Two score and ten years ago, in the summer of 1972, the United States of America was riven with culture war. President Richard M. Nixon was fighting for re-election against George McGovern, who had emerged from the left of the Democratic Party. Nixon was campaigning on a platform of continuity (an orderly winding down of the war in Vietnam). But a vote for McGovern, Nixon supporters noisily claimed, was a vote for 'acid (legalised drugs), amnesty (of Vietnam draft-dodgers) and abortion'.

The alliterative slur was remarkable not just for its untruth but because it originated from the man briefly chosen as McGovern's own running mate, Senator Tom Eagleton. Much later, it emerged that Eagleton had coined the phrase - as a prelude to pointing out that when 'middle America, Catholic middle America, in particular', find out about McGovern's platform, 'he's dead'.

Middle America did indeed find out about it, or at least about the slur. That November, Nixon swept the polls, with the largest margin of the popular vote by any presidential candidate. He went on to serve nearly two more exceptionally tumultuous years in the White House.

Yet despite the power of the slur, it is hard to assert that abortion swung many votes in the 1972 election. Nixon was careful to sidestep the subject, though he was caught later as saying he believed abortion was 'sometimes necessary'. McGovern's stance, according to political commentator Timothy Noah, was that decisions were best left to individual states. This would have been a largely uncontentious stance. In his partisan history of the Supreme Court*, Professor Peter Irons concludes: 'Before the election in November, neither Richard Nixon nor his Democratic opponent, Senator George McGovern, made any mention of abortion.'

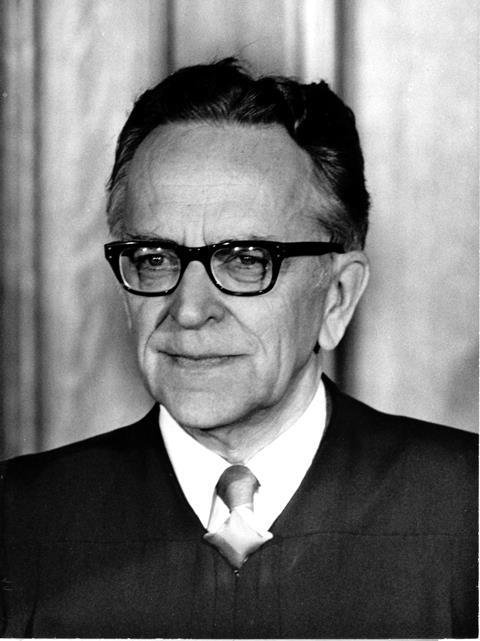

As we all now know, this ceasefire was about to fall apart. Proceedings in the Supreme Court case brought by Sarah Weddington and Linda Coffee on behalf of 'Jane Roe' to overturn a Texas statute defended by district attorney Henry Wade, had opened in December 1971. A second round of hearings took place the month before the elections, focusing on the 14th amendment to the constitution: 'No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens....'. But the storm did not break until the 'modest and unassuming' Harry Blackmun (a Nixon appointee, but only after the president's first two nominees had proven less than squeaky clean) delivered his ruling on 22 January 1973.

Blackmun opened in a contemplative mood, suggesting that attitudes to abortion might be influenced by 'one's exposure to the raw edges of human existence', before turning to historical and medical evidence. The crucial constitutional argument is shoehorned into two paragraphs, which conclude that the 14th amendment 'is broad enough to encompass a woman's decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy'. The bench agreed by a majority of seven to two.

With some understatement, Irons notes that Blackmun's opinion 'did not settle the abortion issue'. There is little doubt that the majority justices were running well ahead of public opinion - as they had with Brown v Board of Education. And opinion remains divided. This week the unprecedented leak of a draft Supreme Court opinion which would overturn Roe v Wade has reminded us that the use of the 14th amendment, and effectively the creation of a right to privacy, in order to legalise abortion is contentious and open to challenge.

Interestingly - though I haven't done the sums - coverage of the leaked opinion seems to have filled more column inches in the UK press this week than the original ruling did in 1973. This may be because it chimes with some our own cultural warriors, who can be smug that UK consensus on abortion, like that on the other great 1960s reforms, on the death penalty and homosexuality, were achieved through parliamentary democracy rather than judicial creativity. 'We're lucky that we live under the rule of law rather than the rule of lawyers,' Sam Ashworth-Hayes observes in The Spectator today. No doubt, if Roe v Wade is overturned, the dismal fallout will be upheld as a warning against any tendency of our own Supreme Court to take an activist turn, on assisted dying, for example.

But why, you ask, hark back to 1972? Politics is a bit like pop music: the stuff you experience as a teenager will always be the best. For this teenager, the '72 presidential race was when it all came alive: acid, amnesty and abortion were certainly more engaging topics than Ted Heath's dreary paen to something called the Common Market. As for drama, we didn’t yet know about Watergate, but for children of the sixties lurked the ever-present spectre of assassination.

When, 50 years ago next week, the news broke that presidential candidate Governor George Wallace had been gunned down at a campaign rally, I ran upstairs to put my favourite LP on the turntable, turning up the volume for the electrifying Southern Man.

'I heard screamin' and bullwhips cracking,' howled Neil Young, 'How long? How long?'

*Irons, Peter, A People's History of the Supreme Court, Penguin 1999.

2 Readers' comments