Richard Wilkinson

£25, I.B. Tauris

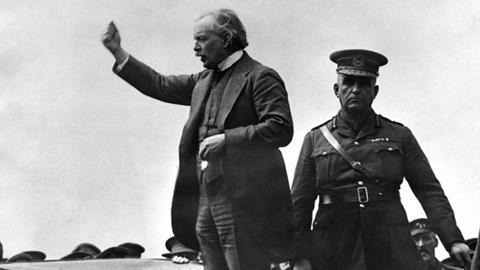

Only one solicitor has ever become prime minister of the UK. You can find his portrait in the lobby of the Law Society’s HQ in Chancery Lane – so long as you take a sharp left at the entrance and look behind a pillar. I have long suspected the positioning to be deliberate: fans of David Lloyd George (1863-1945) can be assured he hangs in a place of honour. But those who might have wanted him literally hanged do not have his presence thrust in their faces.

The title of this well-researched biography says it all; note the lack of question mark after ‘scoundrel’. Most of Lloyd George’s contemporaries would have had no trouble labelling him both. Now, to the known charge sheet of serial adultery, hypocrisy over military service, the sale of peerages and the mutually preening meeting with Hitler, Richard Wilkinson adds revelations of sexual assault. There is even a living witness, the redoubtable Jean Trumpington, who recalls as a second world war land girl: ‘The old goat would stand me up against a wall, take out a tape measure and try to take all my measurements.’

Wilkinson wonders why none of this got out in the Welsh Wizard’s lifetime. The short answer is that it did, both within the political elite – Churchill, for example, must have known of Lloyd George’s virtually bigamous relationship with his secretary – and the wider population. That the popular press did not make more of a meal of it is partly down to Lloyd George’s knowledge of, and frequent recourse to, the libel laws and partly out of lingering respect for his achievements as a radical chancellor and as the prime minister who won the war.

As for Trumpington’s charge, we do not need to go back to the 1940s to find a time when such behaviour by dirty old men was, if not ever acceptable, at least unremarkable.

But this biography does much more than tap into the #metoo spirit. At a time when (in England, at least) it is possible to shine at A-level history with only the vaguest idea of who Lloyd George was, any new biography is welcome. Especially as, Wilkinson alleges, previous biographers ‘most of them male and/or Welsh, have been too kind’. For his part, Wilkinson is at pains to be fair, especially over the conflict with General Haig over the conduct of the Great War.

And, while even the kindest of hagiographers would not have described Lloyd George as a feminist, Wilkinson gives him credit for a memorable line on coming round to supporting votes for women: ‘When one sex has rather conspicuously failed in some of the essentials of good government , I think we might try a partnership of the two.’

Overall, there can be no contesting Wilkinson’s verdict that David Lloyd George was a ‘fascinating hero with glaring flaws’. But it may be a while before that portrait in Chancery Lane is moved to a more prominent position.

Michael Cross is news editor at the Law Society Gazette

1 Reader's comment