Majority support for some form of regulation, the use of AI and the risk of acting in high-profile cases are among the key takeaways from this year’s Bond Solon Expert Witness Survey

The lack of oversight and transparency pertaining to the use of expert witnesses in English courts continues to gain political traction. Earlier this year, former attorney general Dominic Grieve and former justice secretary Jack Straw called for a system of regulation. They warned that criminal and civil trials sometimes hang on evidence by self-appointed ‘experts’ who may lack the necessary knowledge and impartiality.

The issue had returned to prominence amid questions about potential miscarriages of justice following the use of experts in the Lucy Letby and Post Office Horizon cases. Westminster remains deeply concerned. Just last week, cleared ex-City trader Tom Hayes told the All Party Parliamentary Group on Miscarriages of Justice that juries should be told how much an expert is being paid and how many times they have appeared for either party.

Hayes, whose LIBOR rate-rigging convictions were quashed by the Supreme Court earlier this year, also lamented ‘a complete inequality of arms in relation to experts’ at his trial. While Hayes had none, the prosecution had two, one of who gave ‘extremely damning testimony’.

In one important respect, those advocating greater formal oversight of expert witnesses appear to be pushing at an open door. That is one conclusion to be drawn from this year’s Bond Solon Expert Witness Survey, produced in conjunction with the Gazette and published to coincide with today’s Bond Solon Expert Witness Conference.

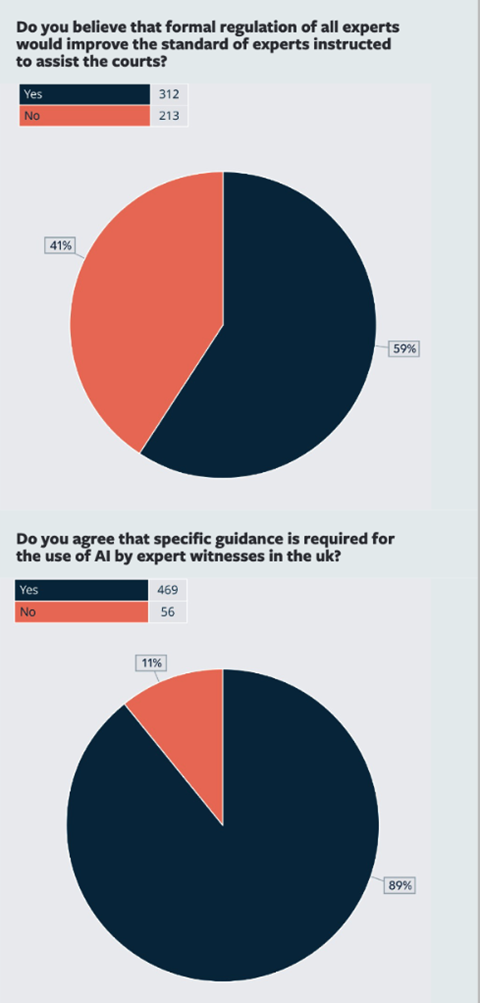

More than half (59%) of 525 experts surveyed believe that formal regulation of all experts would improve standards. As the report notes, this was brought into sharper focus in March when the Family Procedure Rule Committee consulted on plans to require any expert instructed in family law children proceedings to be regulated. ‘This is relatively straightforward in professions such as medicine or psychology, where some categories of psychologist are regulated, but more impractical in professions without a regulatory body,’ Bond Solon’s report says.

Two-thirds of the experts canvassed this year work in the medical/healthcare sector. The rest range across disciplines as diverse as SEND tribunals, creative arts therapies, terrorism and extremism, and even sport.

So what do the majority in favour of regulation want? Many felt that a regulatory or training body for experts would be helpful, or suggested a government register of accredited experts. Several favoured a mandatory examination on Civil Procedure Rule (CPR) 35, which governs the use of evidence from experts and assessors in civil proceedings. Others recommended a minimum level of continuing professionadevelopment to be undertaken each year.

‘As always,’ the report adds, ‘the sticking point will be cost. Instructing solicitors already use due diligence in the selection and instruction of experts, and courts have considerable influence as to what expert evidence can be used.’

If formal regulation were to be introduced, 71% of respondents backed mandatory training and assessment as part of the oversight process.

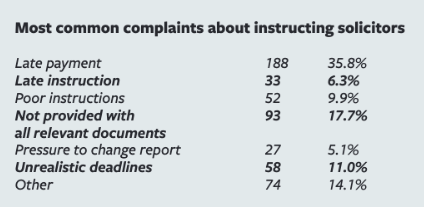

This year’s survey once again quizzed experts about their relationship with solicitors. Late payment is a perennial bugbear, with over one in three (188) citing this as their most common complaint. Not being provided with all relevant documents (93), unrealistic deadlines (58) and poor instructions (52) ranked next on the list.

There have been pleas for the Solicitors Regulation Authority to introduce specific regulations to improve the professional relationship between experts and solicitors, but these have gone unheeded. Speaking at last year’s Expert Witness Conference, chief executive Paul Philip urged experts to call out unethical conduct, but stopped short of committing to a new process for experts to report solicitors to the regulator.

If the expert has exhausted the solicitor firm’s internal complaints process, said Philip, their next ‘port of call’ is the legal ombudsman. Non-payment of fees may well be a regulatory matter, he admitted, but only if it is serious, there is a lot of money involved, or it is persistent.

In short, the problem would seem to be intractable.

As for pay rates, these seem to have risen very modestly over the past decade – at least for civil practitioners. Experts in this sector reported an average hourly rate for report writing of £239, a 25% rise on Bond Solon’s 2015 survey. The average hourly rate for those working in the criminal courts is £227, a 55% rise since 2015, and £210 in family, a 48% rise. Bond Solon warns that these comparators should be treated with caution, however, as they are not based on the same subject sample and volume of data.

A principal focus of this year’s survey is the use of artificial intelligence by expert witnesses. AI cannot really be said to have caught on yet. The proportion of experts who use it has doubled from last year, to 20%, but this is considerably lower than usage elsewhere. According to KPMG’s UK attitudes to AI study, 65% of workers in the UK intentionally use AI for work.

‘The reticence among expert witnesses to use AI likely reflects the fact they are not yet confident about how and when it may be appropriate to do so,’ says Bond Solon’s report. ‘On 6 June, the president of the King’s Bench Division of the High Court, Dame Victoria Sharp, said: “There are serious implications for the administration of justice and public confidence in the justice system if artificial intelligence is misused.”’ If an expert chooses to use AI technology in the construction of their report, ‘it is vital that they double-check the material produced by AI to determine the accuracy of the information. Incorrect information will open the expert up to criticism and potentially impact the outcome of a case’.

The one in five experts who had deployed AI had generally done so to assist with research. This included using Google, which is AI-assisted, or large language models such as ChatGPT to find and summarise information. Others said they used AI to rephrase writing, check grammar and spelling, or to calculate results from data. One respondent even said they used ChatGPT to challenge their professional judgement. ‘I have used ChatGPT Plus as a debating board – a tool for challenging my own opinions, and for germinating ideas. I have not used it for content creation,’ they explained.

A large majority of respondents (89%) pointed to the need for specific guidance on the use of AI by experts. Dame Victoria Sharp’s criticism referred to two cases in which fake authorities were cited in evidence before the court due to careless use of AI. ‘There are also cases from other jurisdictions, such as the American case, Kohls v Ellison No 24-cv-3754 (D Minn 10 January 2025), in which an expert witness used generative artificial intelligence to draft his report and accidentally submitted misinformation,’ Bond Solon’s report adds. ‘Ironically, he had been instructed as an expert on AI-generated deepfakes! Perhaps this is the time for strong guidance from the judiciary in terms of court rules, protocols and case law dealing with AI.’

Bond Solon founder Mark Solon said: ‘There are several areas where experts may be at risk if they use AI, including the accuracy of data and data privacy. Experts must ensure that they use reputable platforms and are aware of the security risks. Everything received from AI must be checked and the final report must be in their own words. It is crucial that the courts provide further guidance on the use of AI and the risks involved of misuse.’

Elsewhere, the survey covers the perceived risks of acting as an expert in high-profile cases. The potential personal and reputational pitfalls have been starkly demonstrated in recent months by the fierce criticism directed at the lead prosecution expert in the Letby case, retired consultant paediatrician Dewi Evans.

More than one respondent reported having turned down high-profile murder cases for fear that the media attention could interfere with family life. Another said they had refused ‘some criminal work for defence where there seems a strong likelihood of guilt’. Others cited being on the end of judicial criticism, which left them more cautious about what work to take on.

Such reticence is surely understandable. No one wants to be exposed to the media’s withering gaze, but it can and does happen.

No comments yet