To mark its 200th anniversary, Eduardo Reyes looks at the intertwined history of the Law Society and its Chancery Lane headquarters

Richard Atkinson addressed solicitors and ‘distinguished guests’ on Monday 23 June, at the Law Society’s ‘Hall’. As the Society’s current president, he reflected at the bicentenary event on seeing first-hand the ‘diversity and make-up of the profession’ as ‘transformed’ from its foundation 200 years ago. Its membership had soared from 1,200 in the early days to over 200,000.

Monday also saw the publication of the government’s industrial strategy, in which, solicitor general Lucy Rigby KC MP noted, professional services have a central role in enabling and producing growth and prosperity. There are 300,000 legal sector jobs, and law’s trade surplus is £7.6bn.

Only the US has a bigger legal sector. The clear ambition, Rigby said, was for the UK to keep its edge by ensuring it could ‘lead the way in legal tech’.

Less celebrated by successive governments, but part of the Society’s record, has been its willingness to stand up for legal aid, to critique the administration of the justice system, engage in strategic litigation, and oppose policies on immigration and asylum which aimed to override human rights commitments and the courts.

Foundations

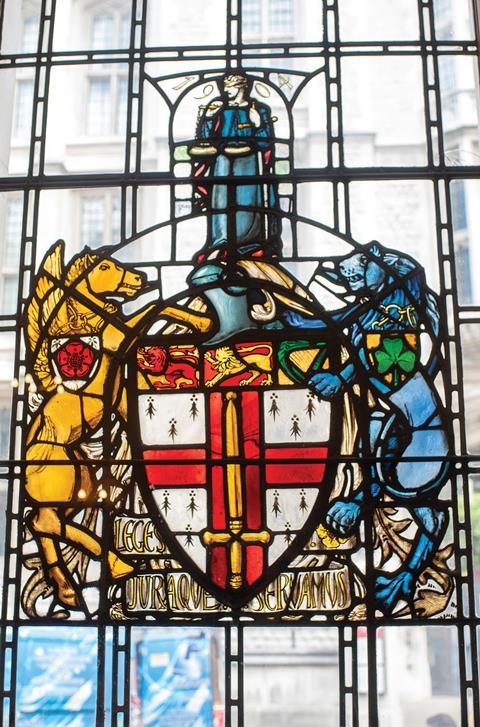

None of the achievements from the Society’s past, now being recounted as part of its celebrations, would have been possible without its Hall, the formal name for its imposing headquarters on Chancery Lane.

By the early 19th century, solicitors and attorneys found their status arguably lower than it had been in the mid-1500s. Until then, the Inns of Court and the Inns of Chancery in London acted as associations and schools for would-be barristers and attorneys. The Inns of Chancery exercised some educational and disciplinary functions over the profession.

Over time, barristers had moved to restrict the benefits of association with the Inns to their own number. In doing so, they achieved an elite reputation, controlling standards, education and legal functions. By contrast, solicitors and attorneys found themselves subject to controls, yet were members of a profession that had a disparate set of associations.

In 1729, parliament responded to public criticism of non-barristers by passing an act ‘for the Better Regulation of Attorneys and Solicitors’. It stipulated that those who wished to practise had to be examined by a judge who must ensure that the man [of course] was of good character and had served a five-year apprenticeship with an enrolled lawyer.

Solicitors were forming associations and societies that aimed at gaining greater professional advantage and a voice on matters that affected them. Autonomous local law societies sprung up from the 1770s onwards – in Bristol (1770), Yorkshire (1786), Somerset (1796), Sunderland (1800), Leeds (1805), Devon and Exeter (1808), Manchester (1809), Plymouth (1815), Gloucester (1817), and Birmingham, Hull and Kent (1818).

In London, legal society the Gentlemen Practisers (founded 1739) scored a notable win. It secured from prime minister William Pitt a ‘conveyancing monopoly’ for lawyers with practising certificates and who had paid the tax government had placed on the PCs. (Each conveyance was also taxed.)

But if more prestige and professional standing were to be attained, something more was needed. And by the late 18th century, there were abundant examples of what that something was. The period saw a flowering of imposing learned institutions and gentlemen’s clubs.

In 1795 and 1796, Joseph Day, a London attorney, advocated the creation of an incorporated society open to all practitioners. The Society, in his proposal, would take the primary responsibility for admission to and the conduct of the profession and would enjoy a proper headquarters, a ‘good Hall near the Temple’.

His idea was revived a few years later by members of the Verulam Club – some of whom were also Gentlemen Practisers. They envisaged a ‘Large Room or Hall in the nature of an Exchange’ on the ground floor provided with newspapers and notices of parliamentary and court business, similar to Lloyd’s Coffee House. Next in importance were a library, clubhouse, meeting rooms, and an office where property and other financial transactions could be registered and clerks recruited. Clerks would use an anteroom while attending their employers.

Bryan Holme, one of the key founding members, embarked on a ‘laborious and careful examination of institutions’ to inform their choices.

The basement would have fireproof rooms for rent. Lectures were later added to the brief. The cost estimate was £25,000 – money raised by the sale of 1,000 shares at £25 each to ‘Attorneys and Solicitors in the Metropolis’. By 1825, the estimate had been raised to £50,000 and London dropped from the title, reflecting national ambitions.

An open competition attracted 62 entries. The winner was Lewis Vulliamy, who had been a prizewinning student at the Royal Academy, and who was all of four years old when Joseph Day first set out his vision of the Hall.

If his final work, the Greek revival ‘option’, with its Ionic columns supporting a pediment, brings to mind a small British Museum, it may be the influence of the museum’s architect Robert Smirke. Vulliamy was his pupil, and the two buildings overlapped in construction.

The original Hall was opened to members on 31 May 1831. Then only as wide as the six-column porch, it was extended according to plans Vulliamy drew up to the north (completed 1850) and the south (1870, with Philip Hardwicke working to Vulliamy’s design as part of other extensions). Pevsner judged the whole effect ‘cool and correct’.

Hardwicke had the most difficult brief of the Hall’s architects. The premises were expanded because of an increase in members and the public duties of examination and registration. To him fell the task of respecting Vulliamy’s original scheme; rearranging the club (previously in a repurposed house) along a north-south axis, and including an exam hall. His work was completed in 1870 and has been the least respected by subsequent alterations – mezzanine floors were inserted in his ‘lofty’ halls.

The judiciary also objected to his design, as the façade did not run neatly parallel to the planned Royal Courts of Justice. It is perhaps a sign of how far the solicitor profession had come since the days of requiring an ‘exam’ by a judge to practise, that the Society disregarded this criticism.

The final extension (1901-1904) was the work of Charles Holden. He brought to it the ‘total design’ belief of an arts and crafts architect. Holden was not ‘limited by the tenets of any particular style’.

His building is ‘free Edwardian’ and ‘mannerist’ and was hugely influential. It experimented with massed blocks and angular surface patterns. The corners and the entire second floor are set back. Its angled and dropped keystones were copied throughout the Edwardian West End.

On details, he collaborated with sculptor Charles Pibworth, who carved four female figures representing Truth, Justice, Liberty and Mercy. They strike a noble attitude but are all bare-breasted. ‘Why, everyone is asking,’ the Solicitors Journal remarked, ‘should the figures be so remarkably destitute of clothing?’

Inside, this is more obviously an arts and crafts building. The wide low entrance to the main staircase adds drama, its lamps have ‘natural’ forms, while ceramic tiles nearby depict trees and foliage. The large Common Room is topped by a large ceramic frieze, dark panelled, and with arched and shelved side areas, built to accommodate books from the now overflowing library.

It is the imposing setting for many admissions ceremonies, its only misstep the striped green marble pillars, a vulgar imposition on Holden by the client.

The Holden extension completed the Hall in its present form. Filled with yellow flowers, it was opened on 23 March 1904 by King Edward VII, accompanied by Queen Alexandra and princess Victoria.

Enter the women

Present at the opening of the Holden extension was London solicitor Edward Bell, as he recalled in memoirs covering the 1890s to 1938. He paints a vivid picture of the centrality of the Hall to the life of solicitors in Edwardian London – a place of professional and social encounters, dinners and transactions.

As Bell watched in 1904, the Hall’s only women were either made of stone and topless, or wafting around its friezes above the Library and Common Room. He would be pulled into the orbit of suffragette London when called upon to witness a will.

‘Mrs Pankhurst I met at the home of one of her supporters who left her whole fortune to a war baby mothered by Mrs Pankhurst. I was present when the Will was signed.’

Emmeline Pankhurst made a strong impression on Bell, who recalled: ‘She had a beautiful voice, which animated an almost fanatical enthusiasm, controlled by a stateswoman’s mind.’

Her daughter Christabel, Bell wrote, ‘possessed a visionary disposition’. Sylvia, he thought, ‘is a wonderful leader and a clear voluminous writer’ whose ‘vivid intensity, can influence a large audience even to political aggression’.

As a direct result of these encounters, Bell used what opportunities he had to promote the admittance of women to the legal profession. Probably around 1910, he took up the issue with the Law Society Council.

Bell then appeared as a witness in Gwyneth Bebb’s (pictured, below) case against the Law Society, the 1913-14 trials which sought to force the profession to admit women. Bell had been called to attest that if Bebb won her case he would offer her articles.

As with suffrage, the first world war tipped the Society in favour of admitting women. On 28 March 1919, the Law Society Council responded to the certainty of legislation requiring the bar to be lifted on women entering the legal professions with a Special Meeting to consider a motion that ended the Society’s previous opposition.

Few spoke against the motion and the vote – 50 in favour and 33 against – was a convincing victory. Council member Samuel Garrett, a London solicitor, former Law Society president and brother of suffragist leader Millicent Garrett Fawcett, caught the mood of the winning side: ‘Minorities,’ he said, ‘had a way of becoming majorities in these progressive times.’

Entry to the profession, though, did not mean its spaces and societies were immediately opened up to women. Until the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, spaces were opened and facilities were provided piecemeal – one space at a time.

At the Law Society’s building, the toilets were a case in point. Women could ask to use a lavatory in the president’s suite of offices on the third floor. There were no dedicated women’s lavatories, despite the urgings from 1919 of the student committee as the number of women students grew.

By December 1922, the solicitor Percy Chambers, father of law student Katharine Chambers, decided enough was enough. He organised the requisite number of supporters to call a Special General Meeting to consider a motion on the ‘imperative’ of providing women with their own ‘lavatory accommodation’. In the same month, Carrie Morrison was admitted as the first woman solicitor. Three more joined the roll in January.

The Society’s officers, the evidence seems to show, hastily commissioned an architect to draw up designs, so that on 26 January the president could face the meeting with the assurance that not one, but four women’s water closets were now planned for members and students, each with a ‘retiring room’ attached.

This was not the end of the contest over space in the Hall. By the 1960s, a growing number of women solicitors and female guests were running up against arcane etiquette relating to Chancery Lane’s dining and social facilities. A woman solicitor could bring a male guest to lunch, but not a non-lawyer woman guest; neither could a male lawyer bring a non-lawyer woman guest. The solution reached by the Council was not to change the rules but to create the Ladies’ Annexe, where male or female solicitors could bring their women guests to drink and dine. It was opened in 1961 by actor Sid James (pictured, below), and closed its doors in 1975, when dining and social rules were equalised.

On the Council, there was a long wait for the first woman member. Two years after the closure of the Ladies’ Annex, Eirian Evans was elected and served five years. She brought, the Gazette reported when she stood down in 1982, ‘good common sense, and to those of the Professional and Public Relations committee, a feminine viewpoint which was particularly useful in the work of the subcommittee on Sexual and Racial Discrimination’.

In time, improving the legal profession’s record on equality and diversity in its membership would become a significant focus. In his inaugural address Mark Sheldon, president in 1992, stated his support for ‘firm but tempered measures’ to tackle the discrimination women lawyers still faced in their professional lives.

In 2002, the Society chose its first woman president, Carolyn Kirby. Fiona Woolf, a future lord mayor of London, followed in 2006. In total the Society has had seven women presidents, including I. Stephanie Boyce (2021), the first Black president, and Lubna Shuja (2022), its first president of south-Asian descent and first Muslim. The next deputy vice president, Dana Denis-Smith, is founder of the First 100 Years project, a digital resource preserving a record of women in the legal profession.

In 2019, marking 100 years of women in the law, president Christina Blacklaws launched the Society’s ‘Women in the Law’ pledge which, with more than half the profession now women, aims at improving their representation in positions of leadership. ‘It’s deplorable there aren’t more top women in law,’ she noted.

The 2007 Legal Services Act, which aimed at liberalisation of the ‘market’, also enshrined the goal of supporting and improving equality and diversity, expressed in the Solicitors Regulation Authority’s Principle 7: ‘You act… in a way that encourages equality, diversity and inclusion.’

Groups like the Black Solicitors Network had long raised issues of under-representation and discrimination in the profession, and provided career support to members, aims now also reflected in the work of the Society’s Ethnic Solicitors Network. There are also networks for women solicitors, disabled solicitors and LGBTQ+ solicitors.

Day in court: strategic litigation

The Law Society periodically has recourse to the courts through strategic litigation. In January 2024, the Society sought judicial review of the Ministry of Justice’s decision to ignore recommendations for a minimum 15% uplift of legal aid rates contained in the Independent Review of Criminal Legal Aid.

The MoJ had decided solicitors should receive a 9% increase to criminal legal aid funding in 2022, with a promise of a further 2% by 2024 – a real-terms cut to rates.

The Society’s case highlighted the MoJ’s decision-making process and why it ignored the minimum recommendations.

The High Court ruled in the Society’s favour on the grounds that:

- the government’s decision was irrational;

- the lord chancellor did not make proper enquiries before making his decision.

Changing role

The role of the Society has changed significantly since its foundation. Through much of the 19th century, a good part of its power and influence lay in reviewing legislation for successive governments, a role that faded as ‘officialdom’ increased in Whitehall. Alas, the days when presidents were routinely knighted are long gone. Its legislative contribution now occurs through submissions to government consultations, and public commentary on the operation of the law.

However, the Law Society has at times had a direct role in ensuring access to justice. From 1973-1988 it administered the legal aid ‘Green Form’ scheme, which made advice and assistance available in matters concerning English law on the basis of a quick means test. It worked directly on the duty solicitor scheme established for advice in police stations, established in 1984.

Chancery Lane campaigns on topics such as legal aid, the condition of the justice system, and concern for the status and safety of lawyers and judges when targeted or criticised. It also engages in strategic litigation (see box).

With its disciplinary function passed to the SRA, Chancery Lane’s focus is now on representation and services to support solicitors, and to serve the public interest on justice.

Numbers, Richard Atkinson was able to note, have increased around the world – there have been bicentenary celebrations ‘from Cardiff and Newcastle to Singapore and Dubai’.

The place of the building has also changed. As the Society shed its role in education and qualification, conferences have replaced lectures. There is just one restaurant, not four.

But without the Hall, there would be no Law Society of England and Wales; its role and status underlined as new entrants pose for photos before its columns on admissions days. And each year, it is the symbolic start and finish point for thousands of participants in the London Legal Walk, the largest gathering of lawyers anywhere in the world, completed in support of law centres and legal charities that provide access to justice for people who would not otherwise have it. Here’s to the next two centuries.

No comments yet