Is being an ‘activist lawyer’ a duty or a choice? Eduardo Reyes hears a call to arms from Paul Boateng

Born

Hackney, London 1951

Education

Accra Academy, Ghana

Apsley Grammar School, Hemel Hempstead

University of Bristol

Career

Solicitor, Paddington Law Centre (1976‑79)

Solicitor, then partner, BM Birnberg & Co (1979-87)

Member, Greater London Council (1981-86)

Member of parliament, Brent South (1987‑2005)

Government minister: Department of Health; Home Office; Treasury (1997‑2002)

Cabinet minister: chief secretary to the Treasury (2002-2005)

UK high commissioner to South Africa (2005-2009)

House of Lords (2010-present)

Known for

First Black member of the UK cabinet

‘My father was taken away.’

Paul Boateng is recalling the immediate aftermath of the 1966 CIA-backed coup against Ghana’s first president, Dr Kwame Nkrumah. Kwaku Boateng – barrister and cabinet member – was imprisoned without trial for four years. With his mother and sister, Boateng, then 15, fled to the UK. ‘We left at gunpoint with two suitcases.’

Boateng implies that the experience coloured the way he has approached the question of important choices in professional and public life.

‘Our role as lawyers,’ he continues, ‘is to decide – are we going to range ourselves alongside the powerless and dispossessed, and causes that require powerful institutions to be challenged? It’s not an easy choice, but you will have to make it.’

His audience this Tuesday evening in October comprises law students at London South Bank University (LSBU). It is not the average careers pep talk. But then Baron Boateng of Akyem in the Republic of Ghana and of Wembley in the London Borough of Brent has not had an average life.

Born in Hackney, Paul Boateng went with his family back to his father’s home country Ghana when he was four years old, ahead of independence from British colonial rule.

Returning to the UK once more from a life at the centre of the heady but turbulent reality of a post-colonial African nation, he then found himself in Hertfordshire. ‘I was the only Black boy at my school in Hemel Hempstead, and on the council estate where we lived,’ he recalls.

Such exceptionalism had consequences in 1960s Britain. He recalls walking home two days after Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, when a man in a van yelled ‘N*****s out!’ at the passing schoolboy.

‘I had to earn money as quickly as possible, and respond to the times,’ he recalls. ‘The Vietnam War loomed large. The threat of nuclear war loomed large. The Apartheid regime was entrenched in South Africa.’

This is why the law, for Boateng, does not float above the fray. ‘The rule of law is important. Access to justice is important,’ he says. ‘We as lawyers, as members of the legal family who have chosen law… The most important thing is activism. You are nothing in this world unless you choose to be active and to be an activist.’

After Boateng read law at Bristol University, he was articled to Benedict Birnberg, whose civil rights practice had cases at the front lines of issues that engaged the young aspiring lawyer.

The firm was a crucible for a generation of radical civil rights lawyers including Boateng, Gareth Peirce and Imran Khan. (See box, p22.)

‘It was a time of conflict with those who had power and privilege and wanted to keep it,’ he says. The flash points were conflicts over ‘race, sex, sexuality’, as well as housing and domestic violence.

'The law was about making the chance for something better – housing, social welfare, gender and social justice. For me, these early experiences confirmed my view – if you exclude people from access to justice, then you exclude them from the welfare state and its opportunities'

Boateng’s early work at law centres and at the firm included advising tenants who were in dispute with landlords. Being able to use laws such as the Public Health Act to secure clients’ rights and thereby ‘give them confidence that the law had some power’, he says, ‘set me on a particular path’.

Although he later qualified as a barrister, it was the existence of law centres that initially led Boateng to choose the solicitor profession. ‘That’s why I wanted to be a solicitor – to work in a law centre,’ he says. ‘Direct access rules prevented barristers – there was no dispensation.

‘At least we had legal aid,’ he reflects, though money was always tight at the practice. In addition, ‘Ben [Birnberg] was never a great one for billing,’ he recalls. The firm could not afford bailiffs to serve in (not least) cases of domestic violence, an area in which partner Judith Walker specialised.

As a result, Boateng says, he can ‘tell you the greatest, quickest get-away routes’ on the housing estates to which he was sent. ‘You served on a wife-beater. Then you had to leg it.

‘I learned how desperate life was for so many – and how domestic violence compounds it,’ he observes. ‘The law was a way of creating safe spaces. The law was about… making the chance for something better – housing, social welfare, gender and social justice. For me, these early experiences confirmed my view – if you exclude people from access to justice, then you exclude them from the welfare state and its opportunities.’

Boateng says: ‘It was a privilege to be articled to Benedict and to begin with Judith Walker. I worked with a young pupil barrister, Helena Kennedy. Me with an afro, her in an Afghan coat.’ Boateng and Kennedy are now peers: ‘If you’d told us where we’d end up!’

During 1977-81 Boateng was legal adviser to the ‘Scrap SUS’ campaign. The suspected person (SUS) law permitted police to stop, search and potentially arrest people on suspicion of breaching the Vagrancy Act 1824. The ability to arrest on suspicion of intent was widely misused and associated with racial profiling by the police.

Boateng’s experience of the campaign leads him to observe: ‘No one party has a monopoly over racism and sexism.’ Labour home secretary Merlyn Rees, he recalls, stonewalled attempts to repeal the legislation. In fact, the campaign got a more sympathetic hearing from the Conservative chair of the home affairs select committee, Sir John Wheeler, ‘who saw the iniquity of the SUS law’. The law was eventually repealed by the Conservatives.

Despite the radical strain to Boateng’s professional and political life, he draws a distinction between the two: ‘Law’s my profession and my career, and I have a political vocation. With politics, you feel called to it.’

That calling took him, in 1981, to the Greater London Council (GLC), then led by Ken Livingstone. Representing Walthamstow, Boateng chaired the GLC’s police committee and was vice chair of its ethnic minorities committee. He stood unsuccessfully for Hertfordshire West at the 1983 general election (the seat included Hemel Hempstead), then, in 1987, he was returned for Brent South. Also elected as MPs in 1987 were Bernie Grant, Diane Abbott and Keith Vaz.

Boateng was not done with law, however, qualifying as a barrister and continuing to practise while an MP. He was not alone on the Labour benches in doing so. Future Labour leader John Smith MP, who died in 1994, continued his practice until he was promoted to shadow chancellor.

Smith advised Boateng: ‘I’ve always done the odd murder – it’s a way of keeping your feet on the ground.’

In opposition he shadowed the Lord Chancellor’s Department, though as he rose up the ministerial ranks, minister of state at the Home Office was the closest he came to legal policy. As chief secretary to the Treasury, appointed in 2002, he was the UK’s first Black cabinet minister. He stood down at the 2005 general election, and was appointed UK high commissioner to South Africa.

But while Boateng’s identity in government was firmly centrist, he did not align completely with the New Labour project. He now says, with obvious regret: ‘Had John [Smith] lived, our country would be very different today.’

Days after Boateng’s visit to the LSBU’s lecture theatre, Labour won two parliamentary by-elections on swings of historical significance, apparently putting his party on course to win a huge majority at the next general election.

If Sir Keir Starmer arrives at 10 Downing Street as prime minister, Boateng is clear that addressing access to justice needs to be much higher up the party’s agenda than it currently is.

‘What has happened to legal aid is such a travesty,’ Boateng says. ‘Any incoming government has to see it as [key to] the welfare state. It’s as important as the NHS – as important as welfare benefits.’

Boateng is now co-chair of the Grenfell Tower Memorial Commission. The Grenfell tragedy occurred, he says, ‘because people in social housing don’t have a voice.

‘Legal aid is a shadow of what it was,’ Boateng concludes. ‘Miscarriages of justice occur every day as a result. Access to justice is a demand we have to make.’

Boateng’s choice of language when talking of the law seems to jar with the assertion that lawyers have a neutral role in doing a professional job for clients, with whom they should not be associated. The divide, of course, is not as stark as that. Birnberg’s firm, where he cut his teeth, represented what the principal referred to as ‘unfashionable’ clients, one of whom was ‘Moors Murderer’ Ian Brady.

But for aspiring lawyers who answer the call Boateng urges on them, the commitment required is clear: ‘You need to put yourself at the heart of a community’s struggle, at the heart of people’s struggles.’

For more information on the LSBU’s law department click here; or contact professor Sarah Chandler (sara.chandler@lsbu.ac.uk)

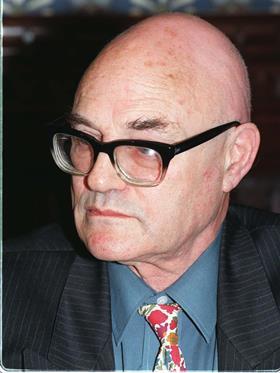

Benedict Birnberg: Activist lawyer

Solicitor Benedict Birnberg (right) died earlier this month, aged 93. His legal aid firm, BM Birnberg & Co (now Birnberg Peirce), then in south London, was a crucible forging radical lawyers acting for civil rights clients. Paul Boateng, Gareth Peirce and Imran Khan KC trained at the firm.

In the 1970s, partner Judith Walker paved the way for a more effective use of the law in domestic abuse cases. Tess Gill, who with journalist Anna Coote brought the 1983 sex discrimination case against El Vino wine bar, which refused women service at the bar, was another partner.

As for the community the firm had based itself in, Boateng says: ‘Borough High Street then was not as it is now. It was not a place to pay £7.50 for an artisan sausage roll.’

Writing in the Guardian in 2010, Boateng recalled: ‘To work with Ben Birnberg was to occupy a world in which the clients were varied and the causes mixed and not always popular. Birnberg had begun his civil liberties work with CND and represented Equity in its internal battles over the boycott of South Africa. The Redgraves were frequently in the office, as were numerous ANC luminaries. He fought for gay rights before the term was invented, representing the Albany Trust. He struck a blow for artistic freedom, defending David Hockney’s right to bring back magazines deemed obscene by customs and excise.’

1 Reader's comment