Embodiment and the Law: A New Approach to Analysis, Discourse and Reasoning

Samuel Walker

£90, Edward Elgar Publishing

★★★★✩

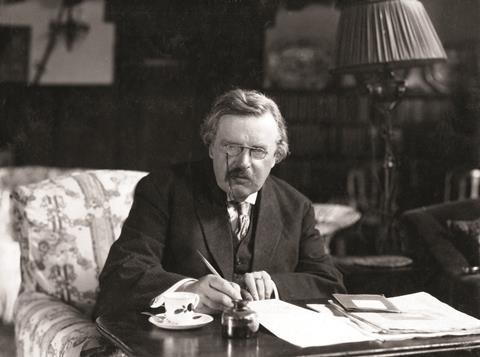

G K Chesterton, rotund spinner of ecclesiastical detective yarns and unapologetic apologist for tradition and faith, was a frequent critic of change. Writing about changes to significant social institutions, he used the analogy of a fence built across a road at some time in the past: ‘The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away”. To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.’”

We’ll return to Chesterton’s fence shortly.

In this work, Walker argues that the law fails to engage with ‘embodiment’, with negative impacts on the development of normative principles. Embodiment is, essentially, a concept that requires considering ‘the totality of our lived experience; from gestures to clothing, from physical spaces we inhabit to information about ourselves; from our internal sense of self to the attitudes and behaviours to which we are subjected by others’.

He argues that where the law affects individuals as physical entities – in areas as diverse as dress codes, medicine, information rights, and body modification – the values informing the principles treat the physical body as an abstract concept, which prevents a full consideration of the impacts of the law on the individual.

The argument is fascinating and the claim that the concept of embodiment would change how certain aspects of law are adjudicated has merit. However, stripped down, Walker’s argument seems to be that the law should maximise individual autonomy as the highest good. As a result, the argument goes to the heart of a key issue about the role of law in society: whether the role of law is to protect the liberty – or possibly simply the autonomy – of the individual, contrasted with law being a tool for promoting the common good and human flourishing.

This is illustrated with one of the more extreme examples cited – body modification. Walker considers in detail the Court of Appeal decision in R v BM (2018), in which it upheld the conviction of a tattooist for wounding under the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 after the tattooist performed extreme body modification procedures, including cropping ears, removing nipples and splitting tongues to create a reptilian fork shape. The court reaffirmed the general rule that consent was not a defence to wounding, holding that body modification did not fall within the exceptions to that rule (broadly, that the procedure may produce discernible social benefit; and it would be regarded as unreasonable for common law to criminalise).

In the ‘embodiment’ analysis, Walker argues that the law should and would permit an individual wishing to split their tongue, or remove a healthy body part, if that is their autonomous – and presumably capacitous and informed – decision. In contrast, an approach that emphasises the common good would adopt some form of the current position. It would not be beneficial to the common good or to human flourishing to permit individuals to consent to irreversible procedures on their bodies for aesthetic reasons – or for no reasons at all – where there is no medically recognised physical or psychological benefit. While BM is an unusual case, it illustrates well the outer edges of the argument.

And this brings us back to Chesterton’s fence. There is something of the zealous fence-remover about the ‘embodiment’ argument; at times, Walker’s argument seems close to claiming that current legal norms surrounding the body are no longer fit for purpose or are merely discriminatory. A more cautious assessment might consider that the norms the argument opposes are there for a reason. Perhaps the law has deliberately chosen to protect the vulnerable and prevent people from causing irreparable physical harm to themselves, not out of some absence of mind or indirect discriminatory purpose, but because the ultimate functions of the law and society are best achieved by restricting the individual’s autonomy in certain cases. We should remember the purpose of the fence before we try to remove it.

Overall, this work is worthwhile reading for those interested in legal philosophy and ethics.

James E Hurford is a solicitor at the Government Legal Department, London

No comments yet