Lawyers and other compliance managers are being stretched as government agencies outsource responsibility for policing corporate impropriety. Eduardo Reyes reports.

Former employees of one state regulator that went through a ‘bad patch’ had a catchphrase for senior managers’ reaction to any mishap. ‘Find me six people to blame,’ they would quip. The line neatly conveys the common human instinct to push responsibility on to other people – to get out from under whatever is bearing down on them.

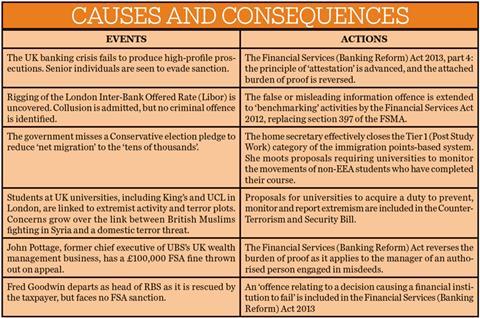

Perhaps, then, it is no surprise that policy-makers and regulators who have been at the centre of controversial failures – think banking regulation, immigration, fraud and failure to identify homegrown terrorism – have been seeking to spread responsibility for ‘policing’ the system.

The charge that we face a ‘rising tide’ of legal and regulatory ‘burdens’ is hardly new – law firms have published research aimed at press and clients that confirm the argument going back a decade or more.

What is new is the way that responsibility for compliance is being, by turns, personalised and delegated. As Alex Ktorides, a partner at Gordon Dadds Consulting, argues: ‘We are witnessing a “pass-the-parcel to business” approach to policing improper or illegal behaviour in the corporate world from the regulators and crime agencies, such as the FCA, SRA, SFO and the OFT.’

Recently, the public sector, and universities in particular, have been subjected to the same approach, with responsibilities to deliver immigration monitoring and enforcement, and proposed duties to prevent extremism and track the movement of former students from outside the European Economic Area.

Self-regulation

The lineage of this trend is the principle of ‘self-regulation in the regulated industries’, Ktorides notes, starting in the early 2000s. However, the outcomes-focused principles that guided the operation of bodies such as the Financial Services Authority, as set out in the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, were also shaped by the controversial ‘light- touch’ ethos then in vogue.

One starkly perceptible shift came with the response of policy-makers to the banking crisis, exemplified by the replacement of the FSA with the Financial Conduct Authority. The Financial Services (Banking Reform) Act 2013 introduced what WilmerHale’s white-collar crime specialist Elly Proudlock notes is the ‘personal responsibility’ that the previous regime lacked.

‘Statements of responsibility’ – where ‘specific individuals are asked to sign off on what they are responsible for’ – are outlined in part 4 of the 2013 act and are, Proudlock says, ‘the big one’. ‘Individuals are being asked to attest to quite a lot more,’ she adds.

Driven by ‘scandal upon scandal, and a public desire to see people held to account’, the responsibility accepted by an individual through statements of responsibility is significant. ‘The most draconian change is an effective reversal of the burden of proof,’ Proudlock explains. ‘If you as a senior manager were responsible for an [errant] authorised person, then you are guilty of misconduct. It can be rebutted, but the burden of proof is on the individual.’

Such principles will be extended by the Serious Crime Bill. A wide-ranging piece of legislation, this encompasses emotional distress caused to children, economic crime, female genital mutilation and terrorism. Of particular interest, Ktorides says, are proposals to introduce new offences for failing to identify and put a stop to economic crime: ‘The regulated sector is already labouring with risk assessments and effective compliance strategy and this will only increase the demands on both regulated and non-regulated [entities].’

It can be argued that such ‘burdens on business’ are reasonable given the traumas of the past few years. The banking crisis, mis-selling of interest rate swaps, Libor-rigging (the list goes on) have produced little in the way of tough personal sanction, with culpability involving deceit or ineptitude seemingly close to impossible to establish.

Certainly some changes look less like a burden on commerce, and more like retrospective censure for those responsible for past misdeeds. For example, the ‘offence relating to a decision causing a financial institution to fail’, included in the 2013 act, seemed to be drafted with former RBS boss Fred Goodwin in mind. It ruffled a few feathers in the financial services sector, but in reality banks have risk management procedures that defendants can likely cite in their defence.

While the removal of the ‘dishonesty’ test for criminal cartel offences is not a substantial change, the failed prosecution of individuals in the 2010 British Airways alleged price-fixing affair that seemed to prompt this change was caused by wider failings in the prosecution case.

Proudlock notes that even the more substantive responsibility of managers for the actions of authorised persons seems to be ‘designed backwards’ – from the FSA’s inability to make a £100,000 fine stick against John Pottage, former chief executive of UBS’s UK wealth management business. The fine, for failing to implement proper checks on the desk he ran between 2006 and 2007, was reversed on appeal to the Upper Tribunal for Financial Services.

*Correction: the right-hand column on the second row following ‘part 4:’ should read: statements of responsibility are introduced, and the attached burden of proof is reversed.

The emphasis on compliance and individual responsibility has certainly hiked compliance costs. Ktorides notes: ‘Directors and officers carry an increasing burden relating to corporate fraud, the regulated professional and business-facing additional offences, such as professional enablement of money laundering. This means spending money on compliance planning, risk assessment, and effective monitoring and reporting systems.’

With statements of responsibility, Proudlock notes, one consequence is certainly an increase in legal costs: ‘It creates the need for really good, experienced lawyers – to advise not just when you might face an enforcement action, but at the point when you are signing off. It’s clearly paramount to have everything tightly drafted. There’s a lot more of that.’

In one context, namely immigration policy, a greatly increased compliance burden – attended by enhanced liabilities – has been in place for businesses and further education institutions for some time.

Nichola Carter, principal at niche immigration firm Carter Thomas, says: ‘The points-based system [for immigration] has basically given the word “risk” an entirely new meaning.’

Education providers and businesses obtaining a sponsor licence are told that they must ‘play their part in helping to prevent the system from being abused’. She adds: ‘In reality, however, those very same entities find themselves labelled as the abusers for failing to comply with a system that is simply impossible to comply with.’

Different caseworkers apply different interpretations to what are, at best, ‘unclear sets of guidance for sponsors to follow’, Carter adds: ‘Frequent policy changes have been criticised heavily by the judiciary and the correct procedure for laying immigration rules has been almost wholly ignored for years.’

The organisations affected and their advisers try to manage ‘not only the known risk of a minor oversight triggering a licence revocation, but the unknown risk of this government changing entire swathes of policy without any regard for the impact on business, for no other reason than to be seen to be trying to reduce net migration’. It is, she insists, a goal which is ‘unachievable in the current economic climate and while those coming and going from the EU continue to be counted’ (see also Legal Update).

Immigration lawyer Katrina Cooper, counsel at Faegre Baker Daniels, confirms the direction of travel: ‘The current tracking and compliance obligation is for non-EEA migrants. However, the intended legislation would throw the net over all students – that’s a mammoth task for any university.’ She adds: ‘There is no current legislation that similarly impacts employers, but if there were I would have serious reservations that it would be administered proactively by many. Some still struggle to comply with simple right-to-work checks.’

Another looming headache for higher education institutions is the proposal in the Counter-Terrorism and Security Bill for a legal duty to prevent extremism. It is a point that May has been pressing since 2011, when she urged universities to get their house in order. A Home Office consultation paper issued just before Christmas said universities should ‘take seriously their responsibility to exclude those promoting extremist views that support or are conducive to terrorism’.

As currently configured, staff would be expected to refer students at risk of being drawn into terrorism to external anti-radicalisation programmes; and to challenge extremist ideas, including non-violent extremism, that can be used to justify terrorism. Privately, university in-house counsel tell the Gazette they remain hopeful of key concessions regarding section 5 of the bill.

If you as a senior manager were responsible for an [errant] authorised person, then you are guilty of misconduct. It can be rebutted, but the burden of proof is on the individual

Elly Proudlock, WilmerHale

‘We live in difficult times,’ Kingsley Napley’s Michael Caplan QC, a critic of the proposed legislation, concedes. ‘Many believe there should be some restriction on extremist speeches, for example in places of education.’

The issue of whether speakers should be ‘no-platformed’ is already being played out. Goldsmiths, University of London, hit the headlines recently over its comedy society’s decision to cancel a comedian’s appearance because the themes of her show had led to threats of protest. The society cited complaints from students about comic Kate Smurthwaite’s ‘position on sex work, religion and Trans issues’, and the ‘possibility of a picket line’. Ironically, her show was to focus on the subject of free speech.

Deciding precisely what constitutes ‘extremism’ is difficult enough in itself, Caplan points out. ‘The definition of extremism has caused a row between ministers, and I anticipate preparing the guidance itself will not be easy,’ he adds. Given what is proposed, Caplan says he ‘can just begin to see the problems that will arise if the government uses the power of a court order to enforce it’.

The gradual shift, then, to a more onerous – and hazardous – climate of self-regulation is problematic for all concerned. Solicitors will be familiar with the growing costs of conducting due diligence on clients, especially where they are deemed to be ‘politically exposed persons’ (see Gazette roundtable).

In addition to the compliance burden, lawyers advising clients on their enhanced duties point to the problems faced by regulators themselves. Hamstrung by tight budgets and grappling with the same uncertainties faced by those they ‘police’, regulators of all stripes still need to intervene and enforce.

Referencing statements of responsibility, Proudlock notes: ‘It relies on the deterrent effect.’ At the point of signing off, the size of the individual responsibility expressed should give the senior manager pause for thought – prompting the right questions, or putting front of mind any doubts they might have.

But there is surely an over-reliance on such a deterrent. Proudlock questions if the resources for full enforcement against ‘responsible’ individuals will ever be available: ‘In context of a major event, authorities could divert all their resources into one action – it’s a lot to bite off.’

Enforcement action where authorities lack resources can also be arbitrary. Immigration is a case in point, says Carter: ‘Under the current government, bona fide education providers and businesses alike have been subjected to heavy-handed treatment by UK visa and immigration officials for, in many cases, nothing more than forgetting to file a document on a specific file.’

There is no suggestion that policy-makers believe they have hit upon a principle to be systematically rolled out in all areas of regulation, compliance and law. But in area after area, the response to policy-makers and regulators’ embarrassment, shock or frustration when faced with an unwelcome outcome has been to fall back on policies based on enhanced individual responsibility, self-regulation, invasive powers and tools such as statements of responsibility.

If universities are successful in resisting a duty to prevent extremism, it will be a rare victory. In most other areas of policy, the ‘official’ direction of travel has been one way.

Eduardo Reyes is Gazette features editor

No comments yet