It will not come as a surprise to anyone that, as a former solicitor and now courts minister, I am immensely proud of the UK’s court system. Our legal services are the best in the world and it is no wonder to me that their reputation stretches around the globe. I am proud, just like others in the profession, of the achievements that have followed the regular long hours of hard work we have put in.

But our civil courts, where much of our legal business takes place and where most of this glowing reputation has been forged, rarely get to spend time in the limelight.

The media prefers to focus on the drama of the criminal courts, and eagerly debates every high-profile case and sentence, especially when a celebrity is involved.

Which is perhaps why there has not been much interest in the quiet revolution that is happening in our civil court system; changes which I believe will help us to sustain and build on our outstanding global image.

On 22 April the new single county court for England and Wales will become operational, bringing with it a series of commonsense changes which will complete several years of work and make the civil courts more modern, efficient and, most importantly, better for all users.

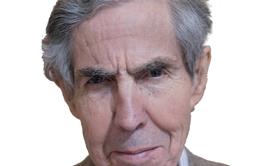

These changes represent the end result of recommendations first made by the retired lord justice of appeal Sir Henry Brooke, who was commissioned to carry out a review in 2008, and which were taken forward by the government as proposals in the 2011 Solving Disputes in the County Courts consultation.

For Gazette readers, as regular users of the courts, it is important to be aware of the changes coming into effect, which will mean differences in the day-to-day business of the courts.

The biggest change will be the establishment of the single county court itself. The title could perhaps be confusing to the uninitiated, so let me make clear what it does and does not mean. It does not mean there will be one single physical building where all civil cases will be heard. We will continue to have county court hearing centres across the country which will correspond to the existing locations.

What it does mean, however, is that jurisdictional barriers will be removed, which in the past have prevented some cases from being issued at, or moved to, the most suitable venues and, more importantly, prevented the best and most efficient use of judges’ time, as well as the other resources needed to hear cases at different levels. It will also allow us to make improvements behind the scenes so our courts can run more efficiently and flexibly.

For users, the most notable effect of all the changes will be that they can submit claims more easily and they will find that the whole system runs more smoothly.

Removing bureaucracy

Alongside the creation of the single county court, we have abolished the need for the lord chancellor to give his approval for every occasion that a High Court judge hears a case at a county court, removing an unnecessary layer of bureaucracy and making sure judges can sit where they are needed.

We have also made a series of changes to the powers that can be exercised by the different levels of the civil court system.

We all know that house prices in the UK have soared over the past two decades. But the maximum limit for the value of equity cases which can be held at local county courts had, until now, remained unchanged since the 1990s at £30,000. Any cases above that level had to go to the High Court, creating an ever-greater workload burden. So we have raised that limit to £350,000 to reflect current house prices so that these cases can once again be settled at local county courts without the delay of going to the High Court.

Similarly, for cases about claims for money, we have increased the minimum value where cases can be commenced at the High Court, from £25,000 to £100,000. This again reflects long-term inflation and will make sure county courts can deal with smaller cases more quickly and the High Court will not be unnecessarily clogged up. The exception to this will be for personal injury cases, for which other reforms have already been put in place over the past few years, including the overhaul of ‘no win, no fee’ deals, and the creation and extension of the claims portal, which now sees tens of thousands of cases dealt with quickly and efficiently.

In the 22 April changes, we have also made it possible for freezing orders to be issued in more circumstances at the county court, to reflect the higher value of the cases they will be hearing.

Reducing the caseload burdens from the High Court has also enabled us to make changes so its expertise can be used to hear some specialist proceedings, including applications to vary trusts and reduction in capital cases, which will no longer be heard at county courts.

Bailiff reforms

Of course it is not just the single county court which will come into effect next month. On 6 April the enforcement process will be overhauled too, when our substantial bailiff reforms are implemented, signalling the end of bad behaviour from enforcement agents, with new conduct rules, a formal fee structure and a certification regime to ensure bailiffs are properly trained.

All of this means that our civil courts will work quicker and better for those who look to them to resolve disputes, which has got to be good news.

These changes are the result of a lot of work over several years from many in the judiciary, legal profession and elsewhere and I would like to express my gratitude to them. They may not have attracted the attention drawn to dramatic criminal cases, or even other reforms made by the Ministry of Justice, but they will make a notable and positive change to our courts and allow us to continue building on the formidable reputation of our legal services.

Shailesh Vara MP is justice minister responsible for the courts and legal aid

Topics

Justice stalwart Sir Henry Brooke dies at 81

Tributes are pouring in from the profession after the retired judge passed away following heart surgery.

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Courts reform

- 7

- 8

No comments yet