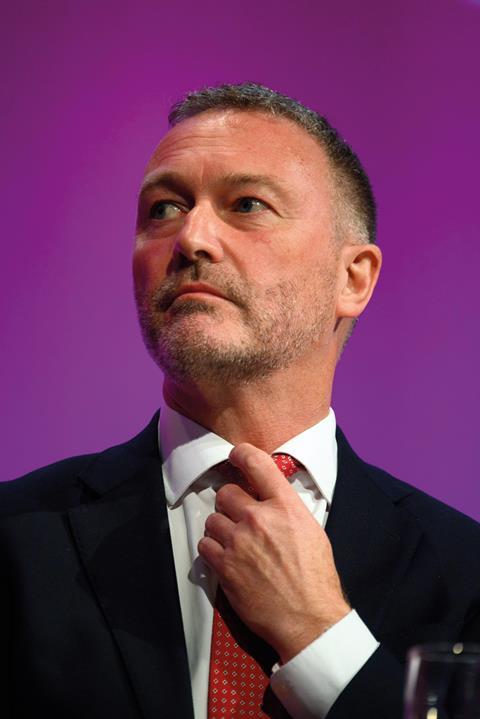

Sorting out crime and justice is one of Keir Starmer’s five ‘missions’ as Labour leader, but shadow lord chancellor Steve Reed won’t commit to pumping in new money. Catherine Baksi spoke to him

BIOG

BORN

1963, St Albans, Hertfordshire

EDUCATION

1974-1981, Verulam School, St Albans

1983-1986, English degree at the University of Sheffield, followed by an MA

ROLES

Publishing posts at Routledge, Thomson International, the Law Society and Sweet & Maxwell (1991-2002)

Leader of Lambeth Council (2006-2012)

MP for Croydon North since 2012

Shadow minister for children and families (June 2019-April 2020)

Shadow secretary of state for communities and local government (April 2020-November 2021)

KNOWN FOR

Appointed shadow lord chancellor and secretary of state for justice, November 2021

‘Whenever people tell me [politics] doesn’t make a difference,’ Steve Reed MP says, pointing to his finger, ‘I show them my wedding ring.’ Reed, 59, married his social worker partner of 14 years last July. That he was able to do so, he says, demonstrates the power of politics.

With the Labour party enjoying a large and consistent lead in opinion polls, the party looks set to win the next general election. And if he keeps his shadow role, Reed will become the first openly gay lord chancellor and secretary of state for justice.

Born and raised in St Albans, Hertfordshire, Reed’s parents and several other family members worked at Odhams printing factory in Watford until it closed in 1983, just as Reed was heading off to university.

His father got a job far from home before stopping work, leaving his mother with four jobs to pay the mortgage. They were Labour supporters, and he recalls his mother saying: ‘Thatcher’s taken your dad’s job, but she’s not getting our house.’

The late 1980s found Reed demonstrating outside parliament against Section 28 – the law passed by Margaret Thatcher’s government banning the promotion of homosexuality by local authorities and teaching in schools of what the law referred to as ‘pretended family relationships’.

Reed says his career in politics ‘kind of just happened’. A Labour party member at 16, he got involved in local campaigning after buying his first home in Brixton, in the south London borough of Lambeth, and responding to a request to distribute leaflets.

He was put in charge of organising Labour’s campaign in Brixton for the 1997 general election, the year of Tony Blair’s landslide. ‘I felt like a little tiny cog in a machine that helped that to happen,’ says Reed, whose exhilaration is palpable as he recalls the events of more than 25 years ago.

Elected to Lambeth Council the following year, he says his political education ‘began on the streets of Lambeth’, where he ‘learned more about politics than at any other point in my life’. He rose to become council leader in 2006, serving in the post for six years.

Elected as MP for Croydon North in 2012, Reed’s first parliamentary speech was a debate on the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act, which introduced civil marriage for same-sex couples in England and Wales. It was also the first bill he voted on.

Justice brief

Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer KC, a barrister and former director of public prosecutions, has not looked to his old profession to fill the justice brief. Reed is not a lawyer, though he considered the postgraduate law conversion course. But with an English degree from Sheffield University, he concluded that ‘I didn’t have the right background for it’.

He toyed with accountancy before entering publishing. Reed worked for three years as head of publishing at the Law Society, where he says he turned around a loss-making operation into one turning over more than £1m a year.

Since the last Labour government stripped back the ancient constitutional role of lord chancellor so that its holder is no longer the head of the judiciary, Reed sees the position as akin to any other ministerial job.

‘In the same way that the secretary of state for health doesn’t need to be a doctor, the secretary of state for justice doesn’t need to be a lawyer,’ he reasons. Reed says that he brings to the role ‘the perspective of the public as consumers of justice who want to live in a safer society’.

Thirteen years of Conservative rule has created a justice system that is ‘broken from end to end,’ he says. He points to the loss of 21,000 police officers, ‘abysmally low’ prosecution rates – 1% for rape, 4% for burglary and 6% for robbery – overcrowded prisons and probation ‘in freefall’.

Reed insists that crime and justice is an ‘absolute top priority’ for Starmer’s five-point ‘mission-led’ government, ranking second after the economy – and alongside the NHS, the climate crisis and education.

In his first speech setting out Labour’s justice stall, at Middle Temple last month, Reed said: ‘I’m not here to serve the legal profession, but to ensure our justice system always serves the public interest.’

Putting an updated spin on Blair’s slogan ‘tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime’, Reed says he will ‘prevent crime, punish criminals and protect communities’.

To address a key priority of tackling violence against women and girls, Reed pledged to speed up justice for rape survivors by opening specialist courts across the country and prioritising cases.

Tackling the backlog of more than 60,000 cases in the Crown courts and over 300,000 in the magistrates’ courts, Labour would increase the number of Crown prosecutors and train associate prosecutors to present cases in court.

But Reed admits: ‘There’s nothing I can do about the shortage of [criminal defence] barristers in the short term.’

He rules out reducing trial by jury and says he is not in favour of extending magistrates’ sentencing powers to 12 months.

'I’m not here to serve the legal profession, but to ensure our justice system always serves the public interest'

Drawing inspiration from overseas, Reed is keen to explore the idea of informal justice centres or community courts that operate as a diversionary mechanism for low-level offences and anti-social behaviour.

Where young people admit offending, the general principle, he explains, is to take a form of authority that they respect, such as a social or youth worker, teacher or faith leader, to chair a panel of professionals who provide a package of ‘sanction and support’.

The pre-charge disposal would not appear on a criminal record and, says Reed, where these centres operate they have reduced reoffending by 25%.

As a Lambeth councillor, Reed commissioned research into the causes of violent youth crime. This led to the first public health approach to tackling the problem, reducing offences by a third in 18 months.

Reed also wants to create the world’s first trauma-informed criminal justice system, applying medical understanding of the impact that abuse and neglect can have on cognitive and emotional development, to tackle the reasons for offending.

Prime minister Rishi Sunak’s focus earlier this week on tackling graffiti and fly-tipping, and getting offenders to clean up both, may sound familiar. Reed had already announced that Labour will introduce tougher penalties for fly-tipping and make offenders clear up rubbish, remove graffiti and rectify vandalism. He would also expand the use of parenting orders for parents whose children persistently offend.

So in terms of political positioning, is all that separates Reed and Sunak the latter’s preoccupation with banning ‘laughing gas’?

Reed responds that a Labour government would respect the rule of law, and protect and promote the Human Rights Act and the European Convention on Human Rights.

For the record

While a member of Lambeth Council, Reed introduced a scheme to ‘name and shame’ those convicted of buying or selling recreational drugs in the borough. In a recent BBC interview, he said that he smoked cannabis once but ‘didn’t like it’.

He launched the country’s first cooperative council model that tried to deliver better services more cost-effectively by giving more control to residents. The idea was based on his experience of working with the residents of Blenheim Gardens in Brixton, who transformed their estate by forming a resident management organisation.

In 2010, Reed was reported to the standards board by a Conservative councillor after disclosing that she was barred from voting on financial matters because of her refusal to pay council tax on one of her properties. The information was legally disclosable and he was not sanctioned.

As council leader, he turned around Lambeth’s poorly performing children’s services, which led to them being rated ‘outstanding’ by Ofsted in 2012, drove down gang violence and drug offences in the borough, and in 2013 received an OBE for services to local government.

In 2016 he resigned as shadow minister for local government as part of the so-called ‘chicken coup’ mass action by the shadow cabinet against Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. He supported Owen Smith’s failed bid in the subsequent leadership election.

Reed apologised ‘unreservedly’ in 2020 for a tweet calling Tory party donor Richard Desmond a ‘puppet-master’ in what critics said was an antisemitic trope.

Money matters

The shadow justice secretary is, though, silent on additional funding – arguably the single measure that would most improve the cash-starved justice system, which suffered 40% cuts in the decade from 2010/11.

On criminal legal aid, Labour has pledged to implement in full the recommendations of the Bellamy review, which called for an immediate 15% fee rise for barristers and solicitors. Reed stands by that pledge, which could be good news for solicitors, who were actually handed just 9%, prompting a legal challenge by the Law Society.

But he cannot commit to building on Bellamy by increasing fees further. Reed says that the many demands on the public purse will mean that increasing legal aid ‘will have to wait until Labour’s grown the economy’.

Any funding decisions must wait until the conclusion of Labour’s ‘end-to-end review’ of the criminal justice system and go through the national policy forum. ‘We can’t start making policy on the hoof,’ he insists, arguing that proposals have to be ‘fully funded, robust and clear’.

In his Middle Temple speech Reed pledged Labour’s commitment ‘to ensure that everyone has equal access to justice irrespective of means’.

'Increasing legal aid will have to wait until Labour’s grown the economy'

But, fresh from a meeting with representative groups and with a pile of reports on his desk in Portcullis House, topped by Legal Action Group’s Legal Aid Matters publication, Reed cannot say whether Labour will restore public funding for any of the areas of civil practice that were removed by the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012.

Rather, he says: ‘We are trying to look at a different model for legal aid’, because the system that we have now, premised on ‘higher resource’, does not work.

Despite a desire to ‘halt the slide to unaffordable civil justice’, and suggesting that lawyers’ fees are too high, Reed will not reveal any specific proposals here.

Instead, his plans to make justice ‘more accessible’ to those who cannot afford it include greater use of technology and online advice. He is also looking to the City for an increased commitment to pro bono, telling lawyers in global firms that they must ‘do more to help those who have been left behind’.

Reed rules out mandatory pro bono targets, which predecessor David Lammy proposed at Labour’s 2021 party conference. And he is non-committal about a levy on City law firm profits to help fund legal aid – mooted by former Conservative justice secretary Michael Gove – stating: ‘I won’t say now what I will or won’t support.’

Keen to improve judicial diversity, Reed wants to extend ‘non-traditional routes’ to draw applications from employed barristers and legal executives, and identify barriers to retention of women and lawyers from ethnic minority backgrounds. His speech pledged that ‘Labour will implement all remaining recommendations of the Lammy Review’, which addressed racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

On the controversial issue of trans prisoners, he says Labour’s ‘overriding priority is the protection of women’. Therefore, he ‘does not envisage’ trans women prisoners being admitted to women’s jails, as happened in the case of Isla Bryson in Scotland.

Reed is not, though, a fan of one of Lammy’s key recommendations – national targets to increase judicial diversity. He fears that targets can create perverse outcomes: ‘My gut feeling is that targets may not be the right way to go.’

Catherine Baksi is a freelance journalist

No comments yet