It may be that we are witnessing a high point of interest in women’s legal history. Animated by the upcoming centenary of women’s formal admission into the legal profession, projects like the Women’s Legal Landmarks project, First 100 Years and this publication’s ‘women in the law’ pages have captured the imagination and zeitgeist. Never before have the names, struggles and successes of the early – and not so early – women lawyers been so familiar. And quite right too. A huge amount of information has now been placed in the public domain and we are all beneficiaries of it.

As with fairytales, these stories can bewitch the reader – offering a moment of escape, of detachment or freedom, fostering feelings of inclusion, communication or belonging. When we listen to stories we not only begin to understand their world differently, but ours too. And yet, to stay with the story of a fairytale is to misunderstand their purpose. It is not the story of a fairytale itself that is important, but rather where that story takes us. So too the stories of women in law.

Told well, the stories of women’s engagement with and in the law are a call to arms to anyone who cares about the position of women in law, and society generally. The telling and collating of these stories is a political – a feminist – act. Part-historical record, part-guidebook, we collate and tell each other these stories not simply in the pursuit of accuracy and completeness (though that is important). Rather, we acknowledge and celebrate the lives, efforts and achievements of individual women and women’s organisations and groups, as a means of challenging the injustices of the present and setting the agenda for the future.

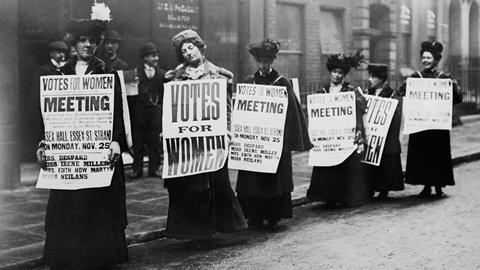

Of course, women’s proactive engagement with law did not begin in 1919. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that women acted as ‘lawyers’ well before their formal admission. Women have engaged with law from medieval times, for example as landowners, as litigants bringing actions in law and equity, as Poor Law guardians or school governors, and as authors of legal texts. There are also many examples of women and women’s groups engaging with law and law reform. Often the campaigns have focused on specific issues: equal pay, reproductive freedom, access to property, political representation and so on. Some of these are now familiar – the Married Women’s Property Acts, for example. Others less so. Consider, for example, the role that women played in campaigns for the abolition of slavery, the creation of international law, the development of trade unions, or against cruelty to animals and birds. Women – lawyers or otherwise – have been at the forefront of legal reform and campaigns for well over 200 years.

From the stories of women’s legal history, of the women and men who made (and sometimes failed to make) history, we learn that law reform is messy; sometimes conflicted; never simple; unpredictable; usually time – and personality – dependent; and often flawed. We learn of the need for, and effectiveness of, a multi-pronged campaign, combining legislative reform, court cases or piggy-backing on an unrelated measure or issue. We learn that the legislation or decision that results is, more often than not, the product of compromise: a (hopefully temporary) foothold from which to secure further reform. It was, for example, a full decade after the enactment of the Representation of the People Act 1918 before many of the women who campaigned for the vote were actually able to exercise it. It took two-thirds of a century to get rid of the double standard, put on a statutory footing in the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857, which allowed a husband to divorce his wife for adultery while requiring that a husband’s adultery be compounded by another matrimonial offence.

We learn that while ‘exceptional’ women stand out, they rarely stand alone. Instead they are surrounded and supported by (feminist) networks, professional organisations or campaigns, or leading public figures.

While law reform alone cannot secure real change in women’s lives (it is not a panacea for all forms of disadvantage, violence and discrimination faced by women), it has been, and can be, a tool to advance their cause.

In an age of #MeToo, when women are being pursued in the courts for speaking out about sexual violence, when new mothers are still in need of protection against discrimination in the workplace, when women continue to be underrepresented in public life, it is important to acknowledge, respect and celebrate the many women and feminists who – standing alongside and on the shoulders of each other – used law as a mechanism for change and justice.

Erika Rackley is a professor of law at the University of Kent. Rosemary Auchmuty is a professor of law at the University of Reading. Together they led the Women’s Legal Landmarks project

1 Reader's comment