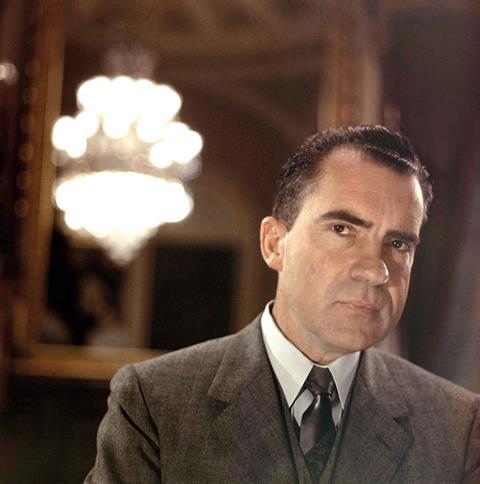

It is difficult to bring home the enormity of the Post Office Horizon IT scandal for the legal profession in England and Wales. One way would be to compare the impact with the famous break-in into the Democrats’ campaign office in the Watergate building and ensuing cover-up. That brought down President Nixon (pictured below) and led to disciplinary proceedings being brought against 29 lawyers.

How can the two be compared? As the Gazette reported, the Post Office scandal is arguably the most widespread miscarriage of justice in British history, and the inquiry into it is about to turn its spotlight on the role of lawyers. The focus is likely to be whether the lawyers put a thirst for victory above their wider duties. No one would suggest that they were involved in anything like the burglaries, perjury and bribery that ensnared the Watergate lawyers. But as the author of Watergate and the Law Schools put it in 1975: ‘There is a difference in application, but not in underlying principle, between those who would state that it is the lawyer’s duty to use any means… to achieve a victory and those who would break into [an] office or engage in illegal wiretapping.’

It has come to light that after one sub-postmaster was sent to prison in November 2010 (unjustly, it transpired), a senior Post Office lawyer celebrated the victory in an email, observing that: ‘… [the sub-postmaster had made] an unprecedented attack [on the Horizon computer]… It is to be hoped the case will set a marker to dissuade other defendants from jumping on the Horizon bashing bandwagon.’

In fact, the one thing Horizon needed was to be bashed a lot harder, a lot sooner, by the Post Office’s own solicitors. Another lawyer is alleged to have warned a sub-postmaster: ‘We will ruin you.’ (This accusation has been strongly rejected). Those may prove to be the tip of the iceberg. Solicitors were involved at every stage of the saga; the number may match the 29 involved in Watergate.

Watergate led to much soul-searching within the profession in the US. It resulted in a requirement that law schools provide legal ethics education. The view was that ‘although we cannot ensure that any attorney will in fact behave ethically, we can at least be certain that he is fully aware of what his ethical duties are’.

Ever since, law schools have employed lecturers in legal ethics who run the mandatory courses; some of them also have practices advising law firms. It is a recognised discipline. Despite the lawyer jokes in the US, all lawyers have received training on legal ethics, there is an extensive library of textbooks and commentaries, there are thoughtful debates on wide-ranging issues, and there is an Association of Professional Responsibility Lawyers, dedicated to bringing about positive change in legal ethics and the law of lawyering.

In England and Wales, when it comes to studying legal ethics, prospective solicitors generally study the SRA Standards and Regulations, whether for the Legal Practice Course or the Solicitors Qualifying Examination. There is a widespread view that ‘legal ethics = the SRA Principles + the SRA Codes of Conduct’. Wrong: legal ethics do not begin or end there.

Take for example the solicitor’s obligation towards third parties – sub-postmasters if you will. There are rules and SRA Principles that help. But the deeper question concerns the societal role. Does the solicitor have a role as a moral agent of justice? What does it mean to be an ‘officer of the court’? Should solicitors serve the public interest, and if so, how? If the solicitors acting for the Post Office, in-house and external, had been used to engaging with legal ethics, perhaps the wrongful convictions, the ruin of lives, would have been avoided. We would at least be certain that they were fully aware of what their ethical duties were.

In England and Wales, there is only a handful of academics who specialise in legal ethics, and a handful of solicitors like the writer who provide training in legal ethics to law firms. Likewise there is only a handful of student textbooks on the subject. It is not the same in the medical profession: medical students spend much of their time on the subject. Ironically, you can do an LLM in medical law and ethics, even a PhD, but not in lawyers’ law and ethics.

And it is not only lawyer involvement in the Post Office scandal that lends urgency to the issue. A headline in the FT (10 May) tells its own story: ‘Big law firms fall out of fashion with idealistic Generation Z’. It may become increasingly difficult to persuade bright young lawyers to represent corporate clients which have a bad environmental, social and governance profile.

That may result from a lack of understanding of the ethics of the lawyer’s role. If budding idealistic lawyers were taught about the so-called ‘standard conception’, they would learn that a solicitor should adopt a neutral stance concerning the morality of their client. The importance of this is self-evident when it comes to criminal law, because it is plainly a good thing to see that a suspicious suspect receives legal representation of the right sort. So too with Big Oil, perhaps? Discuss, as the examiners would say.

Francis Dingwall is a partner in Legal Risk LLP, specialising in professional regulation and professional indemnity insurance

9 Readers' comments