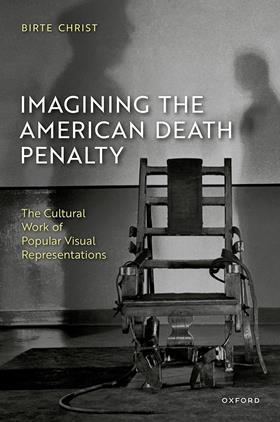

Imagining the American Death Penalty: The Cultural Work of Popular Visual Representations

Birte Christ

£88, Oxford University Press

★★★★✩

There is a familiar scene in many US prison movies. A prisoner with a shaved head is led in chains along a dimly lit corridor, past silent inmates, to a small room containing a large wooden chair. The chair, illuminated by a single light bulb, is arrayed with leather straps and electric power cables and a tall, severe man stands alongside. Death sentences and executions are an enduring part of American folklore.

Imagining the American Death Penalty tells how capital punishment has been represented, on film and later on TV, from the 1890s to the 21st century. Birte Christ explains that popular media interest in the death penalty does not necessarily equate to support for abolition, as the moral position of the filmmaker can be ambiguous and dependent on the political mood of the time. She also explains why the condemned man is often portrayed as a defiant hero who gains dignity as he accepts his lethal fate.

Film noir cinema of the 1950s and 1960s focused on guilty men, which went hand in hand with a public debate that was not interested in innocent convictions, but on the possible rehabilitation of criminals. This reflected a growing loss of popular support for capital punishment. Furman v Georgia (1972) was a landmark criminal case in which the US Supreme Court decided that arbitrary and inconsistent imposition of the death penalty violates the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments, and constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. Although the justices did not rule that the death penalty was unconstitutional, the Furman decision invalidated the death sentences of nearly 700 people. The case resulted in a de facto moratorium on capital punishment throughout the US. There followed a backlash, and public support for the death penalty increased dramatically. Dozens of states rewrote their death penalty laws. The decision of the Supreme Court in Gregg v Georgia (1976) reaffirmed the court’s acceptance of the use of the death penalty and essentially ended the moratorium. The first execution since 1968 was carried out in 1977 when Gary Gilmore waived all appeals and was executed by firing squad.

According to the author, ‘the earliest execution films produced between 1895 and 1905 show white victims of the death penalty. The absence of black persons in these execution scenes… ennobles the death penalty by visualising it as white in the American imagination’.

In the author’s study of 32 ‘death penalty’ films produced between 1951 and 1968, only three films (including To Kill A Mockingbird) feature non-white defendants in capital cases. In each film, the stories are not told from the perspective of the non-white defendant and, unlike many of the films that portray white defendants, they are not granted a heroic or redemptive narrative. By contrast, in The Green Mile (1999) and True Crime (1999), the black prisoners on death row are afforded some measure of individualism, humanity and agency. But, ultimately, both films revolve around white heroes and the expiation of ‘white demons’.

Christ tells us there are more than 1.9 million people imprisoned in the US. While the death row population has been steadily declining for the past 20 years, the rate of prisoners serving life sentences has been continuously rising. ‘Life without the possibility of parole’ has been called ‘America’s New Death Penalty’. After a 17-year hiatus in federal executions, the first Trump administration (2016-2020) executed 13 men on federal death row, illustrating clearly the role of the death penalty as a token in the culture wars. A politician’s position on capital punishment acts as a shorthand for where they stand across a great number of social issues, including race relations.

This is an engaging book that challenges the reader to confront their own assumptions and preconceptions about the death penalty.

Kevin McVeigh is a partner at Elliott Duffy Garrett Solicitors, Belfast

No comments yet