Mental illness remains a taboo subject in many workplaces. But some legal employers are trying to break the stigma, reports Jonathan Rayner.

Complaining about a mental health problem is tantamount to malingering: that remains the belief in some parts of the profession.

The remedy, those same circles maintain, is to pull yourself together, get to the office earlier and leave later. That will fix any issues you may have about an excessive caseload and the longer hours will ensure you sleep better.

Unsurprisingly, such ‘tough love’ does more harm than good. When the perceived remedy is to ‘man up’ and stop whinging, then it becomes a sign of weakness to confess concerns about one’s state of mind to a colleague. And so our culture sweeps the problem under the carpet, and people with mental illness are left unrecognised and untreated.

One in four UK adults will experience a mental health issue at some point. Sufferers can be left to suffer alone. Their relationships with their families are harmed. Their work deteriorates, becoming peppered with mistakes that they would never have made before. Eventually, some turn to alcohol, drugs and even suicide.

While poor mental health can be a downward spiral, it does not have to be. Law firms, charities and the Lord Mayor of London are stepping in to help.

Spotting the signs

London firm Farrer & Co has invested in ensuring that no colleague who is having such an experience suffers without support. Human resources director Suzanne Hulls is one of 12 at the firm to have recently completed a mental health first aid (MHFA) course, developed by MHFA England.

‘Of course, the training didn’t teach us how to diagnose medical conditions,’ Hulls says. ‘It just showed us how to spot the signs that something is wrong. Our role is to signpost the sufferer towards medical help – towards a trained and qualified doctor.’

Trainees are taught to ‘listen’, says Hulls, rather than ‘rush to a judgement that might affect someone’s life and career’.

She described a role-playing exercise that was particularly effective: ‘There were three people in a group: two of them having a conversation while the third whispered in their ears. Hearing voices in your head is a symptom of schizophrenia. We learned how devastatingly confusing and unsettling that feels.’

Hulls’s ‘master plan’ is to have a MHFA-trained person in every department in her firm.

‘The ideal candidate is someone who is approachable,’ she says. ‘Not necessarily a manager, although it helps if senior people support an initiative.’

Private client team partner Bryony Cove is one such person. Prior to the course, she had developed an interest in mental health through advising people on issues of capacity.

‘Where the course has made a real difference,’ says Cove, ‘is helping us differentiate between the various ailments.’

A central tenet of MHFA is that by talking about mental health, the stigma is reduced. But Cove says that a first-aider must not become ‘an evangelical preacher’ on the subject. At the same time, ‘we must also give people the right to be private about their condition’.

Adam Carvalho, a senior associate in Farrer & Co’s contentious trusts and estates team, also attended the MHFA course. He suggests Farrer is ahead of the curve when it comes to addressing the stigma around mental health. ‘The firm has a more open culture around mental health problems than other firms I know of,’ he says. ‘We already have half-day conferences when four non-partner lawyers get together to talk and iron out issues. Lots of us go through periods when we suffer from stress or depression. We struggle to get things done and worry we might get it wrong. These informal conferences are a positive step in the direction of destigmatising the problem.

‘We have all known people who are going through difficult times, but Farrer & Co people like one another. Talking about your own experiences humanises the whole subject.’

Kayleigh Leonie, Law Society Council member and employment associate at international firm Trowers & Hamlin, has helped create guidance for employers on how they can support staff who have mental health problems.

She tells the Gazette that the guidance, produced on behalf of the Law Society’s Junior Lawyers Division (JLD), arises from a 2017 resilience and wellbeing survey of the JLD membership. The survey found that some 90% of respondents had experienced stress of varying severity in their jobs. Yet 73% of respondents either did not know whether their employer provided any help, guidance and support, or thought that their employer did not.

The same proportion of respondents believed that their employer could do more to alleviate the effects of stress at work.

This is not ‘generation snowflake’ wanting attention. Mental ill health has a damaging impact on the British economy. According to Deloitte, which provided support for a review into mental health in the workplace commissioned by Theresa May in January 2017, mental ill health costs the UK economy between £33bn and £42bn per year: around 2% of the UK’s gross domestic product.

This cost is borne by businesses of all sizes and across all industries, so there is clearly a business case for reducing mental illness problems at work.

Leonie stresses: ‘Our guidance urges firms to appoint MHFA-trained personnel to listen to and direct those suffering from stress towards appropriate support. My own firm, Trowers & Hamlin, already has wellbeing mentors across all its offices. A number of colleagues have also completed the MHFA training.’

The Society’s guidance mirrors Trowers & Hamlin’s initiatives, calling for a culture change where mental ill health is no longer a taboo subj ect. According to the guidance, this can be brought about by appointing wellbeing mentors who will encourage people to be more open about mental health problems they may experience, and encouraging sports and social activities to help overall wellbeing.

But can smaller firms afford the luxury of such mentoring? Leonie previously told the Gazette that ‘by supporting its workforce, an organisation can significantly boost workplace morale and productivity as well as attracting and retaining talent’, (1 February 2018).

The Deloitte research endorses this, citing a 4:1 return on investment in workplace mental health interventions. But Leonie remains cautious: ‘The legal profession [still] has a long way to go to alleviate the stigma around mental health.’

Help for lawyers

LawCare is the UK’s only charity that focuses exclusively on lawyers’ mental and physical wellbeing. It offers support to everyone in the legal community, including solicitors, trainees and barristers.

Chief executive Elizabeth Rimmer says: ‘The law has an unforgiving culture of long working hours and of winning and losing [cases]. Billable hours put you under enormous pressure and can leave you thinking that you’re only valued for how much money you bring in. All this, plus a heavy caseload, frequently causes stress and mental health issues.

‘Where do you look for help? Lawyers are used to sorting out other people’s problems, not their own. The problem remains invisible, swept under the carpet and unresolved.’

An increasing number of lawyers are looking to LawCare. The charity’s helpline dealt with nearly 900 calls in 2017 from 616 callers, an 11% increase on the number of callers in 2016. Nearly half of the callers cited workplace stress (27%) and depression (17%) as the reason they were seeking help. Bullying and anxiety were also frequently cited.

Rimmer acknowledges that progress is being made, but says that there is still much more that firms and individuals can do to improve matters. She lists, among other measures, better work/life balance, flexible working, commitment from senior leaders, challenging the stigma, raising awareness, signposting support, MHFA training and good line management.

As Rimmer has stressed, organisations are only as strong as their people. A healthy and productive workforce, where staff feel valued and supported, will be more committed to the organisation’s goals and perform better in their jobs. ‘Mental health matters,’ she says – and there is copious evidence to prove it.

- www.lawcare.org.uk (helpline: 0800 279 6888)

- Helpline: 0800 279 6888

EXPLODING THE MYTHS

This is me

The Lord Mayor of London’s This is Me campaign encourages employees to share their mental health stories with colleagues via video message. The City-wide campaign aims to reduce the stigma of mental illness and dispel the myths around mental health in the workplace. It also aims to raise awareness of wellbeing: a mindset that allows us to realise our own potential, cope with the normal stresses of life, and work productively and fruitfully.

www.thelordmayorsappeal.org/a-healthy-city/this-is-me

City Mental Health Alliance

Chaired by Nigel Jones, an intellectual property partner at magic circle firm Linklaters, the alliance aims to support all City workers and not only lawyers. The alliance’s vision is to help people talk about mental health without fear of being stigmatised. To quote its website: ‘We wish for mental health to be recognised as a boardroom issue and considered essential to maximise business performance, critical to managing business risk and vital to safeguarding organisations’ people responsibilities. We believe that prevention should be recognised as equally as important as treatment to address mental health problems.’

MHFA England

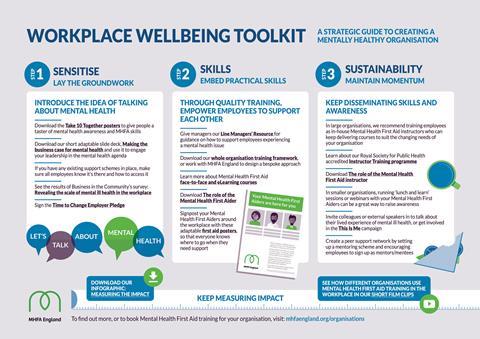

Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) England is on a mission to train one in 10 of the country’s population with the skills necessary to help people cope with and overcome mental ill health. Its website says: ‘Mental health education empowers people to care for themselves and others. By reducing stigma through understanding, we hope to break down barriers to the support that people may need to stay well, recover, or manage their symptoms – to thrive in learning, work and life.’ The organisation has trained 250,000 people in England.

No comments yet