Duty solicitors are a staple of every modern detective drama. But with numbers plummeting, their attendance is becoming less dependable in real‑life police stations. Catherine Baksi reports

The low down

Since 1986 the criminal duty solicitor scheme has provided a guarantee of free legal advice for suspects attending police stations in England and Wales. Practitioners can be called out at any time of the day or night, often to distant locations. Duty solicitors are a critical cog of our criminal justice system, but they are poorly paid, fed up and getting older. The average age is 51 and numbers are in steep decline. At one time, the work was viewed as a gateway to new and potentially lifelong clients, and lucrative Crown court work. But unsocial hours and low legal aid rates mean the role is no longer financially viable for many. Recent increases in pay are viewed as a sticking plaster. So where is the next generation coming from?

Before 1986, ‘it was hit and miss whether you got a solicitor at the police station or not’, the Law Society once told the Gazette. What changed that year was the creation of the duty solicitor scheme. Co-developed by the Society and Home Office, after tougher safeguards for suspects were introduced by the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE), the scheme ensured the practical availability of free legal representation at police stations.

The scheme’s introduction complemented other reforms such as the tape-recording of interviews and control over the length of pre-charge detention. Taken together, the measures were intended to avert unreliable confessions, fabricated evidence and misconduct by police officers.

It is hard to overstate the significance of PACE and the duty solicitor scheme to the credibility and fairness of criminal justice in England and Wales. ‘In all the big, classic miscarriage of justice cases, the faults happened in the police station,’ says Chloe Jay, senior partner at Shentons Solicitors in Winchester. The Birmingham Six and Guildford Four miscarriages, for example, both had their roots in what went on at police stations pre-PACE.

Lowest and most vulnerable

A qualified duty solicitor who represents clients at all stages of the criminal justice process, Jay notes that it is at the police station where clients are at their lowest ebb and most vulnerable. ‘They are often in shock after having been arrested and solicitors need to be quite robust on their behalf,’ she stresses.

It is perhaps a bitter irony, then, that duty solicitors – lawyers who are on call and travel miles to police stations, day and night, 365 days a year – are among the profession’s lowest-paid. No wonder numbers are falling fast.

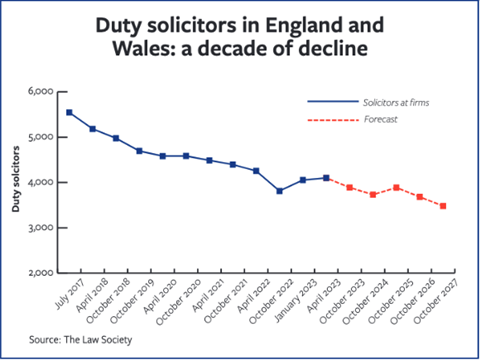

Analysis of Legal Aid Agency data by the Law Society shows that the number of duty solicitors has fallen from 5,546 in 2017 to around 4,000 today. The Society has been informed of cases where firms are struggling to cover duty schemes, and the police are forced to release suspects because interviews cannot go ahead without legal representation.

Demographic time bomb

Chancery Lane’s analysis reveals that duty solicitors are getting older, too. Last year, less than 4% of duty solicitors were under 35. The average age as of April 2024 was 51. By comparison, 24% of all practising certificate holders were under 35 in 2024, while the average age was 44.

The Society predicts that the number of duty solicitors will continue to fall, to fewer than 3,500 by 2027.

With regard to delivering the comprehensive geographical coverage upon which the success of the scheme depends, these trends amount to a demographic time bomb. There are no criminal law solicitors under 35 in Cornwall, Lincolnshire, Wiltshire or Worcestershire – and only one in Norfolk, Shropshire and Warwickshire. In Bristol, Cornwall, Devon, East Sussex, Lincolnshire, Wiltshire and Worcestershire, more than 60% are over 50.

Andrew Bishop, a consultant at Bishop & Light Solicitors in Brighton, has been a duty solicitor for 33 years. He tells the Gazette: ‘At one time, there were 65 solicitors on the local rota. Today there are only 31.’ More practitioners leave each year, he adds.

The current ‘crisis’, he argues, does not merely affect solicitors, but ‘places the entire criminal justice system at risk’.

Bishop recalls: ‘In the first two decades of my career, solicitors often sought out work, striving to win clients and build a reputation.’ Even ‘challenging clients’ were wanted, because they might become repeat customers. Moreover, hourly rates, which could be enhanced for difficult cases, reflected the time and complexity involved.

The fall in duty solicitor numbers and increase in arrests mean that work remains plentiful, but Bishop is clear: ‘Solicitors are overwhelmed.’

The practical issues are plain. Duty solicitors are obliged to act for anyone requiring representation at the police station. However, as Bishop explains, fixed fees, which often pay solicitors the same regardless of the complexity of the case, mean that practitioners are declining to apply for legal aid or to take on complex or problematic cases beyond their duty obligations.

Firms struggle to find people available to go to the police station at weekends and out of hours, says Jay. More work is therefore being done by police station representatives who are not qualified solicitors. (Police station representatives are staff from law firms, not necessarily lawyers, who are trained to attend interviews with suspects who are being questioned by police officers. Representatives have to be qualified under the Police Station Representative Accreditation Scheme. Non-lawyer representatives must have the Law Society’s Police Station Qualification.)

‘While [these reps] are experienced in dealing with police station cases,’ Jay adds, ‘they will never have conducted a criminal trial and will not have the breadth of experience which that brings to advising at the police station.’

Charge sheet: fees inflated away

The fixed fee for duty solicitor work is paid for whole cases, and can include initial advice and attendances at the police station, and attendances for returns on bail.

Since 2008, rates have differed around the country, based on historical averages dating from 2006/07.

In December 2024, rates for some schemes rose by 11%, taking fees in 173 out of 213 non-London schemes to £223.52 (ex VAT), and to £264.45 in 26 out of London’s 32 schemes.

The most recent consultation, which closed earlier this month, proposed harmonising all police station fixed fees at £320.

The proposed rise, says Law Society president Richard Atkinson, is a welcome step in the right direction, but does not address the need for enhanced payment for unsocial hours, working on the most complex cases, and for attendances by highly experienced solicitors.

Andrew Bishop, a consultant at Bishop & Light, stresses that the fee rises must be viewed in the context of historical stasis and cuts: ‘Before 2023, legal aid fee rates had not seen any increase since 2001.’ In 2014, they were subject to an arbitrary 8.75% cut.

Inflation, of course, has continued to erode the real value of the salaries paid on the back of these fees. Goods and services that cost £100 in 2001 now cost £190, according to the Bank of England’s inflation calculator.

The system has gradually shifted from hourly rates to fixed fees, which makes precise comparisons problematic. However, Bishop insists the ‘overall trend has been a significant reduction in real-terms remuneration for legal aid work’.

Although he welcomes the suggested rise, Bishop argues: ‘The proposed fee increases… are not enough when seen in the context of over 20 years of real-terms cuts.’

Without a mechanism for annual index-linked rises, he notes, recent increases will also soon be eroded by inflation. And where is the incentive for firms to invest in training and recruitment?

‘When I began practising in the 1990s,’ Bishop says, ‘legal aid fees were routinely adjusted each April in line with inflation. Only a return to this approach will provide the certainty needed to safeguard the future of the profession.’

Flat rate

Since 2008, duty solicitors have worked for a fixed fee, which is currently an average of around £240 (ex VAT) – regardless of the day, charge or length of time taken. (See box, above.)

‘There are not many professions where you are paid the same rate whether it is 2pm on a Tuesday afternoon or Christmas Day,’ says Katy Hanson, managing partner at Welch & Co in Wales and a Criminal Law Solicitors’ Association committee member.

Another headache for duty solicitors, points out Richard Atkinson, president of the Law Society and a specialist criminal defence solicitor, is that the work has become more complex because of the increase in electronic evidence. As a result, the time solicitors have to spend in the police station has increased.

Because there is also no enhanced fee for attendance during unsocial hours, Atkinson adds, firms pay fee-earners more for night or weekend work but get nothing extra from the Legal Aid Agency. This also serves as a disincentive to send out the most experienced fee-earners.

Atkinson adds: ‘Unsocial hours also make police station work highly unattractive for those with caring responsibilities, and many female solicitors, as attending police stations at night can have security concerns.’

Given the average age, jokes Stuart Nolan, managing director at DBT & Partners in Liverpool and chair of the Law Society’s Criminal Law Committee, ‘the one thing you can say about duty solicitors is that they are generally old and experienced’.

Looking to the future, he stresses: ‘If you want to attract good people, you have to pay proper fees.’ That is even more the case for the next generation of lawyers, who are qualifying with large debts and are even less inclined to enter the criminal law because of the low rewards on offer.

Who pays

So is there any cause at all for optimism?

In his 2021 Criminal Legal Aid Review, Conservative peer Lord Bellamy recommended an immediate across-the-board rise of 15% in legal aid rates for criminal defence solicitors and barristers. This month, the Ministry of Justice consulted on a 12% pay rise for solicitors working in police stations, as well as at courts and prisons.

Responding, the Law Society welcomed the government’s proposals as a ‘first step after so many years of neglect and underfunding’. But Chancery Lane warned ministers the rise is not enough to keep firms’ heads above water and called for enhanced payments for solicitors working ‘unsocial hours’.

Atkinson calls on ministers to provide ‘sustained investment’ in criminal legal aid ‘to show current duty solicitors that there is a future in their profession and encourage others to join the profession’.

Courts crisis

The duty solicitor problem is, of course, just one element of the broader criminal justice crisis addressed by Sir Brian Leveson in his report on the courts that was published earlier this month.

In addition to well-publicised reforms such as limiting jury trials, Leveson recommended an increase in out-of-court resolutions (OOCRs).

'If there are insufficient duty solicitors, attempts to reduce the Crown court backlogs will be fatally undermined'

Richard Atkinson, Law Society president

The retired Court of Appeal judge stressed that a ‘key challenge’ here is the ‘dwindling availability of criminal law solicitors’ – specifically duty solicitors. The latter, Leveson said, play a vital role in providing unbiased advice to defendants on whether to accept an out-of-court disposal.

‘The implication is clear,’ Atkinson warns. ‘If there are insufficient duty solicitors, attempts to reduce the Crown court backlogs will be fatally undermined.’

In addition to that shortage, what Atkinson calls the ‘disconnect’ between duty solicitors and the police could reduce the take-up of OOCRs. Such disposals are dependent on suspects making admissions in interview.

Solicitors can play a role in encouraging clients to follow this path, says Jay, but the police ‘need to engage with us more’. Even now, she says, the police often don’t bother to ask the solicitor’s opinion on whether someone should be eligible for such a disposal.

Other frustrations reported by duty solicitors include: inadequate pre-interview information about allegations; not being allowed to take phones or laptops into custody suites; and, in some places, working conditions, which can be cramped, unclean and unsafe.

Jay also observes that the design of new police stations, where solicitors are locked in consultation corridors to see clients in spaces dubbed ‘tiger traps’, can feel unsafe despite the presence of alarms. In these stations, she adds, solicitors are no longer able routinely to go into the custody area, which removes the opportunity for informal discussions with custody officers that often assist the solicitor and the police.

Hanson and others also report a lack of cooperation and respect at some stations, with police keeping solicitors waiting for hours without explanation or apology.

Additionally, communicating with officers after the police station attendance to find out the outcome of an arrest is often difficult. The length of time between attendance and decision is stretching ever longer, says Hanson.

One London-based police station representative, who asked to remain anonymous, claims that the police at some stations routinely listen in to confidential discussions with clients. The Metropolitan Police denies this.

While he has never suspected that the police listened in to solicitors talking with clients, Nolan says there were concerns during the pandemic when consultations were held remotely via the telephone.

A rare positive noted by Nolan is that increased efforts to divert children and young people away from the criminal justice system have resulted in fewer attendances for them.

Burnt out

In order to be on a duty solicitor rota to attend police stations, which can lead to new clients and potentially lucrative Crown court cases, solicitors must obtain the required accreditation. The slot on the rota belongs to the individual solicitor and not the firm.

Historically, firms would retain retired solicitors on their rotas, enabling them to bag more slots. To stop this, the Legal Aid Agency introduced a minimum number of attendances, which are checked by the contract manager.

While she accepts that tighter controls were necessary, Jay suggests that the pendulum has swung too far. She works predominantly as a Crown court advocate, but also manages the firm. When she has long trials, she can struggle to cover police station work. ‘It is irritating, quite frankly, to have to keep going to the police station to prove my credentials as a duty solicitor when I’ve been qualified 15 years,’ she says.

A duty shift lasts around 24 hours and typically includes five or six cases. But, Jay explains, solicitors often have to work beyond that time to retain the client. And the work can be gruelling: ‘One Easter weekend, a kidnapping came in on Good Friday and I ended up working the whole bank holiday weekend.’

Bishop concludes: ‘At our core, we are committed to representing individuals at some of the most difficult moments in their lives. But the reality is that many of us are burnt out, overstretched, and financially constrained.’

Catherine Baksi is a freelance journalist

No comments yet