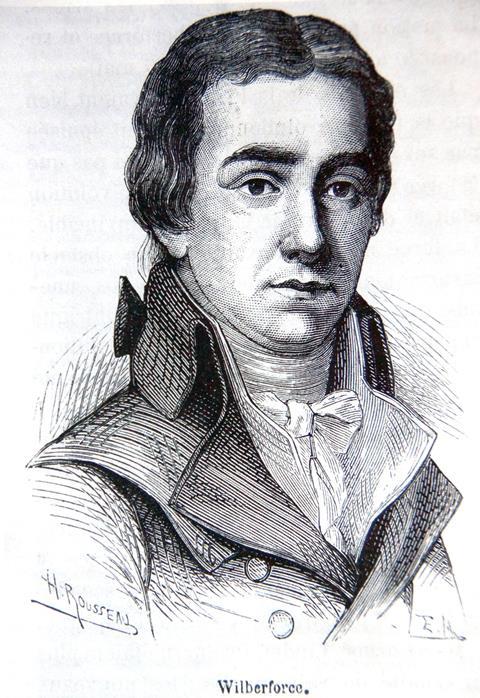

One of the proudest moments of leadership and transformation in British history was the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade. As the BBC recently spotlighted in its annual Reith Lectures on 'Moral Revolution', in the 19th century figures like William Wilberforce spent decades in parliament fighting to pass anti-slavery motions and set a moral standard. Yet today, when it comes to standing against horrific instances of modern-day slavery, the UK is falling behind.

While the use of forced labour continues to infiltrate the supply chains of textiles, electronics, and many more, efforts by the UK to prevent contaminated products from reaching consumers is falling behind other nations. If the Labour government wants to remain a credible champion of human rights and the rule of law, it needs to act with urgency to address this issue.

The scourge of forced labour is most stark in the Uyghur region (Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR)) of China, where the Chinese government subjects Uyghurs and other predominantly Muslim minorities to mass detention, coercive labour transfer schemes, and widespread abuses that amount to crimes against humanity. China also operates state-led labour transfer programs which relocate workers to factories outside of the region, making it critical for countries receiving goods from China to have strong enforcement measures to detect where forced labour is being used.

Last year, our team at Global Rights Compliance, released an investigative report showing that many critical minerals supply chains, and consumer products using these minerals, are tainted with Uyghur forced labour. These goods are entering global supply chains and being sold by leading brands en masse. Critically, the report identified that exports from the Uyghur Region to the UK increased by 595.2% in 2024. This statistic adds to a growing body of evidence establishing the UK as a potential ‘dumping ground’ for goods made with state-imposed forced labour.

This finding was echoed last summer, when parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights report warned that the UK is ill-equipped to prevent goods made with forced labour from entering the domestic market. The Committee concluded it is almost inevitable that such goods are already in homes across the UK. This rising exposure is due in part to the proliferation of new direct air freight routes from the Uyghur Region to UK airports, aiding the dumping of millions of pounds worth of tainted goods into the UK market each year. The air carriers responsible for the transportation of products linked to these egregious rights violations cited technical compliance with existing UK anti-slavery laws as a shield against accountability.

Britain’s current safeguards, centre largely on the Modern Slavery Act’s corporate self-reporting requirements. Placing the burden on companies to self-police while offering little consequence when they fail, has however proved an ineffective regime. As a result, UK consumers cannot be confident that their purchases are free from exploitation, and ethical business models are not incentivised.

It is clear that we are falling behind our American and European partners. The United States has enacted the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA), which prevents the importation to the US of goods mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part in the XUAR. The law accurately recognises that coercion is so pervasive in the region that assurances alone are insufficient. The EU has passed a comprehensive Forced Labour Regulation (FLR), which applies to all products, regardless of origin, targeting forced labour globally, not just specific regions like the UFLPA.

Both of these laws are far from perfect or universally effective, yet they represent serious attempts to close loopholes that allow companies to profit from exploitation. By contrast, the UK is relying on outdated frameworks ill-suited to match the scale and complexity of modern supply chains.

Fortunately, momentum for reform is building. In December, the Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner urged the government to adopt binding due diligence laws and introduce a ban on forced-labour goods, complete with a rebuttable presumption that shifts the burden of proof to importers in contexts of state-imposed forced labour. While aspects of the proposal deserve debate and improvement, the demand for change is getting louder.

Appetite for reform is also growing within parliament. Last year, the UK government passed an amendment to the GB Energy Act which tackles the clean energy sector’s widespread dependence on minerals produced with state-imposed forced labour. This new measure will enable GB Energy to ensure its supply chains are not exposed to forced labour practices, thereby protecting the UK’s transition to renewable energy from complicity in widespread rights violations.

Although this is a promising step, it is the government’s responsibility to fully disengage from any points of exposure to Uyghur forced labour in its own supply chains, and to hold companies in the UK to account. Honoring and embodying the legacy of the anti-slavery movement, the United Kingdom can and should ensure that we have stronger forced labor laws to protect workers, consumers, and businesses alike.

Our leaders must choose whether they will lead once again in defeating slavery, exploitation and injustice, or accept our country becoming a weak link in this global struggle.

Lara Strangways is the senior legal adviser and business & human rights division lead at Global Rights Compliance

No comments yet