Sir Brian Leveson has completed his independent review of the criminal courts and his report will be published by the Ministry of Justice in the next few days.

The former head of criminal justice was asked by the lord chancellor last December to consider ways of ‘reducing demand on the Crown court by retaining more cases in the lower courts’.

That must mean reducing the proportion of cases that are tried by juries. But in case he was in any doubt, Shabana Mahmood told Leveson he could consider the ‘reclassification of offences from triable either-way to summary-only’ and structural changes including the introduction of an intermediate court.

We can be confident that Leveson has been faithful to his terms of reference. Battle lines are already being drawn, with lawyers setting out to defend jury trial and the courts minister insisting that justice delayed is justice denied.

If nothing is done, says Sarah Sackman, the backlog will hit 100,000 before 2028. Figures published a week ago show that the number of outstanding cases in the Crown court reached 76,957 in March, an increase of 11% on the previous year.

As I have found to my cost when writing about trial by jury, many people are utterly devoted to it. Because the version of Magna Carta that remains in force says ‘No freeman… shall be imprisoned… but by lawful judgment of his peers’ – or perhaps because Tony Hancock famously asked his fellow jurors ‘Did she die in vain?’ – some people imagine that jury trial in its present form goes back to 1215.

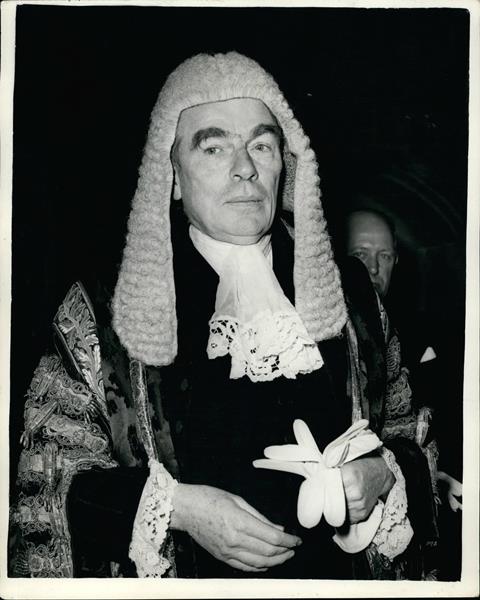

Far from it. In the Hamlyn lectures he gave in 1956, Sir Patrick (later Lord) Devlin (pictured below) explained how the jury changed its character over the centuries from a body of witnesses to a panel of adjudicators. ‘It was not until the 16th century,’ he said, ‘that the jury had to be considered as a body of reasonable men exercising a rational function.’

And of course, it has changed hugely since then. When Devlin was speaking, most jurors were male property owners under 60. Those called to serve could be removed by peremptory challenge but their verdicts – usually delivered after no more than five hours’ deliberation – had to be unanimous.

Read more by Rozenberg

Juries used to decide civil claims in England and Wales, though Devlin said these had ‘diminished enormously’ over the first half of the 20th century. There was still a right to jury trial in defamation cases; but that was effectively abolished, without evident complaint, in 2014.

For some, the advantage of a jury trial is its protection against an over-mighty state. When I interviewed Devlin to mark his 80th birthday in 1985, we discussed the case of Clive Ponting, a civil servant who had been recently acquitted of charges under the Official Secrets Act – even though there was no doubt that Ponting, who died in 2020, had leaked secret documents about the sinking of the Argentine cruiser General Belgrano during the Falklands war.

Devlin told me a jury had a right to be perverse in the exercise of what he called its legal and constitutional spirit: ‘If it’s asked to enforce law which it really feels is against its conscience, it says no and it acquits. And that’s to my mind our proudest constitutional achievement.’

But judges can also rein in the state’s excesses. In April 2024, Mr Justice Saini refused to grant one of the Conservative government’s law officers permission to bring contempt of court proceedings against a woman who had merely held up a sign at the entrance to Inner London Crown Court. The solicitor general had argued that Trudi Warner’s placard was intended to encourage jurors to perform their role in a particular way.

Of course, nobody is suggesting that jury trials should be abolished. It will remain mandatory for the most serious cases – perhaps with the exception of very long fraud trials. But the question for Leveson, and ultimately for parliament, is how serious a case has to be before a defendant can demand trial by jury.

Take the offence of common assault, which carries a maximum penalty of six months’ imprisonment. Nobody would suggest it should be tried by a jury. But the defendant can choose a jury trial if the assault is said to have been racially or religiously aggravated – or if the victim is an emergency worker. Although the maximum would then be two years, any prison sentence is likely to be well within the 12 months that the magistrates can pass. Why, then, should the defendant be entitled to a jury trial?

Once we accept that criminal charges can be tried fairly by a bench of lay magistrates or a district judge, the only question is which either-way cases should be reclassified as summary-only. When we know what Leveson recommends, parliament will have to make up its mind.

5 Readers' comments