A century ago, the solicitors' profession was remarkably sanguine about the arrival of the UK's first Labour government. In public, at least.

As usual following a general election, the Law Society's Gazette of January 1924 listed parliament's 28 solicitor MPs. Of course not one was Labour: notable names included Isaac Foot (the Liberal father of a future Labour leader) and the hardline Unionist Sir William Joynson-Hicks. And, of course 'George, Rt Hon David Lloyd, OM', two years after his fall as prime minister.

Labour's arrival in power with the minority government of Ramsay MacDonald, the illegitimate son of a farm labourer, went unmentioned. In its February edition, however, the Gazette found space for an effusive welcome for one member of the administration. In what passed for its news pages, it reported a unanimous Law Society resolution that 'the council have observed with great pleasure the appointment of the Rt Hon the Viscount Haldane to the office of lord high chancellor'.

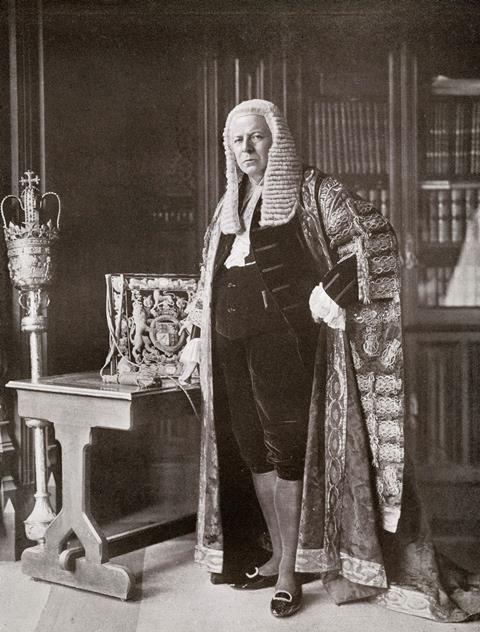

Viscount Haldane was Richard Burdon Haldane (1856-1928), the barrister and statesman who was in the thick of almost every major political and intellectual debate of his day. He had already served one term as lord chancellor, in the Liberal administration of 1912, before being hounded out of government for his supposed pro-German sympathies in 1914.

The Law Society's Council continued: 'They remember with gratitude the consideration which His Lordship invariably gave to the [Society's] representatives on questions affecting the profession which they ventured to address to him during his previous tenure of high office, and particularly they remember his great public services in connection with the simplification of the Law of Real Propety. The Council venture to congratulate Lord Haldane on his appointment, and to wish for him a successful term of office.'

It is easy to see why the Society clung to the new lord chancellor. As the only member of the new government with previous experience of high office, Haldane was a safe pair of hands alongside firebrands like chancellor Philip Snowden and the Fabian Sidney Webb, president of the Board of Trade. Haldane had a genuinely stellar legal record. He had taken silk in 1890, the youngest KC in 40 years, and had been by any standards an intellectual heavyweight, with a circle of friends ranging from Albert Einstein to Winston Churchill to Oscar Wilde. (Haldane was the first person to visit Oscar Wilde in prison, in June 1895, extracting a promise from Wilde that he would write 'something of worth'.)

Haldane had been drawn towards Labour because of the Liberals' failure to take seriously his passion for education reform. However he declined Ramsay MacDonald's offer of that portfolio, preferring to return as lord chancellor.

Yet, according to a recent biography* Haldane was never a socialist 'despite what some of his peers may have thought (and what the posthumously named Haldane Society for Socialist Lawyers suggests). He was just too practical to believe that a socialist regime could function.' Haldane himself set out his hopes in a letter to the poet Sir Edmund Gosse. 'If it comes off, I do not despair of being able to interpret to the country a new order of things which is bound to come anyway, and which will not be so very different from the old, but will form a further step in the self-evolution of the people.'

In fact the first MacDonald goverment did little for any new order: it lasted until 4 November. If the Gazette is anything to go by, the Law Society's main interaction with the Labour government was a grumble about the appointment of a barrister as solicitor to the Ministry of Labour.

In November 1924 following another general election, the Gazette published a new list of solicitors in parliament; just 17 this time. It did not find space to congratulate the return of George Cave (first Viscount Cave) as Conservative lord chancellor.

Haldane's death, in August 1928, went unremarked by the Gazette. But on 25 August the Solicitors Journal wrote: 'The time is not yet when the true value of the extensive and arduous work of the late Lord Haldane can be assessed with any degree of confidence; but no one can deny that he had won for himself a distinguished place among leaders in at least four distinct fields of activities, namely public administration, philosophy, education and the law.'

'His death is generally and sincerely mourned. There is lost to the state one of the greatest, most industrious, most cultured and most devoted of her servants.'

A rickety and inexperienced Labour administration was lucky to find a heavyweight elder to fill one of the great offices of state. Just possibly, history will repeat itself this year. But hard to identify an individual with one tenth of Haldane's gravitas in any of the main political parties today.

*Further reading: Haldane, the forgotten statesman who shaped modern Britain, John Campbell, Hurst & Co 2020

2 Readers' comments