THE LOW DOWN

By the early 1980s, following a string of miscarriages of justice, faith in the ability of the police properly to conduct searches, gather evidence and interrogate suspects had collapsed. The establishment’s response was the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, which sought to assuage concerns about officers cutting corners and ‘fitting up’ suspects. PACE was a seismic development in the wake of an era when officers routinely withheld suspects from solicitors and ‘edited’ confessions. Yet successive home secretaries, keen to be seen to be tough on crime, have challenged the legislation’s founding principles. So how well has PACE aged? And can the ethos it embodies survive both the digital revolution and the demographic decline of criminal defenders?

For TV dramatists an easy way to date a detective series is to depict police officers behaving with impunity in their treatment of evidence, witnesses and suspects. For justice to be done, a stand is often seen to be taken by an officer who believes the expedient route to a conviction fell short.

Disquiet about sharp practice by the police coalesced around a growing number of miscarriage of justice campaigns and the Royal Commission on Criminal Procedure. The response to the commission’s recommendations was The Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE). This unified police powers under one code of practice and attempted to balance carefully the rights of the individual with the powers of the police. Specifically, PACE mandated audio recording of all suspect interviews, the right to legal representation for suspects and limits on detention before charge.

Some 36 years on, its provisions and processes have been revised through codes of practice (set by the Home Office). Meanwhile, at certain times legislators have passed one or more criminal law acts a year. The codes governing such areas as the power to search people and properties, and to seize items, have been the focus of controversy and revision.

Yet the then-revolutionary principles underpinning PACE supposedly endure. How well, then, has the act aged? And how well did it achieve its aims?

Immediate effect

Experienced criminal lawyers and those who helped shape policy in this area are clear – the impact of PACE was dramatic and immediate. It protected rights at the same time as radically changing the culture of policing. Before PACE, ‘officers tried all sorts of tricks of the trade, such as losing your client’, recalls veteran criminal law solicitor Anthony Edwards, who retired from East London firm TV Edwards last year. ‘The first achievement of PACE was how to help you find them.’

Andrew Lockley worked on the Law Society’s submissions in the creation of PACE and the duty solicitor scheme on which it partly depends. He currently chairs two independent policing panels in South Yorkshire. ‘The most important issue for solicitors,’ Lockley says, ‘was the lack of legal advice at the police station. There was no statutory right, though sometimes legal advice was made available. Today’s solicitors, trained in PACE, have no idea how different it was over 30 years ago.’

While PACE came as a response to miscarriages of justice, behind this lay wider public concerns about how the police dealt with suspects and the perception of a deeper institutional malaise. The pre-PACE era’s best remembered miscarriage of justice cases, the Birmingham Six and the Guildford Four, related to extraordinary events – but police ‘fit-ups’ were exposed in less politically charged cases.

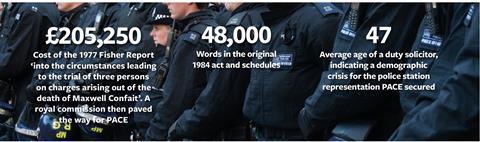

An investigation into the 1972 killing of male prostitute Maxwell Confait saw three youths jailed based on the evidence of their false confessions. Rarely referenced now, the facts of the investigation were picked over in detail in the 1977 Fisher Report, completed by Sir Henry Fisher for the House of Commons. PACE was also shaped by the conclusions of the 1981 Scarman Report, which concluded that policing mistakes were a crucial factor igniting the disorder of that year’s Brixton riots.

Today’s solicitors, trained in PACE, have no idea how different it was over 30 years ago

Andrew Lockley

The police backlash against Scarman, which included controversial press briefings, signalled that resistance to cultural change was ingrained in the force. Did PACE really manage to effect a dramatic change in culture?

The point remains moot. Law professor Michael Zander QC, who was closely involved in the creation of PACE, argues that the shift was instantaneous, something he learned from training officers in police forces across the country. He recalls they were ‘very nervous and worried, understandably’, and says he ‘heard over and over again from old salts how this would change everything’. However, Zander says they ‘got on with the job’.

Edwards Duthie Shamash partner Shaun Murphy is more cautious. The police, he said, ‘didn’t understand how restrictive PACE is in practice’ until Court of Appeal judgments went against them. Crucially, the meaning of ‘unfairness’ was clarified in R v Samuel [1988], R v Walsh (Gerald Frederick) [1990] and R v Keenan [1990]. It was, the court held on each occasion, unfair to introduce evidence that had been obtained in breach of PACE. It was, Murphy says, ‘these cases’ that ‘helped to shape the attitudes of police officers and lawyers’.

Murphy also suggests that in the 1980s judges took a view that the police could do ‘no wrong’ and generally ‘whatever they wanted’. But ‘this has changed’. Crown court willingness to see breaches of PACE in police searches as ‘insufficiently serious’ to be unlawful was corrected on appeal in Osman v Southwark Crown Court [1999].

Revisions

Some revisions to PACE codes have been broadly welcomed. The Policing and Crime Act 2017 revised Code C (detention) to increase safeguards for vulnerable suspects. A change to Code C, effective last year, secures access to menstrual products for women in custody.

Others have been controversial. The Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 broadened police powers of arrest without a warrant. The Terrorism Act 2006 extended pre-charge detention for terrorism suspects to 28 days, amending PACE’s Code H. PACE is also at the centre of the police’s controversial ‘stop-and-search’ powers, a consistent source of tension between the police and inner city BAME communities. In 2009, the requirement for a written record of such searches was watered down. The police need only issue a receipt to the person stopped and make a record of their ethnicity.

Nevertheless, Kingsley Napley associate Matthew Hardcastle says: ‘To a great extent PACE has worked well. It has stood the test of time. It is hard to follow why a succession of home secretaries have seen fit to make calls for an overhaul.’

One area where the delineation of police and state power has been overtaken by developments is the explosion of digital evidence and attendant advances in surveillance capability. Here, the promises of fair treatment contained in PACE can sometimes seem quaint.

Big Brother Watch, in its July 2019 report Digital strip searches: The police’s data investigations of victims, states: ‘It is clear that police’s unrestricted and disproportionate approach to taking vast swathes of victims’ personal information in so-called consensual digital searches goes far beyond the comparable legislative regime regulating consensual physical property searches.’

But is PACE really dated here? ‘A search of a phone is like checking someone’s pockets,’ Murphy points out. ‘The law has not changed in that respect and I’m not sure that it needs to.’ He says ‘PACE has kept up in that sense of the common law approach to searching for any evidence which is relevant’. However, he suggests: ‘People putting everything on their phones has made it easier now for the police to collect evidence. Lives are lived on phones so it is easier to check locations, find pictures. The average citizen doesn’t understand how much they really make it easier for the police. This is not really a PACE issue, it’s an educational issue.’

Lockley says: ‘The bigger issue is the capability of officers to actually sort the wheat from the chaff: the stuff that is important and the stuff that isn’t.’ Hardcastle suggests if a smartphone is searched, the ‘big difference’ is that ‘people don’t necessarily know what’s on their phone, and whether what they deleted has been deleted. They’re not aware what is lurking in the cloud or what spyware there might be. The scope of search for a smartphone is different than for a flat or estate. Probably a structure is needed to be put on that.’

Zander is clear on another point: ‘Strip searches are not satisfactory. The College of Policing is working on changing this, but it is not going far enough.’

Breaking code

PACE Code A: deals with the exercise by police officers of statutory powers to search a person or a vehicle without first making an arrest. It also deals with the need for a police officer to make a record of such a stop or encounter. In 2009, Code A was amended to remove lengthy stop and account recording procedures, requiring police to record only a subject’s ethnicity and to issue them with a receipt.

PACE Code B: covers police powers to search premises, and to seize and retain property found on premises and persons.

PACE Code C: sets out the requirements for the detention, treatment and questioning of people in police custody by police officers.

PACE Code D: concerns the main methods used by the police to identify people in connection with the investigation of offences, and the keeping of accurate and reliable criminal records.

PACE Code E: concerns the tape recording of interviews with suspects in the police station.

PACE Code F: covers the visual recording with sound of interviews with suspects.

PACE Code G: deals with statutory powers of arrest.

PACE Code H: relates to the detention of terrorism suspects. In 2006 their detention without charge was set at up to 28 days.

Youth – evidence, interviews and custody

PACE’s requirements and codes, and the protections they provide around representation and interviews in custody, are not, Edwards argues, working well for minors. The definition of the ‘appropriate adult’ who can accompany a minor in an interview needs close attention, he says.

What exists ‘is better than nothing’, Edwards notes, but he points out that a parent may be the wrong person to fulfil the role. Parents may have chaotic personal lives or have a record of aggression towards their child; and the child could have lied to their parents, a fact that may come out during interview. The minor is a suspect, but might also be a victim. In addition, Edwards points out: ‘Youngsters in these situations find it incredibly difficult to talk to an adult. They may not have experience of being in a police station. They feel threatened there, but they are also worried about the gang culture outside. It takes a lot of skill to talk to them about these pressures.

‘In the modern, well-trained police force, in a world of county lines and gang culture, there is a need to understand that the suspect may also be a victim, and they need a solicitor there to help them.’ Yet current pressures undermine the positive role a solicitor should be able to play. ‘Our difficulty is that it takes time to establish our credentials [with them as clients], and we need to spend time with them.’

PACE has stood the test of time. It is hard to follow why a succession of home secretaries have seen fit to make calls for an overhaul

Matthew Hardcastle, Kingsley Napley

Hardcastle says: ‘There has been an impression for some time now in the criminal justice system that children need different treatment.’ At present, he says: ‘As soon as you put them into police custody they will perceive themselves in a particular way.’

A much older group of people presents a problem for the continuing operation of PACE – solicitors.

Arguably, the real threat to legal representation, a cornerstone of PACE, is not a home secretary hell-bent on a tough approach to crime, but the increasing age and falling number of criminal law solicitors willing to take the duty solicitor role.

The Law Society recently published new data which maps out a looming crisis. Lockley explains: ‘A significant change with PACE was the offering of the duty solicitor scheme. Not only did suspects get legal advice, they knew they had rights and they knew they would get a duty solicitor or representation.’ Lockley says the shortage of people coming into the profession is ‘directly applicable to rates of pay’.

Edwards agrees: ‘There is going to be a problem over the next 10 years. Not today, but it is coming.’ Zander says there is ‘a problem of getting young people’ in to criminal law practice, ‘and it is a very serious one’.

The average age of a duty solicitor, Hardcastle notes, is 47: ‘There is a vast gap that will open as they end their career, and there is no quick way to fill the gap between the young now and the duty solicitors looking to retirement. There is no succession plan.’

It is difficult to see how the government can avoid finding a policy response to this demographic time bomb. Prime minister Boris Johnson included the establishment of a commission on criminal justice in his 2019 Queen’s speech, with the stated aim of improving the ‘efficiency and effectiveness’ of the criminal justice process, although it is unclear whether a looming crisis of representation is in scope.

Whatever the outcome of that commission, Lockley concludes that those involved in the creation of PACE can point to a legacy that will endure. The success of PACE, he notes, is secured by ‘the fact that nobody is left from pre-PACE days’.

Zander says: ‘Wherever you look at PACE, someone is always looking to change it, so the tinkering might go on.’ But he believes that, ‘despite various challenges, PACE is, and has been declared, fit for purpose – at least until another set of ministers initiates the next “fundamental review”’.

Dr David Cowan is a law academic and freelance writer

No comments yet