Lawyers are cautiously optimistic about the long-term prospects of Thailand’s legal sector, despite operating amid political turmoil.

Strategically placed in the middle of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), Thailand is the region’s second-largest economy after Indonesia and has enjoyed robust economic growth over the past two decades. Yet this positive economic story is under threat from a political crisis that, despite elections in February, shows no signs of abating.

The government has cut its growth forecast for the country’s GDP, which expanded just 0.6% in the last quarter of 2013, and 2.9% in the full year.

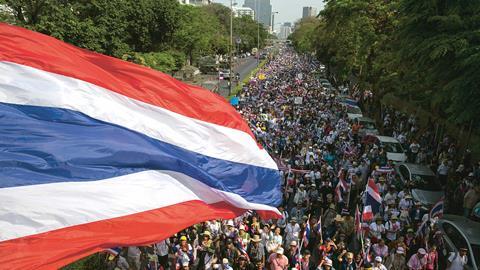

Anti-government demonstrations which began at the end of November have caused significant disruption in and around Bangkok, and elsewhere in Thailand, prompting the Thai government to declare a 60-day state of emergency on 21 January. Even after elections on 2 February, demonstrations against the regime of prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra continue, and have sparked violent clashes between the protesters and the police.

Yet most international lawyers based in Bangkok remain sanguine about prospects in Thailand, the largest exporter of rice and a major global source of car, electronics and electrical appliance goods.

Steven Burkill, managing partner of Watson, Farley & Williams in Bangkok, has been in the Thai capital since 2001. He points out that the country has faced other significant critical points, including a military coup in 2006, major protests in Bangkok in 2010 and devastating floods in 2011. Despite this, the country’s economy bounced back; in 2012 GDP rose 6.4%.

‘Thailand is very resilient and through those events our practice here has not shrunk, it has grown,’ Burkill says. Burkill describes the firm’s current financial year, ending 30 April, as ‘the best we have ever had’.

A land of opportunity

Many international law firms have set up offices in Bangkok, in part because it is time-consuming and bureaucratic to obtain business visas to service clients on a fly-in/fly-out basis.

There are some restrictions to foreign lawyers operating in Thailand, but the legal sector is relatively open to international law firms compared with other south-east Asian countries such as Malaysia or Singapore. Under the Foreign Business Act, foreign law firms can only be established as joint ventures and must register as limited companies.

The act restricts the ownership of foreign-owned law firms in Thailand to 49%, requiring Thai shareholders to own more than 50%. Only Thai-licensed lawyers, who must be Thai nationals, can advise on Thai law and represent clients in Thai courts. Foreign lawyers are restricted to an advisory role in relation to non-Thai matters.

Many international law firms entered the market in the late 1990s and have been rapidly expanding, and some boast sizeable operations today.

Baker & McKenzie was one of the first international law firms to set up shop in Bangkok, in 1977. It does a mix of local and cross-border work, employing 168 fee-earners, including 44 partners.

Reflecting a wider industry trend, over the past 12-18 months, Baker & McKenzie has been particularly busy with M&A work, both domestic and inbound, and related acquisition finance, according to managing partner Thinawat Bukhamana.

In the inbound M&A market, Baker & McKenzie was involved in one of last year’s highest-profile transactions. Together with lawyers from Allen & Overy and Sullivan & Cromwell, the firm acted on the Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ’s $5.75bn bid to acquire a controlling stake in Thailand’s Bank of Ayudhya from GE Capital.

Baker & McKenzie’s outbound activity has also increased – a sign of the current strength of Thailand’s corporations. Last year Baker & McKenzie represented CP ALL, Thailand’s largest convenience store chain and the world’s third-largest operator of 7-Eleven stores, in the purchase of cash-and-carry retailer Siam Makro from Dutch SHV Holdings, in a deal worth $6.6bn.

Bangkok-listed CP ALL is part of Thailand’s Charoen Pokphand Group (CP Group), run by billionaire Dhanin Chearavanont. Baker & McKenzie advised on the acquisition and financing aspects of the transaction.

Bukhamana says the firm’s clients – including large Thai banks and corporations such as state-owned oil and gas company PTT, agribusiness conglomerate CP Group, Siam Commercial Bank and Krungthai Bank – are expanding elsewhere in south-east Asia, as well as in Africa, Canada, China, Europe and Russia.

Other international law firms observe the same trends. ‘The bigger Thai companies are essentially “maxed out” in Thailand, and they need to go elsewhere to continue to expand,’ says Simon Makinson, managing partner of Allen & Overy in Bangkok. He points to a significant expansion of outbound corporate work at the firm in the past six years.

Most recently, Allen & Overy advised Bangkok-based Indorama Ventures, the world’s largest producer of polyester, on the acquisition of 80% of PHP Fibers Group, which has operations in Europe, the US and China.

Law firms are also deriving business from the country’s rapidly expanding telecommunications sector. Makinson notes that, as in many other parts of the world, Thailand’s telecommunications industry is heavily regulated, and this has given rise to ‘a highly contentious regulatory environment’.

Allen & Overy’s litigation team regularly advises telecom companies on various regulatory issues, including 3G, roaming, interconnection and MNP (mobile number portability) services. Clients for this area of business include incumbent private sector mobile phone operators Digital Total Access Communication, controlled by Norway’s Telenor, and Advanced Info Service.

Like other international law firms, Linklaters has been advising local corporates on their outbound investments, such as CP Group on the acquisition of a stake in China’s Ping An Insurance. But the firm has also been very busy with high-profile capital markets work, says managing partner Wilailuk Okanurak.

For example, in the first half of 2013, Linklaters advised UBS, Morgan Stanley and Thai bank Phatra Securities on the $2.1bn IPO on the Thai bourse of an ‘infrastructure fund’ controlled by BTS Group. BTS, which operates Bangkok’s SkyTrain urban rail system, plans to use the proceeds to expand its mass transit rail network in the capital and beyond.

Linklaters advised Credit Suisse, UBS and Standard Chartered Bank, among other banks, on a second infrastructure fund IPO, launched at the end of December 2013. That raised $1.8bn. The fund houses the infrastructure assets of True Corp, the country’s largest telecoms company, which is owned by Chearavanont.

Okanurak says infrastructure funds provide new means to raise finance for large-scale, costly projects in Thailand. This new funding instrument allows private companies or state-owned enterprises to raise capital from the public, reducing government spending.

The Thai government approved the establishment of infrastructure funds at the end of 2009, and in 2011 the Securities and Exchange Commission of Thailand set the criteria, conditions and procedures for the formation and management of the funds, including the types of projects infrastructure funds can invest in. For example, infrastructure funds can invest in water, telecoms and electricity projects.

Last year, the Thai government announced a seven-year infrastructure development programme worth 2.2tn Thai Baht (£40.6bn). Finance will be raised through a variety of means, including infrastructure funds, public-private partnerships – a new PPP law was passed last year – and bonds.

If Thailand’s transport system needs upgrading, so does power generation. Electricity shortages are frequent. The Thai government is providing big incentives for renewable projects, including solar, to provide power and reduce reliance on fossil fuels. The government expects renewable energy to account for 25% of the country’s energy demand by 2021 – a threefold increase from today.

As Burkill puts it: ‘The demand for energy is huge in Thailand and the desire for a significant proportion of that to be renewable energy is a matter of government policy. So the regulations in this area are very much incentivising companies to come in and develop renewable energy businesses.’

With Europe reversing its previous support for renewables, a growing number of European investors are turning to Asia in search of new markets. The firm’s Bangkok renewable energy practice has been expanding fast, Burkill notes, both on the contentious and non-contentious side. The firm has, for example, advised local and international investors on Thai regulatory issues and contractual supply arrangements in relation to solar and wind energy projects.

Norton Rose Fulbright is also winning more work in this area. ‘We have been very active in renewable energy for the past two years,’ says the firm’s Bangkok office managing partner, Somboon Kitiyansub. NRF recently advised The Siam Commercial Bank on its financing of 10 solar PV projects with an aggregate capacity of 72MW. The projects are owned by Soleq Pte Ltd and Soleq Solar (Thailand) Co Ltd, which are the investment vehicles of Singapore-based Equis Funds Group.

International law firms are benefiting from activity in the insurance and reinsurance sectors too. DLA Piper, which has been in Bangkok since 2004 and now has a headcount of 85, including 45 fee-earners, acts for major international insurance companies with a base in Thailand, including Ace, Allianz, IAG and QBE Insurance.

Peter Shelford, country managing partner for Thailand, says: ‘In the last five years there have been a lot of very major insurance claims, including the floods in 2011, which resulted in $12bn worth of claims. So [insurance] has been a particularly lucrative sector to be operating in.’ Shelford focuses on litigation and arbitration, and in particular insurance, reinsurance and marine.

On the non-contentious side, DLA Piper has built a strong reputation in real estate. One of the firm’s clients is Tesco, which in Thailand operates as Tesco Lotus, generating more than £3bn in annual revenues. In addition to the supermarket chains, Tesco Lotus develops and owns shopping centres in Thailand.

A rapidly expanding economy, and the growing weight of foreign investment, have led to a growing demand for international arbitration – provided clients can get through the hurdle of the Thai courts.

Herbert Smith Freehills’ Bangkok office, established 15 years ago, only does dispute resolution work, including arbitration and cross-border litigation. For example, HSF is acting as Thai counsel in the defence of a large Thai insurance brokerage company in court proceedings brought against it in Toronto, Canada. The case, worth more than CAD$3.5m, centres on issues arising out of the flooding in Thailand in 2011.

Partner Chinnawat Thongpakdee observes that ‘levels of international arbitrations have dropped a bit’ over the past three to five years, partly because of a decision by the Thai cabinet in July 2009 to forbid, on principle, any contract entered into by the government and a private entity, Thai or foreign, from containing an arbitration clause as a method of dispute resolution.

This follows a Cabinet resolution in 2004 that required any disputes relating to concession agreements to be submitted to the country’s administrative courts. The inclusion of an arbitration clause in any contract with the government, including any state entities, is now subject to cabinet approval on a case-by-case basis.

The bargaining power of the party contracting with the government – for example, a large foreign multinational – is an important factor, Thongpakdee adds. The ban is nevertheless significant in a country where state-owned enterprises (SOEs) play a significant role in Thailand’s infrastructure development.

Thongpakdee notes that the history of these new rules dates back to 2003, when a Thai civil court upheld a 6.2bn Baht (£114m) arbitral award against the Thai government in a highly publicised arbitration dispute between privately owned Bangkok Expressway Plc and Expressway and Rapid Transit Authority of Thailand, a SOE, over the construction of a 55km expressway. It is understood the Thai government sought to avoid these high-level awards multiplying.

Baker & McKenzie’s experience in dispute resolution is to a large extent dealing with contentious matters through the country’s two-tier administrative courts, which have jurisdiction over disputes between the private sector and the state. ‘We represent a lot of big corporations in Thailand and most of them have deals with the government,’ says Bukhamana. ‘Most of the time they have disputes with the government, and our litigation practice group represents them in suing the government in the administrative courts.’

In the last five years there have been a lot of very major insurance claims

Peter Shelford, DLA Piper

Notwithstanding the restrictions introduced over the last decade, international arbitration has been picking up fast for Watson Farley & Williams (WFW), and currently accounts for about 70% of its fee income in Thailand. As Burkill puts it: ‘International arbitration is on the increase, without question.’ WFW, which focuses on shipping and energy, is conducting international arbitration proceedings in London on behalf of subsidiaries of state-owned oil and gas company PTT.

In addition to London, other popular venues for WFW’s Thai-related work are Singapore (SIAC), Hong Kong (HKIAC), and China (CIETAC). Arbitrations at the Thai Arbitration Institute (TAI) are less in demand, partly owing to the ‘tight control on costs of arbitrators’ which, Burkill says, reflects on quality.

Burkill adds that Thai clients – whether in contractual agreements with international or national counterparties – ‘are content to sign up to an arbitration dispute resolution agreement, because what they see is speed, cost recoverability and enforceability’. This is because in Thai courts successful claimants will only receive nominal costs awards and also because there’s been a ‘sea change’ in enforcement in the local courts.

‘The practice of enforcing used to be hit and miss, but in our experience in the last five years the Thai courts have become much better at enforcing foreign arbitral awards, and understanding that there is limited scope for challenging [them],’ says Burkill.

Obstacles in the way

So what are the main challenges facing international law firms operating in the country? Bribery and corruption is a significant risk for anyone doing business in Thailand, including lawyers. Thailand slipped from 88th place in 2012 to 102nd place in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index 2013, of 177 countries. This is better than neighbouring Indonesia (114) and Vietnam (116) but well behind Singapore (5).

Perceived corruption in the judiciary, for example, appears to be a risk for clients. One senior international lawyer, who did not wish to be identified, says another reason international clients prefer to resolve their disputes in international arbitration courts is because ‘you cannot guarantee that Thai courts are clean’, although he adds: ‘The higher up you get the cleaner it gets.’

Furthermore, there is the issue of language. Court proceedings are conducted in the Thai language and this requires that all documents be translated and that witnesses give evidence in the language.

In addition, as Makinson notes, Thailand’s legal system, which follows the civil law tradition, poses additional challenges to international lawyers that do not exist in London, New York, Hong Kong or Singapore, where big financial centres co-exist with a common law system.

‘The Thai civil law was developed in the 1920s when Thailand was primarily an agricultural economy and has not changed much since. Therefore structuring transactions, as you would in a country with a more flexible, commercially adaptable common law system, is more difficult,’ Makinson says.

In Thailand most legal matters involve Thai law, notes Thongpakdee. ‘Foreign firms need to have the right mixture of international and Thai law expertise,’ he says.

The upshot is that Thai-licensed lawyers account for the majority of fee-earners at international law firms established in Thailand. For example, 90% of DLA Piper’s fee-earners are Thai-qualified, while all fee-earners bar one at Linklaters are Thai-licensed lawyers. At Baker & McKenzie, 30 of the firm’s 44 Bangkok-based partners are locally qualified lawyers.

Although lawyers to whom the Gazette spoke said the quality of local lawyers has improved ‘quite substantially’ over the past 20 years, there remains a shortage of local talent in senior positions. If the Thai legal market has its fair share of challenges, overcrowding does not seem to be one of them. Kitiyansub notes that there have been very few newcomers into the market in recent years and today there is no big pressure on pricing.

‘Clients have become more sophisticated and they are focusing more on the quality of the work rather than price,’ he says.

Political uncertainty remains the biggest short-term risk. Shelford told the Gazette that just before the elections on 2 February he was forced to evacuate his flat because of the protests. ‘It’s a very challenging scenario at the moment, and certainly it’s going to have an impact on foreign investment in Thailand,’ he says. The bulk of DLA Piper’s work in Thailand – both contentious and non-contentious – is for Thai subsidiaries of foreign entities.

Shelford, who relocated to Bangkok from Singapore in 2006, notes that the firm did not suffer following the last big Bangkok protests in 2010, when more than 90 people died after the army opened fire.

For his part, Bukhamana expresses the hope that the domestic political turmoil will be over by the end of the first quarter. If not, there is a risk that locally sourced work will be affected too. Baker & McKenzie’s output from inbound transactions fell by about a third in the two-month period between the start of the political unrest in November 2013 and the end of January.

Some lawyers add that companies will probably hold off on any public share sales until the political situation stabilises.

Makinson says the ongoing anti-government protests have disrupted some client meetings, but not much else. Despite the short-term risks, he notes that Thailand’s medium-term prospects remain strong, pointing to its sound macroeconomic fundamentals, including near-zero unemployment, low inflation and solvent banks.

But he adds: ‘Stability of political institutions is something that clients will have on their risk assessment and, at the moment, they wouldn’t be ticking the box indicating [the country] is completely stable.’ He adds: ‘They’d be saying that, based on past history, there have been upsets but things have always worked out – although at the moment they would be saying that with less certainty than before.’

Cautious optimism appears to prevail in Bangkok for now. But whether political troubles derail what has been a real success story for clients and firms alike remains to be seen.

Marialuisa Taddia is a freelance journalist

No comments yet