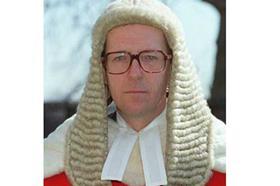

A dilemma over what to do with privileged information that a 'whistleblowing' paralegal disclosed directly to the court has prompted a High Court judge to refer the case to the president of the family division. Mr Justice Holman said the 'novel, if not unique, set of circumstances' required consideration at the highest level.

The case involves a couple who divorced in 2013. At the time the husband was represented by solicitors. The wife acted in person, although she has occasionally consulted solicitors. In 2017 a judge dismissed the wife's application to set aside a consent order made in 2014. However, a person who was employed as a paralegal in the firm acting for the husband posted material to the judge earlier this year. Holman said he has not seen the material but understands it contains 'some account of things allegedly said between the husband, as client, and his solicitor (by whose firm the informant was employed) and junior counsel during the course of 2017'.

In February the judge recused herself from the case because she had seen the information which, the husband submitted, is protected by legal professional privilege. In the latest hearing, Holman decided to direct the case to the president for several reasons. As well as not having all the necessary official court transcripts he required, the judge said he did not feel sufficiently informed about the relevant legal framework and that 'quite intense consideration' may need to be given to the law on legal professional privilege.

Holman proposed listing the case before the family division president later this year to decide whether the information disclosed by the paralegal should be admitted into evidence.

Holman acknowledged that the law is familiar with privileged documents being inadvertently or accidentally supplied to another party, but said the wife possessed the material because it was deliberately sent to her by the judge.

Holman said: 'We live in an era in which so-called "whistleblowing" is less frowned upon than it once was and in which, indeed, in many circumstances whistleblowing is now encouraged'. However, he added: 'It is not difficult to see that if some employee of a firm of a solicitors can disclose what is otherwise prima facie privileged material, whether to the court or to the other side, the whole edifice of legal professional privilege might rapidly crumble.

'On the other hand, fraud is fraud, and my current understanding is that legal professional privilege cannot, in the end, withstand the unravelling of fraud or similar malpractices if (I stress if) they have taken place.'

51 Readers' comments