You cannot change the past. But history is always changing, and as a discipline this is what makes it exciting. History changes through revelations about the past uncovered through the emergence of new evidence, and it changes through a reassessment of what we already know. We change our view of historical events depending on the evidence we decide is relevant to our enquiry, and which evidence should be discarded. History also presents, perhaps a little too easily, as ‘stories’ to which we become attached.

My heart beats a little faster on reading the word ‘history’ and many Gazette readers I know feel the same way. So for the curious among us, hurray for Black History Month, which should have a special link to our study of the law and the legal profession, and the history of both. There is testimony and data which insufficient time has been spent examining and publicising. If you love history and are interested in the law, that means we are at the start of an exciting period. It is a process aptly dubbed ‘an unforgetting’ by comedian Lenny Henry in a recent documentary.

There is a celebratory theme to some of what is done each October in Black History Month. The individuals with achievements, including ‘firsts’, are publicised. This is important – a rebellion against the condescension of a very uniform-looking posterity.

An important starting point for many could be the material brought together in Debo Nwauzu’s Black Lawyers Directory (BLD) project. There, in its history section, is a list of people who achieved success against the fierce headwinds of racially unequal contexts.

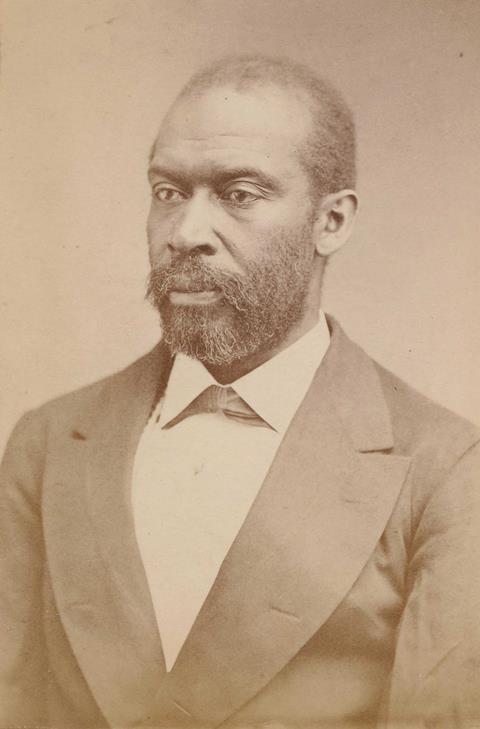

Here, we can unforget Thomas Morris Chester (pictured), the son of an escaped slave born in the US in 1834, believed to have been the first African American to qualify as a barrister in England. He was admitted to Middle Temple in 1867 and was called to the bar in 1870. Or Christian Frederick Cole, son of a Sierra Leone clergyman, called to the bar in 1883.

Better known is the predominance of Indian independence leaders, shaped by Cambridge colleges and the Inns, and lawyer Nelson Mandela. And there are black lawyers who achieved ‘firsts’ which occurred in my lifetime. Paul Boateng, first black cabinet minister is one. Patricia Scotland, first black (and first woman) attorney general, is another.

And if marking people’s lives and achievements is not important, why are law’s grand buildings so full of expensively framed portraits? Why does the display window of Wildy’s shop promote lawyer biographies?

Such publicity also serves history. Publish a list and more names emerge – often linked. In this vein the BLD, mostly composed of high-flying current lawyers, started as a thin volume. By 2015 it numbered hundreds of entries. Better data, more links, more stories.

Work on the complex relationship between race and the law itself has seen a surge in good published work. This year Nicholas Rogers’ Murder on the Middle Passage, The Trial of Captain Kimber concerns the 1792 five-hour trial of captain John Kimber for the murder of a slave girl (he was found not guilty). At University College London, the ‘slave ownership database’ and research on the Slave Compensation Commission (echoes heard in the MoJ’s penchant for ‘compensation portals’) feels important.

The story told by Rogers is a theme that emerges again and again. The grand promises of our justice system – the fine words of Magna Carta – hang in earnest over a system where key actors and established laws conflict with the guiding aspiration. That disconnect informed the arguments of the Empire’s legally trained independence campaigners, as it did lawyers (both black and white) who fought Apartheid.

To complete the picture, there is good work to be done on the history and significance of the networks and associations that both link and sit behind the individuals we celebrate as having achieved ‘firsts’. Extensive academic work on the centenary of women in the law shows how networks and activism precede progress towards equality.

So the Black Solicitors Network is an important part of this story, as is the more recently established Black Barristers Network. Networks that centre on the work of David Lammy MP, urging professional and law and justice reform, will be seen as key. The creation of the Law Society’s Ethnic Minority Lawyers Division in 2015, replacing an informal forum, is a recognition that networks and activity are both a precursor to progress and a way of defending it.

Added to the exciting evidence for future historians is the data gathered by the SRA and the MoJ on the legal profession’s composition – by gender, race and social background. This has been done relatively recently, but data gives context to testimony. It so far seem s to show progress on access to the profession, especially in the past decade, but a chequered record on equal promotion thereafter.

When the Society library reopens, I would also expect a painstaking check of the undigitised Gazette archive to yield surprising and interesting reports, as it did for our women in the law centenary coverage. The past does not always explain the present – that is a glib assumption. But our knowledge of history – in this case the role of the law and lawyers in it – informs how we see the world, and to a degree how we act in it.

Leslie Thomas QC told me earlier this year, as we discussed the Black Lives Matter movement and events since the death of George Floyd: ‘There was something different here… this isn’t dying down.’

I cannot think of a better time to be curious about the history – and law, lawyers and the legal profession’s role in it.