After Magna Carta, Waterloo and Gallipoli you may think another extravagantly celebrated anniversary is the last thing we need. Hard luck, because next year we are in for a centenary commemoration which, among other things, will put British justice - historical and not so historical - in the international dock.

The good news is that the commemoration is being approached in an open-minded spirit that could put the official celebrations of 1215 to shame.

The centenary is of course that of the 1916 Easter Rising, an iconic moment in the foundation of the Republic of Ireland. The standard version of the story - at least, the one you'll find in Hollywood - was that on Easter Monday 1916, the Irish people rose up against 700 years of oppression by the English/British crown. They were crushed brutally by British artillery and their leaders summarily executed after kangaroo court-martials. Nonetheless the blood sacrifice opened the way to freedom in 1922.

This was very much the version celebrated by the rising's 50th anniversary. But Ireland has changed a great deal since 1966. Last weekend, I heard the country's president explain why the standard narrative is not sufficient for 2016. The poet, academic and politician Michael D Higgins was speaking at the Glencree Centre for Peace and Reconciliation, just south of Dublin, established to bring together what are euphemistically called the 'different traditions' in Irish history.

In a 6,000-word address, packed with academic and literary references that would be strangled at birth in Whitehall, Higgins said: 'For too long our understanding of 1916 and the surrounding period was hindered by an assumption that we can more easily make sense of events, and indeed our own sense of individual and national identity, if we keep historical narratives simple and homogenous. We must in commemorating challenge this urge to over-simplify. Complex events demand a consideration that respects complexity, seeks to unravel it rather than invest a simplicity that leads away from knowledge, even to ideological manipulation.'

Of course Higgins was talking particularly of the need for the commemoration to embrace different shades of loyalism. This includes not just the Ulster protestants, for whom 'commemorating 1916' means remembering the slaughter of the 36th Ulster Division on the Somme, but the majority of the Irish people who did not side with the rebels.

Other narratives that need to be unravelled include the role of women - who played an extraordinarily active role in the rising, but were largely airbrushed out by the free state - and that of the church. To judge by conversations at Glencree, a particularly emotive re-examination will be that of defining 'martyrdom' when it involves elements of intent, whether in the actions of the uprising's leader Patrick Pearse, subsequent hunger strikers or today's suicide bombers.

More generally, commemorations will also have to deal with the question - highly charged in Irish politics - of whether the uprising's bloodshed hindered rather than helped the creation of an independent Irish state.

Fascinating though that debate will be, it is off-topic here. Not so the British government's quasi judicial response to the uprising, which raises questions today about the appropriate response of a liberal democracy (in 1916 only a relatively liberal, partial democracy) to armed insurrection.

Here, even after a century, there seems little scope for revising the standard interepretation that the government's reaction was brutal and catastrophically counter-productive.

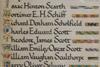

One of the first mentions of the uprising in the contemporary legal press appeared on 26 April 1916: an ominous notice suspending section 1 of the Defence of the Realm amendment Act 1915, which had granted British subjects accused of offences under the act the right to be tried by a civil court rather than court martial. Thus empowered, hastily assembled field general courts martial held in camera briskly tried the obvious leaders (and at least one who was not) for 'waging of war against His Majesty the King, such act being of such a nature as to be calculated to be prejudicial to the defence of the realm...'.

Infamously, 15 men thus convicted were shot a day or two after their trials, with no right of appeal. The last of W.B. Yeats' 'sixteen men' was Roger Casement, hanged in Pentonville Prison in August after a trial that will no doubt attract its own exhaustive re-examination next year.

Even at the time, the swiftness of the executions caused unease at the heart of the British establishment. Asquith, the liberal and legally quaified prime minister, seems to have reacted with consternation. He had the political sense to order that no woman be shot without his say-so, sparing the extraordinary Constance Markievicz the firing squad. (Though he could have intervened sooner in the cases of the men.) On 13 May, a weekly paper, the Solicitors' Journal, commented that: ‘Thirteen executions for civil rebellion under sentences of martial law are a phenomenon long unknown in British history.’ Likening the response to the Bloody Assize of 1685, it called for the authorities to bring the prisoners before civil courts.

These concerns had some effect. The executions stopped, and one third of the suspected rebels hastily rounded up were released reasonably promptly, albeit after some brutal treatment. The rest were amnestied the following year - after the radicalising experience of internment, from which future governments might have taken lessons.

There may not be many strands of 1916 history that the British authorities can unpick with pride, but a century on we are entitled to ask whether any other imperial power at the crisis of the war would have preserved at least some concern for the rule of law. Or at least for the consequences of ignoring it.

No comments yet