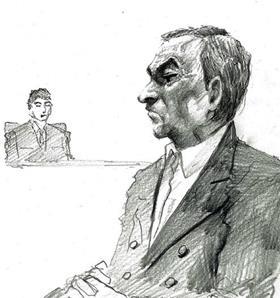

Today’s Japanese news media are dominated by artists’ impressions of a gaunt 64-year-old businessman standing in the dock of the Tokyo District Court. Carlos Ghosn, former chairman of car giant Nissan and currently chief executive of Renault, had chosen to appear before the first-instance court to deny in public a charge of submitting financial accounts understating his salary.

The appearance attracted extraordinary interest in a country where courtroom dramas are unusual: news reports said that 1,100 people queued for 14 public gallery seats. Part of the interest of course stems from the high profile of the accused: despite the economic turmoil of the past 20 years, captains of industry are still heroes in Japan. But the real sensation - and this is not to make any judgment on the merits of the charges - is Ghosn's 'not guilty' plea in a criminal case.

Despite recent reforms supposed to introduce an element of trial by jury, the Japanese system in general remains wedded to the ideal of courts delivering guilty verdicts more than 99% of the time, usually on the basis of confessions extracted after lengthy police detention. (Over several years as a correspondent in Tokyo I recall reporting only one case involving a not-guilty plea; significantly that was an Australian on a drugs charge. He didn't get off.)

The expectation seems to be that Ghosn, a Brazilian-born French citizen, will play the game. He has been in custody since his initial arrest at Haneda Airport on 19 November and was led into court, handcuffed, by a rope around his waist. Journalists noted that he had lost weight in custody and, while allowed a suit and open-neck shirt, was shod in plastic slippers. The presiding judge had no truck with suggestions of bail, ruling Ghosn a flight risk. He is likely to spend at least six more months inside while investigations into allegations of aggravated breach of trust continue.

Along with many other trappings of a modern state, Japan's judicial system was essentially imported from Europe in the late nineteenth century. While the reforming government looked to Prussia for its army and Britain for its navy (setting it on course for grief in the twentieth century) it picked France's inquisitorial system as a model for justice, and one that chimed well with Confucian notions of respect for authority. It has been modified since, of course, notably under the US-imposed postwar constitution. A more recent reform has introduced lay judges sitting as quasi jurors with the professional bench on death penalty cases.

At one level, the system operates with notable efficiency. Western policymakers are often attracted by the emphasis on out-of-court settlement in civil cases. This is reflected in the tiny number of judges - fewer than 4,000 at all levels, supported by 10,000 judicial clerks who take on many procedural tasks - and the low lawyer-count per head of population, still a fraction of England and Wales', let alone that of the US. Meanwhile, anyone who has lived in Japan will remember fondly the liberating experience of simply not having to worry about petty crime. (Organised crime is another matter.)

But, as international human rights groups frequently report, efficiency has its dark side. Modern Japan may be a strong democracy subject to the rule of law and with a vigorous and increasingly pluralistic civil society, but its criminal justice system reflects more traditional values.

1 Reader's comment