Business is booming for international tax lawyers as multinationals and the ultra-rich look to navigate their way through a fast-changing and increasingly complicated global tax environment.

Tax lawyers for multinationals and the ultra-wealthy are enjoying a work bonanza amid a global crackdown on avoidance and evasion.

‘The rate of change in international taxation has been phenomenal,’ says Vimal Tilakapala, a tax partner and co-head of the UK tax practice at Allen & Overy.

In particular, he says, the firm is dealing with reforms commenced through the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project, initiated by the G20 in 2012 and led by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). BEPS are defined as tax avoidance strategies used by multinationals ‘to exploit gaps and mismatches in tax rules to artificially shift profits to low or no-tax locations where there is little or no economic activity’.

THE LOW DOWN

‘A huge win in the fight against tax-dodging’. That was the verdict of one campaign group last month on the government being compelled to oblige the UK’s overseas territories to make public the real owners of all their registered companies. As a coordinated, worldwide crackdown on evasion and avoidance continues, international tax lawyers gauge the growing heft of the compliance regime by the ballooning size of their reference manuals. Their practices are growing larger and more specialist as multinationals and the super-rich buy more external advice to try and make sense of their increasingly arcane tax affairs. What was once the domain of the Big Four is now their business too. And what used to be personal is now profoundly political. Tax planning is more sensitive than ever before as the public bridles at avoidance mechanisms that strain credibility and appear solely devised to minimise liabilities.

More than 100 countries and jurisdictions are collaborating to implement the OECD’s 15-point action plan of 2013. The aim is to harmonise international taxation to ensure profits are taxed where they are generated.

‘In the UK we have had new legislative codes, including those for hybrid mismatches and corporate interest restrictions, and a huge amount of new anti-avoidance legislation,’ Tilakapala says.

Lawyers measure the ever-increasing range of taxes, and their complexity, against the size of the reference manuals. ‘When I started, tax law occupied two volumes – one yellow and one orange,’ says Gibson Dunn London-based partner Nicholas Aleksander. ‘It now occupies eight or 10 volumes, depending on your choice of publisher.’

Firms’ tax departments have also grown. For example, Baker McKenzie’s London head of tax Mark Delaney has seen his department almost double in size to 12 partners and more than 50 associates in three years.

A&O’s UK practice is also expanding, says Tilakapala, partly because of increased workflow elsewhere in the firm. The tax department works closely with the capital markets, banking and corporate law teams. ‘When they are busy, we are busy,’ he says.

Meanwhile, tax advisory work has grown as companies turn to external advice to manage ever-more-complicated tax affairs.

‘One of the challenges is keeping up to date,’ says Tilakapala. Some recent legislation, such as the hybrid mismatch rules (the anti-avoidance rules introduced in April 2017 in response to Action Point 2 of the OECD’s BEPS project) are so complex that there are unresolved areas of uncertainty.

‘We are also having to rely more on tax authority guidance, which itself changes, and this is not an ideal position to be in,’ Tilakapala adds.

Pinsent Masons partner Eloise Walker says the BEPS project has led to significant changes in the UK. These include the hybrid mismatch rules, and a restriction on the amount of interest expenses that companies can deduct from profits for tax purposes, which was introduced from April 2017.

‘This was a particular concern for those operating in sectors which tend to be highly geared, such as infrastructure projects and real estate,’ Walker says. ‘The rules have impacted on cashflows for deals and caused a major administrative headache, as in many cases complex calculations have to be performed to work out whether or not the interest restriction will bite.’

In a global context, stresses Peita Menon, head of White & Case’s London tax practice, countries are repositioning their tax systems as attractive from the perspective of a headline rate. But delve deeper and this rate is often balanced by a raft of anti-avoidance rules which can exceed their originally stated remit, thereby catching both innocent and aggressive structures.

Not only do global corporates have to manage this ‘apparent contradiction’, but in reassessing their structures to make them compliant they also have to deal with any inconsistent application of BEPS in individual jurisdictions, Menon says.

Aleksander says the progressive implementation of BEPS is probably having the most significant impact on his practice. But he also points to the lack of stability in the UK tax system.

‘Each year we have a long Finance Bill, making substantial changes,’ he observes. In recent years tax lawyers have had to grapple with changes to: partnership taxation (such as the salaried member provisions); taxation of alternative investment funds that use partnerships as a fund vehicle; and the new debt cap rules. Aleksander adds: ‘And all of this proceeds amid Brexit, which will have profound implications for taxation.’

GILTI VERDICT

President Trump’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 took effect on 1 January, overhauling the US Internal Revenue Code. This includes a reduction of the corporate tax rate – from 35% to 21%; the move from a worldwide to a territorial approach to taxation of US multinationals’ foreign profits, with a one-off ‘deemed repatriation’ levy of 15.5% on accumulated offshore earnings; and a new annual levy, GILTI (global intangible low-taxed income), which imposes a minimum level of US tax on a US company’s offshore income.

The pace of change is set to continue in 2018 with the coming into force of the Multilateral Instrument, one element of the OECD BEPS project, that will affect many existing double tax treaties, Baker McKenzie’s Mark Delaney observes. ‘The European Commission also set out in March its proposals for taxing the digital economy, pending the OECD’s efforts to reach consensus on the issue,’ he notes.

Delaney cites the impact of the diverted profit tax (DPT), billed in 2015 as targeting a handful of foreign-owned multinationals which were artificially diverting tax away from the UK. In fact, this has been applied more widely and many UK groups have been affected. The tax operates on a ‘pay now, argue later’ basis. It must be paid within 30 days after receipt of a charging notice from HMRC, with no right of appeal until the expiry of a one-year review period.

‘The year gives HMRC time to review the charge but causes a serious cashflow disadvantage for the company,’ says Walker.

Into the mix practitioners also throw changes to the royalty withholding tax in 2016, and the new corporate criminal offence of failure to prevent facilitation of tax evasion, coming into force in September through the Criminal Finances Act 2017. Walker says: ‘Many risk and compliance teams are struggling to cope with the work this involves at a time when they are already stretched as a result of GDPR compliance.’

Tax planning

Complicating matters further, Tilakapala says, tax planning has become acutely sensitive. In the post-financial crisis environment, there is hostility to complex tax arrangements seemingly designed solely to minimise liabilities – for example the well-publicised Starbucks and Amazon furores.

‘We are seeing real concern in the business world to avoid planning or structuring that could be regarded as aggressive or abusive,’ says Tilakapala.

To keep up with the competition, meanwhile, firms’ tax offerings are becoming more sophisticated. For instance, White & Case’s tax practice is not reliant on deal flows which fluctuate, particularly in recessionary periods, Menon observes: ‘[It] is not a transactional, execution-only practice, but has had considerable success in developing a complementary “front office” structuring and advisory practice.’

With the Big Four accountants muscling in on legal, law firms are responding by expanding beyond the customary domains of wealth management, transactions and disputes. Baker McKenzie now provides ‘high-end’ services traditionally offered by the Big Four with ‘large standalone tax planning, transfer pricing and VAT/indirect tax practices,’ Delaney says.

Hogan Lovells’ ‘full service, economics-based transfer pricing (TP) team’, set up nearly five years ago, ‘has expanded rapidly in that time,’ says London-based partner Karen Hughes. TP reporting requirements have increased as BEPS measures are implemented across the world. ‘Our global team is also seeing more tax authority challenges where good TP advice is critical to clients,’ she says.

Disputes

‘The volume of contentious matters has increased as revenue authorities have become more litigious and more resources have been devoted to this area,’ Tilakapala says. In the UK, HMRC’s new ‘principles-based approach’ combined with ‘multiple targeted anti-avoidance rules’ have created more opportunities for the authority to challenge planning arrangements.

‘HMRC’s increasingly aggressive attitude has resulted in challenges to structuring which would previously have been seen as acceptable,’ says Walker. One example is HMRC’s use of the ‘only or main purpose’ tests to ascertain whether a transaction has a commercial or anti-avoidance purpose. ‘HMRC will argue that if the transaction is structured in a tax-efficient way at all, tax is a main purpose of the transaction, even if there is a commercial driver,’ she says.

Walker further highlights the introduction in 2014 of accelerated payment notices (APNs). APNs tackle avoidance by companies and individuals by removing their ability to defer payment of tax in ongoing disputes involving ‘marketed’ avoidance schemes (designed to exploit UK tax law and sold to taxpayers as a way of reducing their tax liabilities). Since 2014, HMRC has issued over 75,000 notices worth more than £7bn and collected nearly £4bn.

And, Walker adds, ‘we are beginning to see DPT charging notices’. In 2016/17 the amount raised from DPT notices was £138m (in addition to £143m in corporation tax from behavioural change by businesses). ‘The tax is affecting a wider range of businesses than originally expected – you do not have to be a tech company to find potential DPT exposure,’ she says.

For lawyers, the beauty of tax disputes is that they can have very long lifecycles. Years can elapse between the original transaction giving rise to a dispute and resolution.

HMRC’s approach to resolving tax disputes through civil procedures, including negotiation, is outlined in its Litigation and Settlement Strategy – first published in 2007 and since revised. This guide is ‘still working its way through the system’, Aleksander adds, while cautioning: ‘HMRC [does seem] prepared to take a greater proportion of disputes to the tribunal, and less willing to reach a resolution by agreement.’

‘In addition, we think most multinationals are increasingly having to view all tax disputes through an international lens, mainly as a result of changes to international tax norms, and increasing transparency and sharing of information between national tax authorities. An additional risk [is] that a single negative ruling in one jurisdiction could cause a chain reaction across others.’

Private client

And so to the super-rich. ‘Recent years have seen a succession of regulatory changes, including the move from information exchange on request to automatic information exchange under the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) and the CRS [Common Reporting Standard],’ says Forsters partner Carole Cook.

The standard, developed by the OECD and agreed in 2014, is a global standard for the automatic exchange of individuals’ financial account information on an annual basis. More than 100 jurisdictions have committed to implement the CRS; half of them, including the UK, started the exchange of CRS information in September last year. A further 53 are following in 2018.

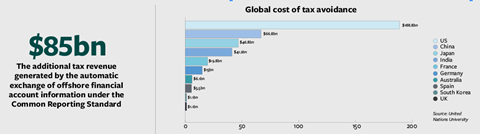

There are over 2,700 bilateral relationships across the globe for the automatic exchange of offshore financial account information under the CRS. It has already yielded more than $85bn of extra tax revenue.

The US equivalent FATCA, in force since 2013, requires foreign financial institutions and certain other non-financial foreign entities to report on the foreign assets held by their US account-holders. As Cook observes: ‘The automatic exchange of information has spawned a whole new compliance industry.’

Arabella Murphy, private wealth director at Maurice Turnor Gardner, also cites the impact of the online trust registration service launched by HMRC last July. The legal requirement for the register stems from UK’s implementation last June of the fourth EU money laundering directive. This introduced obligations for trustees of ‘taxable relevant trusts’ to provide information on beneficial owners and potential beneficiaries.

‘We have been kept occupied for years by changes to and extensions of the anti-avoidance legislation,’ Murphy says. ‘These have been prompted by successive governments on the premise that non-doms, non-UK residents, and those who use trusts are avoiding paying their “fair share” of tax.’

For instance, UK residential property held through an offshore structure such as a company or a partnership is now within the scope of inheritance tax; and under new non-dom tax rules individuals become ‘deemed’ UK-domiciled for tax purposes after 15 years out of the immediately preceding 20 tax years. ‘[That] has kept us busy with planning strategies,’ Murphy says.

The changes were introduced with the Finance (No. 2) Act 2017, backdated to take effect from April last year. This led to ‘a period of uncertainty and concern for clients’, says Payne Hicks Beach partner Frederick Bjørn. ‘Some of the rules still have to be properly interpreted by the HMRC.’

A UK public register of beneficial ownership of UK properties by overseas entities (OEBO register) is expected to go live in 2021. A draft bill is expected this summer that will introduce a criminal liability for non-compliance with the new regime. Around 85,000 properties across the UK are owned by companies incorporated in UK tax havens, research shows.

Last and most certainly not least, the government bowed to cross-party pressure for British overseas territories to make the real owners of all their registered companies public by the end of 2020. Currently such information is only available on the request of UK law enforcement agencies from four territories. Campaign group Global Witness hailed the development as a ‘huge win in the fight against tax-dodging’. The measures are part of the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018.

Legislative and political drivers on tax compliance have been good for tax lawyers recently. There appears every likelihood this will endure.

Marialuisa Taddia is a freelance journalist

No comments yet