Many unmarried couples are unaware of their lack of legal rights in the event of separation or death, but will a growing appetite for reform actually change ‘outdated’ laws? Marialuisa Taddia reports

THE LOW DOWN

Cohabiting couples are the fastest-growing family type in the UK, yet there is no legislation in England and Wales that adequately protects such couples on separation and death. Most still believe in the ‘common law marriage’ myth and are utterly unaware that they have few or no legal rights. The gap in the law has a particularly detrimental effect on the financially ‘vulnerable’ party – more often than not women. Calls for law reforms on cohabitation date as far back as 1984 when in Burns v Burns the Court of Appeal decided that the complainant had no right in the family property despite bringing up the children and contributing to household expenses. All of which means there is now a head of steam behind the 2007 recommendations of the Law Commission for reform. But will England and Wales bite the bullet and follow Scotland’s decision to protect the rights of unmarried people?

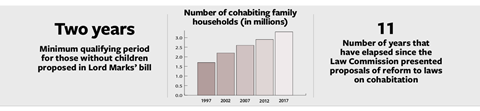

There were 3.3 million cohabiting families in 2017, more than double the figure in 1996. But few are aware of their legal rights – or rather lack of them. ‘Because there’s the myth of “common law marriage”, you have many people plodding along thinking “we’ve been together for 15 years and have three children, I’m obviously entitled to something”,’ says Susi Gillespie, a partner at solicitors Thomas Mansfield. But that is often not the case. For example, if the property is registered in one partner’s name, the other is ‘not entitled to anything, and even if their name is on it, they are entitled only to however much their interest is in that property’. By contrast, the starting point in a divorce is an equal division of the ‘matrimonial pot’.

Gillespie describes the legal treatment of cohabitees as ‘outdated’ and ‘discriminatory’ since it is often women who give up careers to care for children. In the event of separation or the death of their wealthier partner, they ‘could end up destitute’.

The available legal remedies are also out of reach for the less well-off. Lauren Evans, senior associate at City firm Kingsley Napley, says that disputes between cohabiting couples are on the rise, but solicitors only see ‘the tip of the iceberg’. Evans volunteers at Citizens Advice in central London, where she advises on disputes between unmarried couples who are ‘at a lower financial level than we see in the City’.

Even for those who can afford the legal fees, Evans notes: ‘The law is complex. To launch a property claim under trust law is expensive and leaves you at risk of paying the other person’s costs if your claim isn’t successful.’

Separating cohabitees who are property owners rely on the Trusts of Land and Appointment of Trustees Act 1996 (ToLATA). Under ToLATA, if the property is held in the sole name of one cohabitee, the burden is on the other cohabitee to show that there was a ‘common intention’ that they should have a beneficial interest in the property, and relied on that common intention to their prejudice. ‘That boils down to what someone says at a specific moment in time and who the judge believes,’ says Suzanne Todd, partner at Withersworldwide, London. ‘So that very much [depends on] someone’s credibility.

OGR Stock Denton partner Graeme Fraser says: ‘We end up with the bizarre situation where the courts look to [events] that might have happened years ago to actually infer or impute what the couple intended, which essentially is a bit of a fiction.’

Because there’s the myth of “common law marriage”, you have people plodding along thinking “we’ve been together for 15 years and have three children, I’m obviously entitled to something”

Susi Gillespie, Thomas Mansfield

Currently, Fraser explains, courts do not have the powers to order lump-sum payments or property adjustments ‘that are based on entitlements according to the length of the relationship or contributions that have been made to that relationship, whether in terms of looking after the family or the home.

‘The partner who looked after the children and the home but did not contribute financially is potentially left destitute because there are no claims available. It is a situation I have faced in practice.’

Cohabiting couples with children also rely on schedule 1 to the Children Act 1989. This allows an unmarried carer to apply for a court order to stay in the family home and receive periodic payments for the child, including a ‘carer’s allowance’, depending on the wealth of the father. Gillespie says the latter is ‘heavily monitored and courts go a long way to make sure there is no significant money left over for the mother, over and above what is required for the child’.

Furthermore, if the property is owned by the father in his sole name, once the child reaches 18 (or finishes university) ‘it reverts to the male ex-partner and the mother is left essentially homeless as there is no reversion of an interest to her’, Gillespie adds.

‘It’s very much focused on the child,’ says Todd. ‘Let’s say that you have been in a cohabiting relationship for 22 years and your youngest child is 19; then there is no protection under schedule 1 to the Children Act for you, so there is a huge lacuna there.’

And ‘if there aren’t any children at all, you then have to fall back on straight property law,’ says 36 Group barrister Andrzej Bojarski, referring to the use of the rules of trusts and proprietary estoppel in cohabitation disputes.

The House of Lords and Supreme Court (Stack v Dowden in 2007 and Jones v Kernott in 2011) have sought to adapt such rules to the ‘domestic context’, Bojarski says. ‘But the law was never designed to deal with that, and it certainly was not designed to deal with a full panoply of financial arrangements that arise when a relationship breaks down, because that focuses only on the ownership of a particular property rather than the issue of maintenance and pension, and anything else built up during the relationship.’

Bojarski also highlights inconsistencies in the legal treatment of cohabitees: ‘There is a recognition of the fact that there are cohabiting relationships that give rise to needs and responsibilities that [must] be met in the event of death, but they are not replicated in the event of a relationship breakdown.’

Under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975 a surviving cohabitee can make a claim against the deceased partner’s estate; and under the Fatal Accident Act 1976 cohabitees can claim for loss of dependency when their partner dies as a result of someone else’s negligence. In both cases the couple must have lived together (as man and wife or civil partners) for at least two years before death.

SCOTS GUARDS

Under the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006, cohabitees are given certain rights. Rachel Kelsey, a founding director of family law specialists SKO in Edinburgh, explains that such rights are ‘less than those for married people’ but they allow the courts to award a capital sum payment from one cohabitee to the other where there has been ‘financial disadvantage to one of the parties’. Furthermore, a surviving cohabitant can make a claim on the estate of their partner if they died intestate (and they are entitled to the same amount as a surviving spouse or civil partner). For both types of claim legal aid is available.

‘The act also introduced statutory presumptions about the joint ownership of household goods that were acquired during the cohabitation, and money put aside for household expenditure,’ Kelsey says.

In Scotland, there is no minimum period for cohabitation, and cohabitants are any couple living together as either husband and wife or civil partners.

‘There was a recognition that the law needed to be updated to reflect the reality of how people were increasingly choosing to live, and to make sure that they had some protection even if they were unmarried,’ Kelsey says.

But she acknowledges that ‘Scots lawyers and judges have struggled with these claims, which don’t sit within a balancing framework as divorce claims do’. For example, there is no requirement (as there is in financial provision on divorce) that the claims be ‘reasonable having regard to the resources of the parties’. Which means that ‘the cases have been very fact-specific and, as Scots lawyers, who don’t rely on precedent in the same way English lawyers do, we are still getting to grips with how to deal with them’. But a decade or so later lawyers are beginning to see ‘larger claims’ and ‘a less conservative approach’ being taken by the courts.

‘We have seen more people getting advice since the 2006 act and claims being made that couldn’t have been before,’ Kelsey says. But ‘there is still an education gap. It has begun to filter into people’s consciousness that there are rights that didn’t exist before. Sadly we have not yet managed – north or south of the border – to put to rest the “common-law marriage” unicorn.’

But the legal position of unmarried couples on death is far from ideal. ‘If there is nothing in the deceased person’s will granting [anything] to the partner they left behind then that partner has to apply under the 1975 act for financial provision out of their deceased partner’s will,’ says Gillespie. By contrast, in a marriage there is ‘automatic protection’ for the surviving spouse.

Cohabitees are excluded from the class of persons who will receive a share of the estate under intestacy rules, although they can make a claim under the 1975 act. But, Gillespie says: ‘You could have a situation where if the unmarried party dies intestate and they had children, the child would inherit and the partner could be penniless.’

Furthermore, only spouses and civil partners are entitled to bereavement damages under the Fatal Accident Act; and unless they are nominated as beneficiaries, cohabitees have no automatic entitlement to claim a share of their former partner’s occupational pension.

Two recent Supreme Court judgments have shown UK cohabitation law to be in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights. In Siobhan McLaughlin for Judicial Review (Northern Ireland), the UK’s highest court ruled that unmarried couples should have the same right as married people and civil partners to claim for state benefits such as bereavement payment and widowed parent’s allowance. In Denise Brewster for Judicial Review (Northern Ireland), it was held that Ms Brewster was entitled to her late long-term partner’s occupational pension despite the fact she had not been nominated to receive one.

‘These are positive decisions, but they are very often case-specific and there would have to be a legislative change to make them apply to everybody,’ Gillespie says.

With the help of solicitors, cohabiting couples can enter into cohabitation agreements and ‘declarations of trust’.

‘They are likely to be upheld and have weight, but they have to be done on a voluntarily basis,’ Fraser says, pointing to the small proportion of unmarried couples with such agreements.

The landmark case that started calls for reform was Burns v Burns in 1984, in which the Court of Appeal acknowledged that ‘over a very substantial number of years’ the complainant ‘may have worked just as hard as the man in maintaining the family’. But the court decided that she had no beneficial interest in the property because there was no ‘common intention’ of joint ownership.

In 2007, the Law Commission recommended legislative reform in a report which concluded that the law was ‘complex’ and produced ‘unfair outcomes for cohabitants’.

Fraser, Resolution’s national spokesperson on cohabitation, says: ‘It is a thoroughly researched report and it still stands up.’

The commission did not agree that cohabiting couples should have ‘access to exactly the same remedies as married couples and civil partners’ and recommended a ‘scheme’ of financial remedies that would empower the courts to make a ‘range of orders’, such as lump-sum payments, property transfers and settlements, and pension sharing (but no periodical payments, unlike on divorce).

The statutory scheme would only be available to eligible cohabitees, such as those who have had a child together or have been cohabiting for a minimum number of years; and it would require applicants to prove that they had made ‘qualifying contributions’.

‘The applicant would have to show that the respondent retained a benefit, or that the applicant had a continuing economic disadvantage, as a result of contributions made to the relationship,’ according to the commission, which also made recommendations for reforming the statutory remedies available on the death of a cohabitant under the 1975 act.

Efforts to introduce legislation on the back of the report have so far floundered. These include a private member’s bill introduced in the House of Lords in 2008 by Lord Lester of Herne Hill (Anthony Lester), followed by three attempts by Lord Marks of Henley-on-Thames (Jonathan Marks), the last of which was in July 2017. The Cohabitation Rights Bill has since been stuck in parliament awaiting a second reading in the Lords on a ‘date to be announced’.

In this, England and Wales lags behind other jurisdictions including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Sweden and Scotland (see box) that have introduced similar statutory schemes for cohabitants to those proposed by the Law Commission.

The commission’s approach and the current bill broadly reflect the position of Resolution, which has long campaigned for the rights of cohabiting couples.

For example, Lord Marks’ bill proposes that the minimum period for those without children might be two years, which Resolution says is ‘consistent with the qualifying period for the Inheritance Act’. But Resolution says courts should also have the power to make orders for ‘childcare costs’ to allow the primary carer parent to work. Other points of agreement include allowing a surviving cohabitant to apply for bereavement damages and giving cohabitants an insurable interest in each other’s lives.

Gillespie, a member of Resolution’s central committee for cohabitation and equalities, says the Cohabitation Rights Bill, unlike the law on divorce, contains no presumption of equal sharing, nor does it propose the introduction of maintenance payments.

‘It is more a question of courts having more flexible powers in relation to property ownership, and to order the payment of a lump sum, so that there is some redistribution of money to reflect the contributions been made during the relationship,’ says Fraser.

Lord Marks’ bill and Resolution state there should be the opportunity for cohabiting couples to opt out of the scheme. ‘That is trying to keep everybody happy: the opponents of the legislation and those who are supporting the sanctity of marriage,’ says Gillespie. ‘You have to recognise that there are couples that don’t want the state to interfere.’

It is unlikely new legislation will be introduced soon. It is not a priority for the Ministry of Justice. ‘For a bill of this nature to succeed would take years,’ says Fraser, pointing to the ‘complexity of drafting’ such legislation since ‘cohabitation affects so many areas of law.’

I am hoping we’ll be able to generate publicity and use Steinfeld and Keidan as an opportunity to educate the public about the lack of rights cohabitants have

Lauren Evans, Kingsley Napley

Bojarski observes: ‘Anything seen as potentially devaluing marriage or encouraging people not to marry because they have remedies elsewhere does seem to discourage parliament from doing anything about it.’

Still, Bojarski adds, if there were a case showing ‘the hardships of the laws as they are at the moment, that may provide the sort of foil needed to build the campaign around it’. He points to July’s Supreme Court decision in Owens v Owens (in which the wife was not granted a divorce despite the unhappy marriage, because she could not prove that her husband was at fault). That ‘gave a nice focus to the campaigning group’ and ‘gained credence in the media’, ultimately leading the government to commit to reforming the law on divorce.

Another recent Supreme Court decision (Steinfeld and Keidan v Secretary of State for International Development) was behind the government’s decision to extend civil partnerships to heterosexuals. But this is a double-edged sword for cohabitation law reform.

For Evans this is ‘fantastic news that’s really the springboard to deal with raising awareness about cohabitants. I am hoping we’ll be able to generate publicity and use it as an opportunity to educate the public about the lack of rights cohabitants have’. She adds that ‘a proportion of cohabitees who are disillusioned with marriage’ may opt for a civil partnership when it becomes available to heterosexuals.

But Fraser warns that ‘it is important we don’t confuse the picture’, arguing that extending civil partnerships to opposite-sex couples will never be a substitute for cohabitation law reform. ‘We are still going to see many people who are living together, but for whatever reason they don’t want to marry and are probably not going to enter into a civil partnership arrangement,’ Bojarski concludes. ‘And they are still going to be left outside the law at the moment.’

Marialuisa Taddia is a freelance journalist

5 Readers' comments