The Rule of Laws: A 4,000-year Quest to Order the World

Fernanda Pirie

£25, Profile Books

★★★★✩

The world’s earliest known laws were inscribed on to clay tablets, stones and bamboo strips. These emblems of authority constituted laws in their most rudimentary form, and perpetuated a legal tradition over thousands of years. Fernanda Pirie, professor of the anthropology of law at the University of Oxford, has divided her excellent survey into three parts – ‘Visions of Order’, ‘The Promise of Civilization’, and ‘Ordering the World’ – to convey the full impact of those nascent legal systems.

In unearthing that Mesopotamian king Ur-Namma imparted laws on to clay tablets, Pirie begins an absorbing journey. ‘Anyone could now quote a law,’ Pirie writes, ‘which had been pronounced by the king. It was the beginning, indeed, of the rule of law.’ As kings put down early legal roots – continued by Babylon’s Hammurabi whose laws were inscribed on to tall stones and reflected ‘a stratified society in which people followed distinct professions’ – it is striking how durable a king might expect those laws to be. Hammurabi called ‘down a series of terrifying curses on any future king who [did] not respect’ his laws. The nucleus of those laws – for example, Ur-Namma’s rules targeted wrongdoing and setting out just compensation – held out the promise of written rules that could regulate societies.

Pirie is excellent at explaining complex instruments of governance. Religious specialists (brahmins) were responsible for ‘laws crafted on the Indian plains’, pontificating on the cosmological order in ancient Sanskrit texts (Vedas). Here we learn about the ‘duties people had to fulfil if they were to uphold the dharma, the ideal order of the world’ and about ritual texts (Dharmasutras) that expressed ‘a sense of justice and right conduct’. Pirie also spells out what law meant to different societies. ‘While the Mesopotamian kings were mapping out social justice,’ she writes, ‘the brahmins were specifying individual duties with cosmological order in mind.’

Pirie uses summary to smoothly cover a span of history. In the section on ‘Chinese Emperors’, for example, Pirie writes: ‘The emperors never allowed a class of priests, or any other specialists, to challenge their authority as lawmakers… their vision of order was one of discipline and punishment’. The motif of law wrought on to objects again comes into play. In this case, bamboo strips were used to record cases, thereby establishing precedent, ‘not unlike the English common law’. And in succinctly closing this chapter, Pirie argues that the laws in Mesopotamia, India and China were not entwined; rather they ‘developed quite independently’.

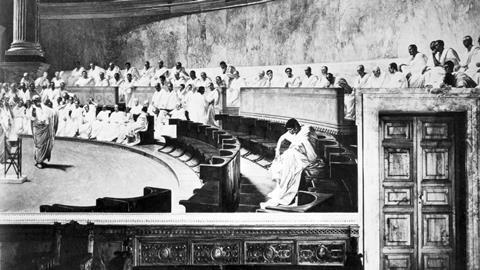

Pirie teases out a parallel between ancient Rome and Hammurabi. In ‘Advocates and Jurists’ (‘Intellectual Pursuits in Ancient Rome’), we learn that the Twelve Tables dealt with ‘disputes in the normal course of Roman life’. The ‘general principles that could be applied to a range of cases’, as set out in Hammurabi’s laws, also found resonance in the tables. Inscribed on bronze tablets, consuls agreed that the tables should be put up in the Forum. In several speeches, Cicero described the tables ‘as the source of Rome’s laws’.

Having seized power as First Consul in 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte was inspired by Rome, grounding his new civil code in Roman precedents. And like Justinian he thought he could ‘rule, godlike over his creation’. Pirie asserts that, ‘like the Roman emperor 13 centuries earlier, he was quick to brush aside academic arguments that any law could transcend the authority of the ruler’.

Pirie consistently presents seismic global changes as threads in the evolution of our modern laws. ‘The state laws that now dominate the world are largely based on those developed in European countries and America from the 17th century onwards,’ she writes. And at the start of the 20th century, with societies governed by the Mughals, the Ottomans and the Chinese Qing in abeyance, ‘in Europe, the system of states was more or less established, and the common and civil laws were being transplanted around the world’.

Piri’s writing is evocative throughout this superbly packaged history. As well as a striking cover, there is a feast of colour illustrations, including the laws of Anglo-Saxon king Athelstan; papyrus from the Roman census of Arabia in 127; an Icelandic book of laws from the 12th century; and a ‘15th-century copy of the Naradasmrti, a Dharmashastra text that concentrates on legal matters, made for the Himalayan Malla kings’.

Nicholas Goodman is a sub-editor at the Law Society Gazette

Escapement

William Kinread

£9.99, Fisher King Publishing

★★★★✩

There is an authentic 1980s feel to this legal thriller in which our lawyer hero travels across Europe on behalf of a client – as you do. The story involves former Nazis, the Vatican and Yorkshire. What more could you ask? You can tell the story is set decades ago as the solicitors make lots of money. Our hero drives an E-Type Jag. I only managed a beaten up MGB.

This is a really good thriller, written by a retired solicitor. In his younger days, William Kinread was one of 50 prizewinners in a national writing competition. William’s writing was also reviewed by Philip Ziegler who was editor in chief at Collins at the time. He said William ‘had an obvious talent for writing but needed more experience of life’, being only 18 at the time. He qualified as a solicitor, and two years ago stepped down as a partner of a Harrogate law firm to join the family business as a director and legal counsel.

Escapement is his second novel and both books feature the same main character: a young solicitor. Many of the characters, events and locations are inspired by William’s own experiences, and he admits that this adventurous central figure is based on himself.

David Pickup is a partner at Pickup & Scott Solicitors, Aylesbury

No comments yet