Kazakhstan is enjoying an economic boom but politics plays a big part as lawyers seek to carve out practices.

Since the collapse of the former USSR in the early 1990s, Kazakhstan’s economy has seen its GDP rise meteorically, reaching an all-time high in December 2012 of $202bn. In the first six months of 2013, GDP grew by a further 5.1%. This phenomenal growth is largely due to its wealth of natural resources. In addition to Kazakhstan being the largest producer of uranium in the world, the discovery in 2000 of recoverable crude oil around the Caspian Sea in the Kashagan oil field, and the more recent discovery of gas reserves, have served to heighten international interest.

The Kashagan field, together with Tengiz, Kazakhstan’s largest onshore field, account for much of the nearly 4 million barrels of oil a day production that the US Energy Information Administration believes that Kazakhstan will reach by 2040. British Aerospace (BAE), BG Group and Shell are among the British companies which have invested in the market.

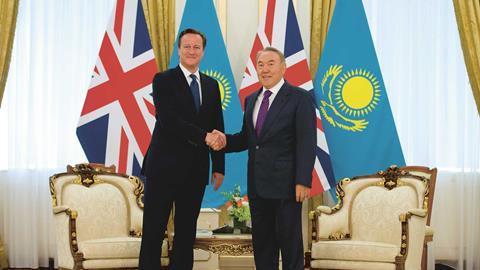

David Cameron’s visit to Kazakhstan in the summer, during which he described the country as ‘one of the rising economic powers of the world’, was the first visit to the country by a serving prime minister, further underlining the importance of this central Asian country on the international stage. Accession to the World Trade Organisation is imminent.

A new hub in Astana

The interest of overseas investors has inevitably led to a growing number of international legal advisers looking to set up a presence in Kazakhstan. Up to now only a handful of law firms have had an office in the country, usually in the commercial hub of Almaty. These include Baker & McKenzie – CIS Ltd, Morgan Lewis, Dechert, Norton Rose Fulbright and Dentons. The last few months, however, have seen new entrants to the market, such as central and eastern European firm Kinstellar, which opened its first office in Almaty.

Others, meanwhile, have looked beyond Almaty and now have offices in the Kazakh capital, Astana. White & Case launched its second Kazakh office in the capital in October. A few months earlier, Dentons, which also already has an Almaty office, opened a satellite office in Astana. In a statement, Dentons’ Europe CEO Dariusz Oleszczuk explained his firm’s reasons for broadening its Kazakh presence: ‘Kazakhstan is a rapidly growing economic hub in the CIS region, so strengthening our capabilities and presence in this country is of strategic importance to us.’

While Almaty remains the major business and financial hub, Astana has been the country’s capital since 1997 and houses all government buildings, as well as other state organisations. A growing number of oil and gas companies are starting to establish headquarters in the city.

Aigoul Kenjebayeva, Dentons’ Kazakhstan managing partner, explains why it was vital that her firm established an office there: ‘We felt that we had to have a presence in Astana to help our clients on a day-to-day basis. If they have an urgent meeting with the government, rather than flying in every time we are needed at these meetings, it’s easier for us just to be based there.’

Kulzhan Mehrabi, a partner at one of the largest domestic law firms Linkage & Mind, which has offices in Almaty and Astana, agrees that having a presence in the capital is vital for her firm to be able to advise its state-owned clients more efficiently.

The legal scene

By international standards, Kazakhstan’s legal market is small and immature, with about 10,000 lawyers and 15 full-service corporate law firms, each with an average of 20-30 lawyers.

The legal profession is divided into commercial lawyers and advocates. Commercial lawyers are subject to general civil, tax and business legislation, and are able to deal with general legal issues and civil cases. However, they are not allowed to represent clients in criminal and administrative proceedings in the courts, this being the sole preserve of advocates, who are regulated by Law on Advocates.

While advocates are regulated at both regional and national level, and require a licence from the Ministry of Justice, commercial lawyers remain lightly regulated and require no licence to practise.

To remedy this lack of regulation the Kazakhstan Bar Association (KazBar) was formed in April 2012. Membership of the association is currently voluntary, but it aims to improve the quality of the country’s legal services, and establish a legal framework for regulation of the profession.

Dentons’ Kenjebayeva is a member of KazBar’s board of governors. She believes that the formation of the professional body is a necessary and positive step towards self-regulation of the legal profession. ‘The majority of the larger Kazakh law firms have joined the KazBar,’ she says. ‘There is growing understanding of the need to self-regulate, if we are to avoid regulation by the government. Without this regulation, anyone can go to the courts to carry out advocacy in a civil trial.’

Rashid Gaissin is managing partner at leading Kazakh firm Grata Law. Although less enthusiastic about the prospect of further regulation of his profession, he agrees that the country’s liberal stance on regulation is unlikely to continue beyond the next five to 10 years.

Mehrabi at Linkage & Mind agrees: ‘Sooner or later there will be some measures or rules introduced regulating the Kazakh legal market, possibly a membership of the KazBar, or some other such association, as well as qualifying exams and practising certificates’.

For now, legal training consists of graduates starting as legal assistants and paralegals until they gain sufficient experience to become lawyers – normally one to two years.

For foreign law firms this lack of regulation ‘essentially means that any can set up a 100% subsidiary or branch in Kazakhstan and start providing legal services to their clients without any red tape’, Mehrabi explains.

They are simply treated as commercial entities, and suffer no noticeable disadvantage other than what Mehrabi describes as ‘the lack of knowledge of the local mentality, as well as of the cultural identity of Kazakh population and, obviously, the language barrier’. Most overseas law firms have overcome these obstacles by employing experienced Kazakh lawyers ‘who basically fill this language and cultural gap’, she adds.

London calling

The growing interest of UK investors in the Kazakh market, and the consequent need for Kazakh legal expertise, has led to a number of Kazakh law firms venturing into the London legal market.

Gaissin explains that Grata Law’s London team acts mainly as a ‘representative office’, which works on marketing and business development activities, as well as building relationships with UK law firms. Half of the firm’s business comes through referral work from UK and US law firms, and the remaining 50% from predominantly gas and mining work, as well as, to a lesser degree, construction and infrastructure work. Unusually for a Kazhak firm, Grata Law employs around 100 lawyers, and has offices throughout central Asia, as well as in London and New York.

Gaissin is also vice-chairman of The British-Kazakh Law Association (BrKLA), which was relaunched in 2010 and aims to foster greater corporation between British and Kazakh lawyers.

The Law Society has been highly supportive of the BrKLA and sent delegates to Kazakhstan in 2011 to attend one of its events and to meet with local law firms, as well as sending representatives on a 2012 trade mission to the country.

Linkage & Mind is another Kazakh law firm looking to set up an office in London. Mehrabi explains that although her firm is still in the process of looking for office space, the firm has already started its legal activities there, frequently acting in partnership with UK law firms such as Speechly Bircham and Eversheds. She adds that while many investors in Kazakhstan still demand that their contracts are governed by English law, Kazakh expertise is required on other aspects of a transaction, such as tax, and import and export duties. Three-quarters of Linkage & Mind’s client base comprises foreign investors. The firm has ambitious plans for its London office, and in addition to acting in partnership with local firms, is looking to develop its own client base.

Sayat Zholshy & Partners also has a representative office in London, led by Alexey Yanchenko.

Jurisdictional issues

Although Kazakh legislation is developing rapidly, as yet it does not recognise some key legal concepts which are vital to international finance, and mergers and acquisition deals. As a consequence, and with parties to a commercial agreement able to choose the jurisdiction that is to apply to their agreements, overseas investors remain reticent about using Kazakh law as the governing law in agreements.

Mehrabi explains that without any of the bilateral treaties which would allow a western European or north American judgment to be enforceable in Kazakhstan, when things go wrong and litigation ensues, the commercial and legal risks are significant.

She adds that although she is under a duty to advise her clients of this lack of enforceability of a foreign judgment, most remain unconvinced about using Kazakh law as the governing law in their contracts.

Mehrabi notes that even if her clients were to use Kazakh law, ‘challenges’ would nonetheless remain in a potential dispute; not least the ‘uncertainty of the Kazakh judicial system’, as well as the limitations put on the amount of damages and legal costs that can be awarded by a Kazakh court. She points to a number of other facts making Kazakh law an unattractive option, including the lack of commercial experience of local judges, and judgments by a Kazakh court ‘carrying much less weight internationally than an English court judgment’.

At Grata Law, Gaissin is not convinced that this lack of enforceability is an insurmountable obstacle for overseas investors. He believes that viable alternatives exist to settle disputes, and that arbitration in particular ‘is the way forward’ in Kazakhstan, now that the country is a party to the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards.

The country has been developing a system of arbitration tribunals and intermediate courts which are outside the system of state courts. Any citizen can refer a dispute to an intermediate court, provided an agreement for intermediate settlement exists between the parties. Similarly, if there is an arbitration agreement between the parties, a dispute can be referred to arbitration, provided one of the parties to the dispute is not a resident of Kazakhstan. In theory an arbitral award is required to be enforced by a Kazakhstan court, although not everyone is convinced this is happening in practice.

Such is the interest in Kazakhstan, however, that legal uncertainties have done little more than dent its commercial attraction. In November 2012, Astana was chosen to host Expo 2017, which will take the theme of ‘future energy’. More than 100 countries are expected to participate in the exhibition, which is being held in a former Eastern Bloc country for the first time.

Dentons was appointed as chosen counsel at the exhibition. Kenjebayeva explains that it represents a great opportunity to further enhance the country’s still relatively underdeveloped infrastructure.

The winning design for the site of the exhibition was chosen at the end of October; 25 hectares is being allotted to the exhibition centre alone. Construction is due to begin early in 2014.

Dentons recently moved its real estate partner to Astana in expectation of the amount of construction and infrastructure work that the exhibition alone will generate. Others will no doubt follow.

Gaissin at Grata Law is similarly optimistic that the Kazakh market, with its relatively low inflation, will continue to hold many attractions for both overseas investors and their lawyers, and that ‘now is the time to move’ into this fast-growing country.

Corruption and human rights

Although David Cameron’s visit to Kazakhstan in the summer was primarily to drum up trade, he also addressed the issue of corruption.

The country’s relative political stability, personified by president Nursultan Nazarbayev being in power since 1991, is proving attractive to overseas investors. But his critics have accused Nazarbayev of being a dictator.

In an open letter to the prime minister, Human Rights Watch UK stated that it was ‘very concerned about the serious and deteriorating human rights situation in recent years, including credible allegations of torture, the imprisonment of government critics, tight controls over the media and freedom of expression and association, limits on religious freedom, and continuing violations of workers’ rights’. Of particular concern was an incident in December 2011 in which the police and special forces shot and killed 15 striking oil workers, and wounded more than 100, in the south-west of Kazakhstan.

Former prime minister Tony Blair’s work in Kazakhstan has also generated controversy. Tony Blair Associates has been advising the government on what it calls a ‘two-year contract’ of ‘social, political and economic reform’. Human rights groups such as Amnesty International, however, remain unimpressed at his company’s involvement in a country with such a poor human rights record, with some critics accusing Blair of orchestrating Cameron’s visit to the country.

Kazakh lawyers, as well as government officials, acknowledge that corruption is a problem. A 2011 report issued by the OECD Anti-Corruption Network for Eastern Europe and Central Asia concluded that ‘the level of corruption remains high, especially in the spending of public funds’.

In response to growing criticism, the government has made the fight against corruption a top priority, ratifying the UN Convention Against Corruption. The country has also adopted an anti-corruption strategy for 2011-2015; and the Agency on Fighting Economic and Corruption Crimes (Financial Police) is charged with coordinating this.

Dentons’ Kenjebayeva confirms that corruption remains a big problem, although ‘some good things are being done’. She credits the extra-territorial UK Bribery Act for bringing about changes for the better in how business is conducted.

Maria Shahid is a freelance journalist

No comments yet