Law firms should involve all staff in preparing for disaster recovery, hears Jonathan Rayner.

Crises are impartial predators: they prey on sole practitioners and magic circle firms alike.

With proper planning they can be survived, but sooner or later every firm can expect to face a crisis that threatens its reputation or even its very existence. The crisis could come from outside the firm, with a cyber-attack, for example, or criminal fraud. Or it could have its roots within the firm, when a colleague steals from the client account, for instance. The trick, management gurus say, is to plan for every such eventuality and to have the team in place to act quickly to neutralise – or, at least, minimise – the fallout.

Let’s examine that last proposition. You could spend weeks imagining every conceivable disaster that could hit your firm. These disasters would range from force majeure, to the more prosaic likelihood of a member of staff unwittingly importing a virus on to your computer network that allows criminals to read confidential data.

These two scenarios have much in common. They could both mean that service to your clients has been abruptly stopped and that their data and funds are endangered. Both firms share the need to protect their clients, resume normal service as soon as possible and repair their reputations in the eyes of the world.

They also both need to convince the regulators, who will come asking questions, that they have fulfilled their obligations. The Information Commissioner, whose role is to enforce the Data Protection Act, is uncompromising: firms must take adequate measures to protect data from loss, including theft and accidental loss. Ditto the Solicitors Regulation Authority, whose principles four and eight oblige solicitors to act in the best interests of clients and adhere to sound risk management practices.

Firms are required to demonstrate that they have trained staff in how best to protect against data loss. Failure to comply with these edicts can excite the regulators’ wrath, with possible financial penalties, interventions and criminal proceedings to follow.

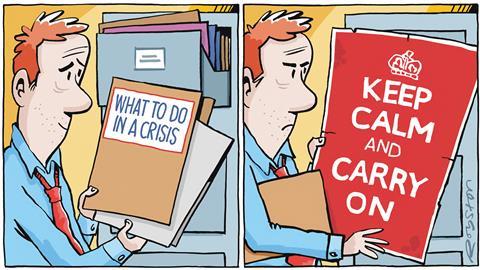

‘It’s a minefield out there,’ says Paul Bennett, a partner at Shrewsbury firm Aaron & Partners and chair of the Law Society’s Small Firms Division. ‘All firms should have a comprehensive crisis plan prepared long before any actual crisis occurs. It should be regularly updated and tested, too. You can’t wait until you’re in trouble. It’s all too easy to make bad decisions in the heat of the moment.’

Bennett advises firms on business continuity planning and other management issues. His core market is small to medium-sized law practices, although he also works with international and City firms as well as doctors’ surgeries and accountancy firms. ‘My experience,’ he says, ‘is that when something goes wrong, law firms tend to have an IT business continuity plan – because the SRA has told them to – but it is often basic and out of date.’

What else can go wrong? Bennett replies: ‘You have to consider an illness, road accident or injury happening to a senior management figure. Even volcanoes can play a part. When an erupting volcano in Iceland grounded lots of flights in 2010, one firm I worked with had a senior partner stranded overseas. Was he equipped to work from a hotel room or airport lounge? Have you planned for when a key team member simply cannot get to their desk?’

He gives a second example: ‘There was a banking error, but a sole practitioner still had to repay almost £300,000 that same day. The sole practitioner had a plan, which was implemented. And because he had prepared for such a contingency and because he had cooperated, the SRA ruled that there had been no breach of its accountancy rules. That’s exactly how a plan should work.’

What about a threat coming from within the firm? Bennett responds: ‘It was a Friday afternoon and one of my clients discovered that an employee had secretly set up a separate claims management business within the firm as a supplier to the firm. The implications were horrendous. There was an obvious conflict of interest, with the employee marketing his business to clients and consumers without declaring the connection to the law firm. The SRA had to be informed and disciplinary proceedings started. And what do you tell the other staff?

‘We worked with the firm to control the reputational and other damage that it was exposed to. There are always some eventualities – such as the illegal or just plain silly actions of an individual – that are difficult to plan for.’

Kysen public relations managing director Clare Rodway says ‘scenario planning’ is central to managing a crisis. ‘If you are going to be jumped by a press enquiry on a Friday afternoon, then you need to pre-agree the message you are going to put out at the very first hint of a disaster looming. All staff, senior and junior, should be in the loop because journalists have a way of avoiding the spokesperson and getting confirmation from, say, a receptionist.’

Surely journalists never act in a devious manner? Rodway says that a common journalistic ruse is to sound sympathetic. It must have come as a real shock to you all when Mr Bloggs cleared out the client account, a journalist might say. And when the hapless employee replies that Mr Bloggs was the last person you would expect to be dishonest, the journalist has confirmation.

Be prepared – top tips

- Identify five to 10 events that would create the most damaging internal or external crisis for your firm.

- Prepare a strategy for dealing with each of these disasters – including deciding how the firm will respond; who will be the key decision-makers and spokespeople; how and what to tell staff and clients; and whether to contact the SRA and police.

- Insist that lawyers and spokespeople practise the above crisis management techniques through role-playing and, where appropriate, with the help of PR, human resources and IT professionals.

- Take advantage of the free Law Society website course Cyber security: Essential training. The SRA has published Spiders in the web, also online.

- Consider the Cyber Essentials scheme, a UK government-backed and industry-supported scheme to guide businesses in protecting themselves against cyber threats.

‘You need a communication plan,’ continues Rodway. ‘Everyone should have a copy or it should be stored in the Cloud [a network of remote servers, rather than a local server or personal computer, that stores data securely]. It should include a telephone tree, so that everyone is quickly informed, as well as out-of-office contact details for key decision-makers. Whatever the disaster, you’ll need to get hold of the decision-makers immediately.’

Richard Elsen, one of the founders of legal PR consultancy Byfield, says: ‘You don’t want to waste valuable time agreeing a way forward when a crisis hits. Your risk and compliance people should have identified the areas of most risk and you should then have put in place the protocols and processes to manage the situation. You should have a clear chain of command. Messages to the press, clients and staff should all have been approved. This pre-planning means you are better able to deal with a crisis that has come at you out of left field.’

What are the areas of most risk? Elsen replies: ‘A cyber-attack is almost inevitable for most businesses. There are criminal gangs constantly attacking targets. These gangs are highly skilled and often a step ahead of the game, with new techniques that are increasingly difficult to defend against.’

What about non-cyber threats? ‘Cases of financial fraud or a member of staff stealing client money are not uncommon. There is alleged inappropriate behaviour, often of a sexual nature, which always attracts the public’s interest. The loss of the firm’s biggest client can lead to fears of economic instability. The word quickly gets around, too, when unhappy clients complain about a firm’s or individual’s supposed misconduct. And so forth.’

Solicitor Peter Wright is managing director of Yorkshire firm DigitalLawUK, which describes itself as ‘the UK’s only law firm specialising solely in data protection, privacy, cybersecurity and social media law’. He lists a catalogue of threats. ‘Half of all large businesses and one-third of all small and medium-sized enterprises were hacked in 2013,’ he says, ‘at a cost to companies ranging from thousands of pounds to £1m.’ He adds: ‘Reputational damage suffered by your firm will for time immemorial come up whenever its name is Googled, despite your best efforts to manage the crisis and repair your image.’

Someone hacking into your Twitter account can result in ‘prejudicial information’ being disseminated in your name, affecting not only your reputation, but also the value of the business. Business online networking group LinkedIn can also backfire if you recklessly ‘link’ with a stranger, who proceeds to know your profile well and make informed guesses about the passwords you use to protect your bank and other accounts.

Wright is not being alarmist: ‘We invited some “ethical hackers” to a recent event. It took them seconds to get into laptops, desktops and saved passwords. They could even see the computer users through the webcam eye.’

Any more bad news? ‘There’s malware,’ he replies, ‘which hackers use to clog up your machine and then try to sell you a product to speed it up again. There’s ransomeware, which freezes your machine and you have to pay to unfreeze it. And there’s denial of service, which overloads your system with maybe 500,000 hits in a few seconds so that it collapses and hackers find it easier to get into.’

So we are all helpless potential victims? ‘Not if all staff are constantly vigilant and constantly updated on the latest scams,’ replies Wright. ‘Governance cannot be outsourced. Mistakes are always your fault, not somebody else’s.’ He continues: ‘Staff should not open emails unless they are confident that they come from someone they trust.

‘Passwords should not be obvious. Don’t use 123456 or Password. Think of something more complex that you can remember, but others cannot.

‘Read the cybersecurity guides published by the Law Society, SRA and government (see box above). Don’t let staff use their own devices, such as laptops and tablets, without first getting IT to check them out. And shred all confidential papers.’

The internet is fraught with peril, then? ‘Yes, but then so is talking business on your mobile phone while on the train or letting strangers look over your shoulder at your laptop. You need to be very careful – always.’

Jonathan Rayner is Gazette staff writer

No comments yet