Russia must immediately suspend the military operations in Ukraine that it began on 24 February, the International Court of Justice ruled on Wednesday. Both countries must refrain from any action which might aggravate or extend the dispute between them, the United Nations court decided by a majority of 13 votes to two.

Was that an example of the international order at its finest, moving swiftly to secure a ceasefire? Or was it a sterile and pointless move that laid bare the limitations of international law? We may not know for some time.

The ‘provisional measures’ indicated by the court this week are comparable to an interim injunction: temporary but binding. They arose in a curious way.

Since 2014, Russia has accused Ukraine of acts of genocide against the Russian-speaking population in its eastern regions of Luhansk and Donetsk. On 21 February, Vladimir Putin described the situation there as a ‘horror and genocide, which almost four million people are facing’.

That’s denied by Ukraine, which wants the court to declare, under an international agreement dating from 1948, that there was no genocide and so no justification for an invasion.

Russia subsequently moved the goalposts, insisting that genocide was not its legal justification after all. Instead, it claimed to be acting in self-defence under article 51 of the UN charter.

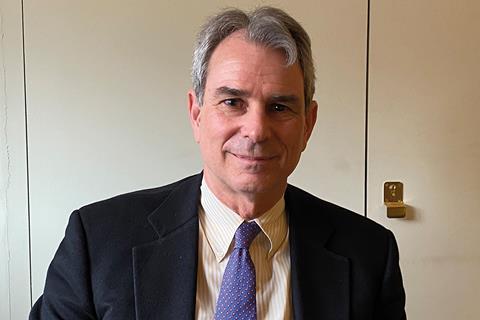

It’s true that countries such as the UK and the US have stretched the concept of anticipatory self-defence to cover, for example, the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in Iraq. But John Bellinger (pictured), who was legal adviser to the US State Department during the George W Bush administration and is now head of global law and public policy at the law firm Arnold & Porter, regards Russia’s actions as being on an entirely different level.

‘There’s nothing in UN history that compares to as flagrant a violation as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine,’ he told me during a visit to London this week. ‘This is essentially Nazi Germany rolling over its neighbours. Ukraine did nothing to provoke this.’

Didn’t that show that international law was essentially powerless?

Bellinger disagreed. On the one hand, Russia had violated article 2(4) of the UN charter, the cornerstone principle that requires member states to refrain from the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of another member state. On the other, he pointed out, international courts and institutions had immediately swung into action.

Two weeks ago, the UN Human Rights Council agreed to set up an international commission of inquiry into the violations and abuses that followed what it described as Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. The evidence it gathers will be fed into an investigation launched by Karim Khan QC, prosecutor of the International Criminal Court.

When Dominic Raab went to see Khan in The Hague on Monday, the justice secretary offered him financial and technical assistance – though Raab declined to say whether that would include access to military intelligence gathered by the UK.

On Wednesday, Russia was kicked out of the international body that enforces the European Convention on Human Rights. The Council of Europe, now down to 46 members, had regularly condemned Putin’s government for past breaches of the convention but presumably took the view that more could be achieved by keeping him on side. Russian courts could not sentence offenders to death, for example.

Bellinger observed that, despite everything, Putin was seeking to justify his invasion of Ukraine through the language of international law. ‘Is he doing this because he hopes to appeal to neutral countries like China or India? Or does he simply feel that it’s better to have some justification rather than none at all?’

That led me to ask whether the west was in any way to blame by condoning Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and allowing it to remain in the Council of Europe until now.

‘The west can certainly be faulted for acquiescing in Russia’s bad behaviour for the last 20 years,’ he replied. ‘Of course, it’s difficult to say what the alternative ought to be. Russia is, however you want to define it, a great power.’

But the European world order – perhaps the entire world order – was being remade right now. ‘When one of the five veto-wielding members of the Security Council violates the UN charter so clearly, it does call into question Russia’s membership of the UN and the UN Security Council. Is it appropriate for a country that has invaded one of its neighbours with such violence and force to be a central member of the UN system whose principal role is to guard international peace and security?’

Russia’s action may not precipitate a fundamental restructuring of the UN. It still has its veto. But, in the long term, it’s hard to see Putin getting away with this flagrant breach of international law.

joshua@rozenberg.net

No comments yet