a fictional meeting the night before the judgment is to be delivered. Lord Atkin’s one-time protege, Lord Wright, comes to see his now ailing mentor. He wants him to retract, or at least tone down, his critique. In particular he does not like comparisons of the home secretary to Humpty Dumpty (‘When I use a word… it means just what I choose it to mean, neither more nor less’), nor the allegation that he and his colleagues are ‘more executive-minded than the executive’.

The script leaves you guessing about motive. Does Lord Wright really fear that his old master will be publicly humiliated by the press? Does he worry more about how posterity will see his own connivance? Does he believe that, at a time of war, the judiciary should defer to the elected executive? Does Lord Atkin’s love of rhetoric get the better of him?

The play has now completed an opening round of performances that included one at Gray’s Inn. If you get a chance, go and see any new one. The writing is good enough to keep you entertained and you could safely take a non-lawyer.

It was a pity that Theresa May was unable to come. Her presence had been rumoured. You may remember that she argued that ‘literally’ (‘I kid you not’) an asylum-seeker’s relationship with his cat had prevented his deportation under, presumably, the cat’s article 8 rights. Literally, this was, of course, both unlikely and untrue.

She remains, however, an opponent of the Human Rights Act. As home secretary, she wants untrammelled powers of deportation. Her argument, like home secretary Anderson in 1940, is that she is democratically accountable to parliament and that is enough.

And May is not alone. Most of Tony Blair’s home secretaries agreed with her. Charles Clarke, David Blunkett and John Reid, a somewhat bombastic trio, all whinged about the act.

‘We cannot,’ these once powerful ministers intoned with one voice, ‘have judges looking over our shoulder when we have to protect the state at a time of what amounts to war.’

That was precisely the issue addressed by Lord Atkin. And his famous conclusion? ‘In England, amidst the clash of arms, the laws are not silent.’ The effect of his Donoghue judgment on negligence was immediate. Liversidge had more of a delayed action as judicial review took 30 years to catch up.

The act is a further development of that movement for the constitutional accountability of political power. And behind the forthcoming debate on the act to be led by the government we are likely to find the assertion of the Anderson-May thesis that parliamentary democracy trumps all. This is the real issue behind the touted new Bill of Rights. It has little to do with rights – it is all about which institution will construe them.

Back in 1942, there was no evidence that Liversidge was a fascist. Quite the reverse. But, he was caught in a web of political expediency. Democratic accountability is, of course, important. But Lord Atkin, ably brought to life by a practising lawyer in a lovely Thames village not that far from Runnymede, invites us to consider when it is just not enough.

Roger Smith is visiting professor at London South Bank University and former director of human rights group Justice

2 Readers' comments