With exclusive access to a public observers’ report on criminal justice, Catherine Baksi reviews government efforts to balance the connected crises in prisons and the courts

The low down

Criminal justice has been chronically underfunded for decades. That is no secret. But few members of the public see the daily reality. As the work of a justice reform charity reveals ‘shocking’ court delays, the government is taking steps to address the backlog of cases and prison overcrowding. Former justice secretary David Gauke’s recommendations to relieve the burden on the penal system have been taken up in a Sentencing Bill. But ministers are yet to respond to Lord Leveson’s proposals on the courts; his second review, looking at efficiency, is still awaited. One innovative problem-solving court appears to be having some beneficial impact – but will resourcing problems and low fees damage its prospects?

‘If the NHS ran like the courts, we’d all be dead!’ This was the bleak verdict on the impact of delays and inefficiency witnessed in the magistrates’ courts by a volunteer who took part in CourtWatch London, a project run by the charity Transform Justice.

Over six months this year, from 5 February to 31 July, 175 Londoners of all ages, backgrounds and boroughs took part in the second phase of a scheme designed to build awareness of the state of the courts.

Transform Justice seeks to use the evidence to advocate for a ‘fairer, more effective, more compassionate criminal justice system’.

Observing the magistrates

In the first round of CourtWatch London, which took place in 2023, 80 volunteers observed and reported on 1,100 magistrates’ court hearings in three London courts. This second round expanded to cover all 15 courts.

While much attention is paid to the record backlog of cases in the Crown courts, which stands at 78,329, the number waiting to be dealt with by magistrates – who deal with over 90% of criminal matters – is often ignored.

According to the most recent government statistics, published in September, the backlog in the magistrates’ courts stands at 361,027 – a record high. On average, it takes 206 days for a case to make its way through the magistrates’ court, from offence to case completion.

Of over 2,335 hearings observed by the courtwatchers, more than a third (37%) resulted in a delay or adjournment, according to a draft report seen exclusively by the Gazette. Those observers were ‘shocked’ by the inefficiency they witnessed.

Delays ranged from waiting 20 minutes for a lawyer to arrive, to a one-month adjournment for a pre-sentence report.

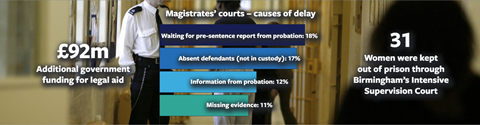

The most common reasons for delays or adjournments were waiting for a pre-sentence report from probation (18%) and defendants who were not in custody being absent (17%).

Being unable to proceed without more information from probation accounted for 12% of delays. Missing evidence caused 11%, followed by magistrates deliberating (8%), missing defence lawyers (8%), defence lawyers not being ready (7%) and the lack of an interpreter (5%).

Other delays were caused by problems with technology (4%), cases being moved to a different court (4%), defendants in prison not being brought to court on time (3%), the prosecution advocate not being present or ready (3%) and the previous case over-running (2%).

The courts with the highest proportion of delayed hearings were Westminster, Stratford and Bromley; the lowest were Barkingside, Lavender Hill and Willesden.

The courtwatchers noted the wide-ranging consequences of the delays. These range from increasing the anxiety of defendants, victims and witnesses, to heavy caseloads piling pressure on court staff, magistrates and advocates.

One observer branded the system as ‘chaotic and farcical’, while another said the delays were ‘bordering on abuse’ of defendants.

Despite their concerns over the time taken for cases to be dealt with, the courtwatchers do not always want the process to be speedier. They were concerned when matters felt ‘rushed’, because ‘this jeopardised a defendant’s right to a just and considered outcome’.

Where they felt that cases were being dealt with too quickly, one observer said ‘it felt like another conveyor-belt day, with people being rushed through their hearings, which sometimes lasted only around 10 minutes’. The courtwatcher added: ‘I wish the courts had more time to engage with each defendant, rather than sentence them or move their case on after only spending a few minutes with them.’

Watching a case concerning a defendant charged with possession of drugs with intent to supply, who was remanded into custody and his matter sent to the Crown court, another courtwatcher noted: ‘I was surprised by how quickly it was over. I think waiting for the defendant to be brought up to the courtroom took longer than the actual hearing.’ They were also concerned about the impact on the defendant’s tearful mother watching from the public gallery.

More positively, in some cases the courtwatchers said that they ‘appreciated judges or magistrates slowing down to carefully deliberate on an outcome, or to clearly explain the court process to unrepresented defendants’.

The observers questioned why so many defendants were not represented by a lawyer, noting that their cases necessarily took longer or had to be adjourned to enable them to get legal advice.

Ensuring defendants had access to legal advice, they suggested, would save court time and resources. They recommended making legal aid available to more defendants and abolishing the means test for all those charged with an imprisonable offence.

The courtwatchers suggest giving more support to unrepresented defendants, allowing them to access their case file online and increasing the number of duty solicitors. They were also frustrated by cases they felt could have been resolved out of court by the police, instead of ‘wasting’ court time and resources.

Intensive supervision courts

Since their creation in June 2023, the government has opened four Intensive Supervision Courts (ISCs). There are three substance misuse sites, at Bristol, Liverpool and Teesside Crown courts, and one women’s ISC at Birmingham Magistrates’ Court (pictured). Designed as part of the government’s £900m drug strategy, the problem-solving courts offer a tougher approach to community sentences for low-level criminals who would otherwise face short jail terms. They seek to turn offenders away from crime by tackling the underlying issues linked to their offending.

A 2024 evaluation report by the Ministry of Justice found that the ISCs were diverting offenders away from custody, helping to reduce drug and alcohol intake and giving them a sense of purpose and routine.

By the end of January 2024, 63 people had been sentenced by the courts. The report found ‘positive relationships’ had developed between the judges and individuals sentenced and ‘good engagement with order requirements’.

On the downside, the report highlighted the ‘lack of involvement of housing services’, heavier than expected workloads due to the high level of support needed by those sentenced and a lack of additional funding for partner organisations providing support.

Between July 2023 and January 2024, 31 women were kept out of prison because of the Birmingham ISC. The Criminal Justice Alliance charity has said the courts are a ‘positive step forward in a system that often does little to tackle the underlying reasons why women enter it in the first place’. It hailed the Birmingham ISC as a ‘brilliant example of what can happen when we are bold enough to move away from the status quo and try something new’.

The Law Society also supports this approach, but calls on the government to ‘take urgent action to amend legal aid regulations to ensure that solicitors are fairly remunerated for appearing at these courts’ – courts which, president Mark Evans explains, can have multiple additional hearings.

Addressing delays and a prisons crisis

In a bid to tackle the linked crises of overburdened courts and prison overcrowding, which had forced ministers to start releasing prisoners early, the last Conservative government commissioned retired Court of Appeal justice Lord Leveson to address the case backlog. The new Labour government picked up the baton by commissioning a second report, led by former Conservative lord chancellor David Gauke, focused on prisons.

Leveson reported in July, a year after the change of government, controversially recommending curbs on the right to trial by jury. He suggested that some defendants could opt for trial by judge alone and proposed dealing with some cases currently tried in the Crown court in a new intermediate court comprising a judge and two lay magistrates.

The Magistrates’ Association welcomed the proposed reforms, as long as they would be accompanied by a third more magistrates and additional staff to run the court.

Criminal solicitors are naturally keen for the delays to be addressed, given that cases are now being listed for as far away as 2030. But they are concerned about the reclassification of offences and the removal for some defendants of what Katy Hanson, president of the Criminal Law Solicitors’ Association (CLSA), regards as the ‘central tenet of the justice system that defendants are tried by their peers’.

Hanson suggests that if cases are not heard by a jury, there is ‘a lack of diversity in the judiciary in terms of socio-economic background and ethnicity that may well lead persons to feel that they are not receiving a fair hearing by their peers’.

Piers Desser, a solicitor at Carson Kaye and media advocate of the London CLSA, suggests that Leveson’s proposal to increase the use of out-of-court resolutions is ‘sensible’. But he warns that eroding the right to jury trial carries ‘serious dangers’ just to achieve a ‘short-term fix’.

Leveson’s proposals are ‘no silver bullet’, stresses Mark Evans, president of the Law Society. He reiterates the body’s call for ‘sustained investment’ in a criminal justice system that has been ‘starved of resources for decades and is now at breaking point’.

That means people as well as cash. ‘When the existing magistrates’ courts and Crown courts are already overwhelmed and under-resourced, where are the extra judges, magistrates, court staff and lawyers going to come from?’ he asks.

The government has yet to respond to Leveson formally. The Gazette understands that ministers are still considering his recommendations, including their impact on the prison population and the interaction with the reforms in the Sentencing Bill currently going through parliament. Those reforms are largely based on the Gauke review.

The second part of Leveson’s review, focused on efficiencies, is expected to be finalised by the end of the year.

Set up to fail?

Gauke’s 48 recommendations included: more community-based sentences; suspended sentences as an alternative to jail; a presumption against short sentences, with sentences of less than 12 months to be used in exceptional circumstances only; and a ‘progression model’ of early release for good behaviour.

The government incorporated much of this in the Sentencing Bill 2025. Reforms include making offenders, including those jailed for serious crimes, eligible for release after they have served a third of their sentence.

Some victims’ groups allege that the proposals will send the wrong message to offenders. Organisations working with prisoners are strongly in favour, while stressing the need for increased funding for the prison and probation services to reduce reoffending.

'After decades in which prison sentences have got longer and longer, our prisons are full and the projections show that it is not possible to build our way out of this crisis'

David Gauke

Andrea Coomber, chief executive of the Howard League for Penal Reform, warns that the government’s proposals for earned release ‘could be difficult to deliver at a time when prison regimes are impoverished and, consequently, drugs and violence are rife’. She adds: ‘We do not want to see people set up to fail and spending longer than necessary behind bars.’

Coomber also suggests that the government ‘risks setting people up to fail if probation does not receive the investment it needs to work effectively and responsively in the community’.

'Either serving prisoners get released early to make way for those due to be sentenced, or judges may be forced to more frequently use non-custodial options'

Danielle Reece-Greenhalgh, Corker Binning

Stressing the need for action, Gauke tells the Gazette: ‘After decades in which prison sentences have got longer and longer, our prisons are full and the projections show that it is not possible to build our way out of this crisis. Any government in these circumstances would have little choice but to make changes broadly along the lines that we recommended.’ The former lord chancellor is pleased that the government ‘is facing up to the challenge’.

Danielle Reece-Greenhalgh, a partner at Corker Binning, notes that ‘the government is stuck between a rock and a hard place’, adding: ‘Either serving prisoners get released early to make way for those due to be sentenced, or judges may be forced to more frequently use non-custodial options in cases where offenders otherwise would have expected to serve time.’

Prison overcrowding

Since the Court of Appeal in R v Ali [2023] EWCA Crim 232 confirmed that judges should be permitted to take prison overcrowding into consideration when sentencing offenders, Reece-Greenhalgh says many offenders now being sentenced to 12 months or under are already having those sentences suspended.

In the meantime, the government is continuing its predecessor’s policy of building more prisons, investing up to £7bn to add 14,000 new places and improve the estate.

In a bid to divert offenders away from crime, ministers are also expanding the use of Intensive Supervision Courts (see box, p18). These direct repeat offenders into mental health, drug or alcohol treatment programmes to address the root cause of their offending behaviour. Use of unpaid work orders is also increasing.

Professional decay

'We are now further than ever from the 15% increase recommended by the Bellamy review'

Katy Hanson, CLSA

More widely, solicitors highlight the effect on their profession of decades of underfunding. Most acutely, this is seen in the declining numbers of duty solicitors caused by poor legal aid rates.

Desser notes that in April 2022, there were 4,255 duty solicitors and 1,019 firms with duty solicitors attached to them. By April 2025, those figures had fallen to 3,916 and 942 respectively.

While the government has announced an additional £92m in legal aid funding, Hanson notes that solicitors have yet to hear when any increase will be implemented. ‘We are now further than ever from the 15% increase recommended by the Bellamy review,’ she laments, calling for annual index-linked increases to take inflation into account.

‘Criminal legal aid solicitors are the backbone of the criminal justice system and it is vital they are protected from becoming an extinct species,’ concludes the Law Society’s Evans, echoing Hanson’s plea.

Is Labour coming up with the right answers to the system’s manifold shortcomings? A government spokesperson tells the Gazette: ‘[We] inherited a justice system in crisis, with prisons on the brink of collapse and a huge court backlog meaning victims are waiting too long for their cases to be heard in court. This is why we are driving once-in-a-generation reforms to ensure our prisons never run out of space again and victims get the justice they deserve.’

Catherine Baksi is a freelance journalist

No comments yet