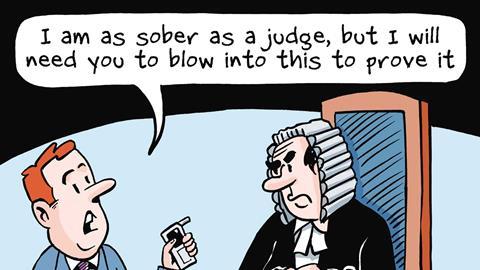

Peter Glover considers how breath-test devices can help facilitate ‘contact’ in family cases.

Private Children Act cases in the family court are bedevilled by numerous complications, such as allegations of domestic violence and/or alcohol and drug abuse, for which there are no easy fixes. However, the object of this article is to demonstrate how one of them, actual or alleged abuse of alcohol, can be managed, and in some cases resolved to the satisfaction of both parties and the court.

All judges and practitioners in this field will be familiar with the objection to (what I will for the sake of simplicity refer to as) ‘contact’ on the ground that the parent seeking contact is a drinker. While it is not the law that a parent who drinks cannot see his/her child, it is probably the law that a parent unable to care adequately for his child by reason of intoxication should not be entrusted with such care.

This article and the directions which follow proceed on the basis that the father is said to be the drinker, but my personal experience over 19 years in the county court is that it is almost as likely to be the mother.

In the context of drug abuse, hair -strand testing is reliable evidence that a parent either is or is not consuming illicit drugs, but in the context of alcohol abuse, these tests do not reveal the amount of alcohol consumed. While liver function tests may do so, unless the liver is permanently damaged by alcohol, they provide only a ‘snapshot’ of recent consumption, if any.

Often, in response to the allegation, the father will say that he does not drink when with the child. If Cafcass is asked to report on contact at this stage, the court will frequently be told that the safety of the child cannot be guaranteed unless the father stops drinking. We are not told how this might be achieved, and in the meantime there is the prospect of an indefinite suspension of contact or delay in putting contact in place.

About five years ago, I became aware of the existence of cheap, portable, multi-use breath-test devices, available in the high street, or online, which are intended to allow drivers who have had ‘one (or more) for the road’ to check whether they may legally drive. It seemed to me that the use of such a device before and after visiting contact would allow the father to prove his sobriety on collection and return of the child. The device would also allow the father, returning the child on Sunday after staying contact, to demonstrate (subject, of course, to his metabolism and the rate at which his body removes alcohol from the bloodstream) on the balance of probability that he has not been drinking heavily while the child has been in his care.

I have directed the use of these devices in almost every case I have had since then, where allegations of alcohol abuse have prevented the commencement of contact, or left it stuck in contact centres, and in virtually every case so far, use of the device has allowed contact to progress. Best of all, in many of these cases, the use of the device for six, nine, 12 months has resulted in the mother accepting that the father really does not drink when the child is with him. This development of trust in so sensitive an area often spreads beyond the immediate context and has resolved a significant number of previously ‘intractable’ contact cases.

There are already a number of judges at all levels making use of these cheap and reliable devices, and I hear from time to time of their success outside north-west Kent.

Some of these devices store sample data, while others provide a print-out. The cheapest indicate the outcome on a dial, or by illumination.

An ideal time for use is six months, but where the other parent is very wary, or the provision of samples mitigates other issues, use can be indefinite. Where drug use is also alleged, control of the alcohol in this manner will, in my experience, often encourage a reluctant mother to allow contact, and even where hair-strand testing is beyond the parents’ means.

An online search earlier this year (search Amazon for alcohol breath testers) found adequate devices for about £30 to £100.

However, if you have neither heard of nor used a breath-test device in an appropriate case, I have set out below a draft direction which you might propose to the court or the parties. I should be very interested to learn of your experiences.

Standard breath-test direction

- The father shall before the first contact date for which this order provides purchase a breath-testing device and a supply of tubes/straws, which he shall hand to the mother immediately before that first contact, together with a notebook in which the breath-test readings can be recorded.

- It shall be the duty of the mother to keep the device and the notebook safe and available for inspection by the judge as and when required – and in default of her so doing, the court may draw adverse inferences in the event that she subsequently fails to comply with the contact order herein by reason of the father’s alleged use of alcohol.

- Immediately before the first contact and at the end of that contact, and at the beginning and ending of all subsequent contacts, the father shall provide a specimen of breath, and the reading shall be recorded in the notebook and initialled by both father and mother.

- The parents shall ensure that so far as is possible the breath sample shall be given in private and in any event not in the presence or vision of the child[ren].

- In the event that the sample tested before contact discloses the presence of alcohol, the contact shall not take place. In the event that the sample tested after contact discloses the presence of alcohol, the next contact shall not take place. In either event, the mother shall as soon as is possible thereafter apply to [name of judge with conduct] without notice to the father with a witness statement, stating the outcome of the relevant breath test and exhibiting any corroborating documentation for an order that the contact ordered herein shall be suspended until further order.

- For the avoidance of doubt, the mother is reminded that the use of the breath-testing device is a temporary measure until either she accepts that the father does not drink during contact visits, or the judge reaches that same conclusion, and whether she is in agreement or not.

District Judge Peter Glover sits at Dartford County Court

No comments yet