Just one in five law firms remains a traditional partnership, so how are the ‘disruptors’ measuring up? Grania Langdon-Down finds out.

The legal services market is undergoing unprecedented structural change as disruptive business models emerge that are leveraging new technology to challenge their traditional rivals.

So what business models are the 10,408 law firms in England and Wales using as they fight to retain their territory?

Alternative business structures (ABSs) hit a new milestone at the start of this year as the number across the legal sector reached 1,130, with 60% (697) regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority (see In Numbers box, p20).

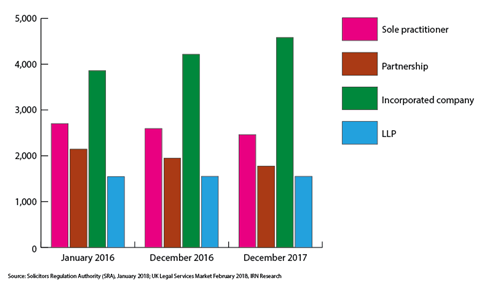

At the same time, the latest review of the legal services market by IRN Research has found that 44% of law firms are now incorporated companies. A further 15% are limited liability partnerships (LLPs), with just 17% – 1,777 firms – still traditional partnerships. The remaining 23% – 2,462 firms – are registered as sole practitioners.

Predictions that the number of law firms would fall in the wake of ABSs have proved unfounded, according to the IRN report. There have been some large closures, downsizing in many firms and the dropping of underperforming practice areas. But new boutiques and virtual firms have emerged, with numbers of law firms stabilising and indeed up 0.5% on the previous year.

It is now six years since the SRA licensed the first three ABSs, in March 2012.

First up was John Welch & Stammers (JWS), a traditional three-partner Oxfordshire general practice. It wanted to make Berni Summers, practice manager for the previous 12 years, its first non-lawyer managing partner.

Next in line was Co-operative Legal Services – seen as a pioneer of the new wave of non-legal entrants attracted to the sector. That firm saw multi-million-pound losses in the early years, leading to an admission that it grew ‘too fast’ and rapid retrenchment.

Nearly 700 ABSs later, has the market developed in line with the original Clementi proposals?

Addleshaw Goddard (AG) partner Jon Cheney specialises in advising professional services firms, including UK and overseas law firms. ‘The ABS regime has been more liberal than originally proposed, leading to more creative ownership structures and delivery models than may have been anticipated,’ he says. ‘However, the availability of ABS structures has not been the catalyst for the “Big Bang” in the legal market that some predicted [that term was used by former justice secretary Ken Clarke in 2011]. Regulatory liberalisation has inevitably increased pressures on the pricing and delivery of legal services.

‘But the introduction ABSs coincided with the recession so, while they may have accelerated the pace of change in the legal market, ABSs certainly didn’t cause it. Also, innovation and consolidation are generally positive forces in most markets.’

Alan Radford, partner and professional practice specialist at Browne Jacobson, says there are issues still to be resolved. ‘The SRA certainly believes that its liberalisation of business models will result in greater investment through alternative sources of capital,’ he says. ‘It has in mind IT infrastructure, which can be very expensive and, frankly, beyond the means of many SME firms.

‘However, outside ownership poses problems for solicitors because of conflicting duties. The classical firm or limited partnership model does not carry with it the same tensions as a firm where solicitors are employed by a company which has investors. To whom is the primary duty owed – the client or the shareholders? Again, we probably haven’t seen this model of operation in place long enough in order to see how that dilemma will resolve itself.’

The Legal Services Board’s analysis last year of investment in legal services since the introduction of ABS licensing suggested that external capital is not used as much as might have been expected. The report suggested that the use of capital might be down to cultural attitudes – for instance, lawyers are reluctant to cede control of their businesses, preferring instead to rely on profits and reserves, or bank lending. The research also indicated that there were no significant regulatory barriers to investment, while the cost of legal services regulation did not appear to be a barrier either.

The Law Society is broadly supportive of ABSs, arguing they provide choice for solicitors and clients. However, Law Society president Joe Egan stresses: ‘It is important that solicitors are able to operate on a level regulatory playing field and that client protections remain prioritised. This means applying rigorous scrutiny to the suitability of ABS owners, making sure that ABSs have the same scrutiny as ordinary law firms, and ensuring proper public and consumer protections so clients have the same safeguards regardless of what type of firm they instruct.’

The Society also wants more analysis of the impact of the ABS on access to justice. Available data suggests that ABSs tend to set up in commercial and non-contentious practice. The only area of litigation into which ABSs have made a significant advance is personal injury work.

There have been some high-profile crises among ABSs, including at Parabis group, which went into administration in November 2015, and Slater and Gordon, whose well-publicised travails triggered a massive restructuring. But specialists in professional practice say those problems arise out of business decisions rather than stemming from an ABS structure. They add that being an ABS does open up opportunities.

New kinds of law firm

Keystone Law, established in 2002, was one of the first networked law firms. It converted to an ABS in October 2013 and had a £3.15m cash injection from private equity firm Root Capital the following year. Since then, Keystone has seen significant revenue growth and, in November 2017, became the third UK law firm to list on the London Stock Exchange when it joined the Alternative Investment Market (AIM). The firm had a market capitalisation of £50m following an oversubscribed £15m fundraising.

Keystone’s managing director James Knight says there was no ‘grand plan’ when the firm converted to an ABS: ‘We didn’t know whether or how we would use the new freedoms. However, it seemed a good idea to have them in the back pocket. And only a year later we did find it was necessary.’

Charles Stringer, the finance director who started the firm with Knight and became a co-director and shareholder after Keystone became an ABS, retired in 2014. Root Capital purchased the majority of his shareholding, becoming owners of a 35% stake.

‘When we floated on AIM it was not because either I or the private equity firm were looking to exit,’ says Knight. ‘We also didn’t need to raise funds for expansion as Keystone was already profitable.

‘We believed it was a good thing for the longevity of firm and provided a more substantial base. It means when Root Capital does want to sell, the public market will be able to accommodate that.’

He believes it is better for a law firm to have many minority shareholders than one significant minority shareholder. ‘Relations with Root Capital are extremely good and very beneficial to the firm,’ he says. ‘I have no regrets whatsoever in getting them involved, but you can’t always guarantee you will be lucky twice.

To float or not

The other significant reason for flotation was, he explains, to ‘enhance the reputation and brand of Keystone. It gives the increasingly sophisticated clients we engage with a greater sense of security and trust, bearing in mind the public process of floating a company is incredibly difficult and expensive. By and large, public companies are a safer bet as they are more regulated, more accountable and there is greater transparency on their financial activities.’

The only reason JWS became an ABS, says Summers, was so she could become a partner; it made the difference between her staying and going.

‘I don’t think I can say, hand on heart, that being an ABS has made a huge amount of difference to this practice,’ she says. ‘But I do think, in years to come when I go, it will potentially make a huge difference because the firm will be able to attract an all-rounder interested in the partnership potential.’

So should firms have a grand plan to convert to an ABS? Kingsley Napley partner Iain Miller, an expert in legal regulation, says: ‘There are good strategic reasons for doing it. Many firms will have directors of finance/HR they may want to reward by making them equity partners. It also gives more flexibility in this evolving world if an opportunity comes up where someone wants to invest in the business and do a joint venture.’

Paul Bennett, partner in Aaron & Partners professional practices and employment team, says some high-profile failures among ABSs have ‘tainted’ the model. He points out that Aaron & Partners’ insolvency team has helped on a few of the failures and the causes are the same as for non-law firms: overexpansion, not managing risk effectively and running out of cash.

‘There is no perfect model but ABSs are a good option when used sensibly,’ he says.

Does a firm’s culture or management style need to change with becoming an ABS? ‘That depends on the firm,’ says Mark Briegal, Aaron & Partners’ head of professional practices. ‘We are an ABS as our finance director and, previously, a chief executive were members of our LLP and we wanted to include senior managers in the running of the firm.

‘It has not affected the culture of our firm as we have always regarded ourselves as professionals. Where there are outside investors, that may alter the culture, but that is why the ABS is set up.’

Insurance

There are professional indemnity insurance (PII) issues that come with converting to an ABS from a traditional partnership model, including an additional £1m of cover.

Brian Boehmer, partner in Lockton’s global professional and financial risks division, says this could impact the firm’s premium cost, but it would be ‘quite modest’ compared to their current spend.

‘When ABSs were first introduced, there was a little apprehension and caution among insurers,’ he says. ‘But, today, most of the leading participating insurers have no issues with it.

‘There are, however, greater concerns when a firm wishes to become a multidisciplinary practice. Depending on the disciplines adopted within the ABS, placing cover could be challenging, particular if the ABS wishes for all components, facets and/or divisions of the organisation to be covered with one single insurer.’

This type of ABS will have multiple regulators to satisfy and not all participating insurers can or will write the different businesses that can fall under an ABS, he explains. Independent financial advisers and surveyors with survey and valuation exposures are two of the more challenging areas.

One of the common questions posed by insurers, he says, is: why are you converting?

‘If the answer to this question is that the firm wishes to promote another professional to a leadership function, this is often viewed very positively by insurers.’

What can shock those converting to ABS status, says Bennett, is the SRA’s enforcement approach and ABSs’ exposure to fines of up to £50m – not the £2,000 maximum for a traditional partnership.

‘The disciplinary regime differs as well. The SRA has the power to direct disciplinary matters to one of their adjudicators. As one of a handful of lawyers to have won an adjudication for clients, I can say it is tougher than successfully defending a Solicitors Disciplinary Tribunal case because the burden of proof is set at the civil standard.’

But, he says, a well-run firm should have no concerns: ‘At Aaron & Partners, we aren’t concerned about higher financial exposure because we are comfortable the risks are properly managed. I think the benefit of involving non-solicitor members in the management team has worked for us. Our marketing is sharper and it is good to have people with a bit of “skin in the game”, which raises performance.’

DIFFERENT STROKES

AG partner Jon Cheney sets out 10 examples of different ABS models

- New corporate entrants to the legal services market, which complements their existing service offering – including well-known brands, such as Co-op Legal Services and AA Legal Services – sometimes in collaboration with an established law firm (Lyons Davidson, for example, has entered into a number of joint venture arrangements).

- Consolidators – often providers of more ‘commoditised’ consumer legal services – Slater and Gordon is perhaps the best known brand.

- Commercial law firms with regional coverage and ambitions to grow – for example, Gateley (which has listed) and Knights (which took external private investment).

- Providers of integrated professional services – accountancy firms, notably the Big 4, offering legal services but also law firms providing accountancy, consultancy and other services, such as Gordon Dadds, one of three UK AIM listed firms (along with Gateley and Keystone).

- Niche firms with an track record of profitability and/or the potential to expand – such firms will often attract private equity investment (such as Keoghs with LDC and Stowe Family Law with Livingbridge).

- Local authorities – creators of joint ventures to satisfy their own legal needs and to provide services to other councils and private businesses, such as Kent County Council’s Invicta Law.

- Innovators of alternative legal service provision – for example, the flexible platform offered by AIM-listed Keystone.

- Collaborations between different branches of the legal profession – for example, between solicitors and barristers and between solicitors and patent/trade mark attorneys).

- Law firms which wish to issue equity to senior non-lawyers – such as a finance director, head HR, marketing, IT etc.

- Overseas law firms – UK partnerships controlled by an overseas parent comprising foreign lawyers who are not RFLs.

The process of getting an ABS licence has become more streamlined since 2012, says Miller, so firms ‘shouldn’t be scared to do it’. It now takes an average of 1.4 months for the SRA to license an ABS, though more complex applications will take longer. Some ABSs are said to have asked the regulator to defer issuing their licences because they were processed too quickly for other business arrangements.

When it comes to converting to an LLP or incorporating as a limited company ‘culture and tax’ generally tip the balance between the two, says Aaron’s Briegal.

‘Firms are tending back towards LLPs since the introduction of a dividend tax, as the tax advantages of being a limited company have mainly gone,’ he says. ‘LLPs are much more flexible in terms of capital and incoming/outgoing partners. There’s also a more collegiate feel, which suits more traditional law firms. The limited company tends to work for volume practices.’

Incorporation and ABS structures generally have a positive impact on management structures for firms of all sizes, believes Viv Williams, consulting director of Symphony Legal.

‘The distinct advantage of incorporation into a limited company is the sale of goodwill,’ he says. ‘It is hard to realise goodwill if you are selling or merging to another law firm. But, by selling your firm to yourself, the goodwill can be recognised. HMRC will recognise anywhere between three to five times gross profits as goodwill on the balance sheet and, although this value is not real money, this can be converted into directors’ loan accounts and drawn down by the directors.’

Savings are not as high as previously because of the withdrawal of entrepreneurs’ relief in 2015, he says, but, for many firms, they are still significant.

When it comes to tax liability, he says capital gains tax (CGT) on incorporation can be deferred and spread over up to eight years.

‘This means therefore that the cashflow doesn’t suffer – on the contrary, the tax savings will outstrip this negative CGT and can give a positive cashflow to the firm,’ he says.

He gives the example of a two-partner firm which will make tax savings – after the CGT payable on the goodwill – of £1.4m over the first 10 years, with savings per annum (pa) at a lower level thereafter. These figures are based on profits of £680,000 pa and current drawings/capital levels.

AG’s Cheney says it is possible to reinvest money in a firm more tax-efficiently as a limited company than as an LLP, adding that firms now operating as companies often cite this as one reason why the structure is working better for them.

Demise of traditional partnerships?

HMRC’s introduction of the salaried member rules for LLPs in the Finance Act 2014 made some firms question whether LLP was the right structure for them, Cheney says. But it would be very rare to start a new business as a traditional partnership, he notes. ‘You would almost certainly become an LLP, partly because of limited liability. But also, an LLP is a body corporate, just like a company, which means it can contract in its own right and hold assets, such as the firm’s lease, making it a very efficient structure.’

Good PII cover and management are certainly critical, says Briegal. ‘LLPs offer more security than a traditional partnership, but there are still risks in the event of insolvency – for example, up to two years’ drawings can be clawed back by a liquidator if they have been taken while the members knew the LLP was struggling. It should be possible to limit personal liability for negligence if all advice is given by the LLP.’

So are there still benefits to being a traditional partnership?

‘No,’ says Briegal, ‘unless you are into absolute secrecy.’

IN NUMBERS

At the end of 2017, there were 10,408 regulated law firms in England and Wales – up 0.5% on 2016.

- 85% of law firms have four or fewer partners.

- 23% of firms are sole practitioners.

- The top 200 law firms account for more than 50% of private practice revenues.

- 44% of solicitors firms (4,580) use the incorporated company model (see bar chart).

- LLPs account for 15% (1,551) of law firms.

- Traditional partnerships make up 17% (1,777).

- As of January 2018, there were 1,130 ABSs: 697 regulated by the SRA; 326 by the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (solely to provide probate services); 61 by the Council for Licensed Conveyancers; 40 by the Intellectual Property Regulation Board; and 6 by the Bar Standards Board.

Source: IRN Research’s UK Legal Services Market report, February 2018

Bennett agrees. ‘It’s simply a model with a higher level of personal risk. It’s bonkers to operate this way in 2018 and has been since 2002, when LLPs were created. If anyone reading this is in a traditional partnership, they should take advice and protect their assets rather than continue without any benefit. It does not need to be complex because the LLP option is a great model.’

However, the advantages of an LLP do not suit every firm. JWS, which dates back to 1932, is a ‘very old-fashioned traditional equity partnership’, says Summers. ‘Becoming an LLP would just mean more red tape. There is also no such thing as limited liability because you just have to do personal guarantees.’

One of the most well-known traditional partnerships is magic circle firm Slaughter and May, founded in 1889. It currently has 111 partners, 804 lawyers and 1,338 staff across four offices – London, Brussels, Hong Kong and Beijing.

Practice partner David Wittmann is responsible, together with the firm’s senior partner, for developing and promoting the firm’s practice.

‘It is important that our partners are owners of the business,’ he says, ‘as that helps empower them and gives them the authority and responsibility to grow their practice and build the firm generally. It ties in to our lockstep model which, taken together, drives a collaborative culture. It means people are incentivised to work together and think about what is right for the firm without silos or jealousies.’

Being an LLP or company requires regular publication of financial results. That means lots of outside analysis that may push a firm into taking a more short-term approach, Wittmann argues, rather than ‘what is right for your clients and your market reputation’.

Confidentiality – particularly financial confidentiality – is certainly one reason for being a traditional partnership, says Cheney.

‘Let’s face it, the legal press is always fascinated by how much partners in law firms earn. While no one can verify profits at firms which aren’t required to file accounts, the press still provides pretty good guidelines.’

For Williams, the traditional partnership model is no longer ‘fit for purpose’ for most firms and will gradually disappear from all but the top 10 firms, where PEP is still a significant element in retaining it.

The question then will be how firms manage to align the benefits and ethos of a collegiate partnership with the demands of a more corporatist model.

UBERNISATION - OPPORTUNITY OR THREAT?

Law firms may soon face a new challenge to their business models after the SRA signalled what has been described as the ‘Uberisation’ of the legal market.

The regulator is proposing to relax the rules on practising to create the role of the ‘freelance’ solicitor, able to offer unreserved legal services to the public without being required to work through an authorised firm or register as a sole practitioner.

The new status will come with conditions. ‘Freelancers’ won’t be able to hold client money, for example, but the SRA argues there is as a huge alternative market emerging and its current rules stop solicitors from operating in it.

The Law Society and practitioners specialising in professional practice suggest firms could respond to the new competition by splitting off their reserved legal activities into one entity and the rest of their work into another to reduce regulatory burdens. The concern is that it is more likely that bigger firms could potentially take advantage of the changes. Small firms will have less flexibility to split off their reserved and non-reserved work into separate entities, potentially leading to market consolidation and less consumer choice – contrary to the SRA’s original aim to increase market competition and consumer choice.

Browne Jacobson partner Alan Radford says: ‘In theory, it should be easy for a firm to open up a second company to handle non-reserved activities and, because the regulatory burdens should, in theory, be less, to do so at a lower price.

‘I think only a few firms will take that step – the majority will wait to see what mistakes are made by anyone brave enough to innovate in this way.’

Crispin Passmore, the SRA’s executive director of policy, says much has still to be decided. ‘But it is time to end the “fiction” of the “non-practising” solicitor employed by an accountant sitting in the same room as the client, but technically advising the accountant not the client.’

He thinks it unlikely firms will split their businesses. But he says: ‘I would have no concerns if they did it as long as no one is misleading clients. What you can’t do is say “come to us” as a regulated law firm and then give advice through an unregulated business with the same name and the client doesn’t know.’

For Aaron & Partners’ Mike Briegal, it could be a positive step: ‘It should help as solicitors can be in partnership with other specialists and it should therefore make their businesses more effective.’

Grania Langdon-Down is a freelance journalist

No comments yet