The low down

Just as building a prestigious art gallery has the capacity to regenerate a run-down city, so building an arbitration centre is seen as a way to strengthen a legal community and the business world around it. Small wonder then that competition between rival arbitration centres seems fierce. National governments are among their powerful sponsors, from Paris’s venerable ICC to Singapore’s young and heavily subsidised SIAC. Cost, time and technology all count in this race – equality and diversity increasingly matter, too. This is also a market that could grow with the financial sector – traditionally wary of arbitration – becoming more comfortable with the process. Post-Brexit, London’s litigators hope the heft and quality of this jurisdiction will keep the cases flooding in.

The last decade has witnessed a huge shift in how frequently institutions have amended and updated their rules

Craig Tevendale, head of international arbitration, Herbert Smith Freehills

The world map of international arbitration has changed to follow the geographical contours of business. Competition has also intensified among arbitral centres and with international commercial courts. Businesses, meanwhile, are shopping around more and often choosing centres closer to home.

Three top-ranking arbitral institutions – France’s International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA), and the US-based International Centre for Dispute Resolution – featured in Queen Mary University of London’s first international arbitration survey of leading corporate counsel in 2006.

In a subsequent QMUL/White & Case study published in 2015, the list of preferred institutions had grown to five, including two centres based in Asia: the Singapore and Hong Kong international arbitration centres (SIAC and HKIAC).

Thus, international commercial arbitration has decentralised and regionalised. Stuart Dutson, international head of arbitration at Simmons & Simmons, says: ‘Clients are increasingly wanting to go to institutions in their area because there are creditable, reliable institutions that they can access now.’

In Asia, SIAC ‘is doing great business. It has come from a standing start to being one of the premier institutions in the world’, Dutson observes. Launched in 1991, in 2018 SIAC received more cases (402) than the LCIA (317), established a century earlier.

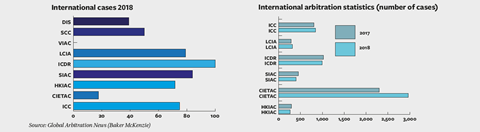

Caseload is one way of measuring the success of arbitral institutions, and on this basis ‘the fastest-growing’ has been SIAC, says Gary Born, a partner and chair of WilmerHale’s international arbitration practice group. Between 2012 and 2018, SIAC saw an increase of more than 71% in new cases, compared with growth of about 11% and 14% at the ICC and LCIA respectively, a 2019 study by Baker McKenzie’s Global Arbitration News showed.

Born also points to the latest 2018 QMUL/White & Case survey: SIAC ‘leapfrogged’ the HKIAC and became the third most preferred institution in the world (after the ICC and LCIA) and the most preferred institution outside Europe. ‘[This] is quite a feat given that it is also the youngest of the five institutions,’ he notes.

In absolute numbers, Singapore trails the ICC, which secured 869 new cases in 2019, taking the total to 25,000 since its International Court of Arbitration was founded in Paris in 1923.

Wolf von Kumberg, managing director of Global Resolution Services, casts his net wider by citing the ICDR, the international division of the American Arbitration Association, and the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC). They received 993 and 2,962 new cases respectively in 2018. The ICDR came seventh in the 2015 and 2018 QMUL rankings (CIETAC did not feature).

‘Respondents are largely from Europe,’ observes von Kumberg, the former European legal director and assistant general counsel to Northrop Grumman, and therefore ‘do not include many north American, south American or Asian respondents where the ICDR and CIETAC will be more commonly used.’

Craig Tevendale, head of Herbert Smith Freehill’s international arbitration group, observes that SIAC’s growth is ‘relatively consistent with the other older institutions’ earlier years’ and that ‘it’s also important to bear in mind that the number of cases at the institutions is intrinsically linked to the global financial outlook’. For example, there were spikes in cases in the years after the 2008 global financial crisis.

Civil unrest is bad for business

Geopolitical factors play a big role in the choice of arbitration seat. London, Paris, Singapore, Hong Kong, Geneva, New York and Stockholm were the most preferred and widely used seats (in that order), according to the 2015 and 2018 QMUL/White & Case surveys. As Wolf von Kumberg, managing director of Global Resolution Services, observes: ‘Arbitration needs a stable social and legal environment to attract participants.’

That is why the anti-government protests that have rocked Hong Kong since June ‘will definitely hurt’ it as an attractive place to arbitrate. ‘Singapore will benefit from this in the short-term and likely in the long-term,’ von Kumberg says, noting that even before the start of the civil unrest ‘Hong Kong was seen to be losing judicial independence from the mainland’.

The knock-on effects are not immediate. ‘Just because there are problems in Hong Kong at the moment, it doesn’t mean that you can suddenly change your contracts,’ says Simmons & Simmons’ Stuart Dutson. ‘But we are seeing more enquiries in relation to having clauses drafted with Singapore, where it might have previously [been] Hong Kong.’

The Singapore government is also backing other forms of ADR such as mediation, von Kumberg says, further enhancing its reputation as a dispute resolution hub. Last summer the city-state hosted the signing of the UN’s Singapore Convention on Mediation for the enforcement of cross-border mediated agreements.

For Dentons’ Paris-based partner Bart Legum, ‘a seat fares well when it supplies a rapid, predictable, less costly system for reviewing applications to annul arbitration awards. Switzerland is currently top in my view [in that] it has only a single level of review. The Swiss Federal Court is highly reliable and it decides these applications entirely on written submissions’.

It follows that ‘the best measure is how many users refer disputes to an institution in their contracts’, says Bart Legum, a partner and global co-chair of Dentons’ litigation and dispute resolution practice. But there are no statistics on this.

There are other ways of assessing the performance of arbitral institutions. London’s court, for instance, has been successful in attracting the financial industry, which was until recently reticent about arbitration. In 2018 banking and finance accounted for 29% of all arbitrations under LCIA rules, up from 24% in 2017. That stems, in part, from its focus on ‘complex’ disputes, as shown by a growing number of applications for joinder (when third parties join an arbitration in progress) and consolidation.

France’s ICC is exploring fast-emerging markets. In December, the ICC’s Task Force on Arbitration of Climate Change Related Disputes published a report on the role of arbitration and ADR in this area. It has also moved to increase global coverage with office openings around the world. ‘You can now file a request [for an ICC arbitration] in Paris, Hong Kong, New York, São Paulo, Singapore and Abu Dhabi,’ Tevendale notes.

SIAC has entered into a string of tie-ups with other international and regional arbitration centres, such as those in New York, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Beijing, as well as with CIETAC, to strengthen its ties with arbitration communities abroad.

‘Each institution is constantly seeking to expand its regional and global presence and attract users from different geographic origins,’ Born says. In 2018, the US topped the foreign-user rankings in the SIAC, surpassing India and China.

Equally, ‘the SIAC, HKIAC and SCC [the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce] strive to be real market leaders in innovation and adaptability’, Tevendale notes.

Stockholm’s SCC last year introduced a new secure digital communication and file-sharing platform to manage all its arbitrations. And under revised arbitrator’s guidelines published in October, it will reimburse arbitrators for the cost of carbon offsetting their flights to hearings.

Aside from location, the main institutions differentiate themselves by their fee structures and the degree of administration of proceedings, notes Philip Clifford QC, an international arbitration specialist at Latham & Watkins. ‘For example, while the LCIA uses capped hourly rates and lightly administers arbitrations, the ICC bases its charges upon the amount in dispute and provides for greater administration,’ he says.

‘It comes down to two main distinguishing factors: scrutiny of awards and remuneration of arbitrators,’ elaborates Born.

‘Both the SIAC and the ICC impose a greater level of award scrutiny, which I think many users of arbitration welcome. This… constitutes a review process to pick out any issue that could potentially harm the enforceability of awards,’ he says.

The ICC is especially renowned for this. Before the parties are notified of the final result, the arbitral tribunals must submit the draft awards to the ICC’s court for scrutiny and approval. The court is assisted by the international secretariat, the operational arm of the ICC comprising more than 80 lawyers and support personnel.

For New York-based Ank Santens, a partner in White & Case’s international arbitration practice, the ICC is by far the best-faring arbitral institution. ‘It is perceived as truly global and neutral, whereas all other institutions are connected to their geographical location,’ she says. It also has the ‘most extensive administrative structure with the court and an extensive secretariat; and [the] most profound scrutiny of awards’, she adds.

Institutions calculate administrative and arbitrators’ fees in two ways: ad valorem (based on the value of the claim) or capped hourly rates. The HKIAC offers both options, while most other institutions, except the LCIA, charge on the basis of the value of the dispute. Born explains this ‘allows for greater certainty and predictability in costs estimates at an early stage, which helps parties make informed decisions as to whether they should commence arbitration in the first place’.

For others there are pros and cons in both methods. Dutson says: ‘It means that you pay for the time spent, whereas with all the other institutions you pay a percentage of the amount you are claiming.’

‘The LCIA has sought to show that the hourly-rate model is cheaper in most scenarios than an ad valorem model in order to win business from the ICC,’ says Tevendale, pointing to LCIA costs and duration analysis published in October 2017.

The LCIA suggested that it had the ‘lowest’ median arbitration costs ($97,000), particularly in relation to cases with higher amounts in dispute (for example, the LCIA was less than half as expensive as the ICC for cases with amounts in dispute over $10m, it claimed).

The ICC is ‘noticeably slower’ than other institutions, Dutson observes, a downside of its scrutiny process. In 2016 the average duration of proceedings was 27 months, from the request for arbitration to the final award. The median duration of an arbitration was 16 months and 11.7 months respectively at LCIA and SIAC, according to latest available data (SIAC’s costs and duration study was published in October 2016). The ICC was due to publish similar research last year but this did not materialise, Tevendale notes.

Competition has led to a raft of procedural changes to increase the appeal of arbitration to the financial industry and other sectors. ‘The last decade has witnessed a huge shift in how frequently institutions have amended and updated their rules,’ Tevendale adds. ‘All of them now offer emergency arbitrator, expedited processes, provision for consolidation and joinder. After SIAC led the way, we’ve also seen a summary dismissal process introduced, or acknowledged as being part of the tribunal’s discretion, by these institutions over the last few years.’

SIAC was the first major commercial arbitration centre to introduce an early dismissal procedure (equivalent to the summary judgment mechanism in litigation) in its rules, in 2016. Other centres, including Hong Kong, Stockholm and the ICC, have since followed suit.

It has been a game of catch-up since 2012 when the ICC overhauled its rules with the introduction of new procedures such as emergency arbitrator, third-party joinder and case management. ‘The ICC’s rules in 2012 were very innovative and the changes introduced by SIAC in 2016, the SCC in 2017 and HKIAC in 2018 have all built on that,’ Tevendale says.

Arbitration is seen as something that can cost more and take longer than it should. That’s because parties are able to abuse the flexibility within the processes

Stuart Dutson, Simmons & Simmons

Rules are continuing to evolve. ‘On the topic of the time and cost of arbitration, a constant refrain from users, the ICC adopted [in 2017] an innovative but radical approach,’ Legum says. ‘It now overrides the parties’ arbitration agreements to impose a sole arbitrator and expedited procedures in small cases [of $2m or less].’ Fast-track procedures are available at other institutions, but they are not always automatic or are for lower-value cases.

London has resisted it longer than most, but ultimately will no doubt have similar expedited procedures introduced in its rules, Dutson says. The LCIA is expected to update its 2014 rules this year to include express powers for arbitral tribunals to order expedition and early dismissal of claims and defences.

In a globalised world, there are only a few provisions that really distinguish the institutions: for example, the ‘terms of reference’ and scrutiny of awards at the ICC, or the LCIA’s ‘annex’ on conduct for party representatives. ‘That was hugely innovative and unusual back in 2014, and it remains so in 2020,’ Tevendale observes of the London-based institution.

Arbitral centres certainly pride themselves on responding to business needs. Born, who is president of the SIAC Court of Arbitration, says this was ‘institutionalised through the establishment of the Users Council in 2015’. The council is made up of leading practitioners from jurisdictions around the world to provide feedback on draft arbitration rules. ‘The SIAC has benefited immensely from the input of the Users Council,’ Born says. ‘In addition, in the last decade, the SIAC rules went through the most number of iterations, and [it] also released its own set of arbitration rules for investment arbitration.’

The LCIA is another institution to have a Users Council, established in 2006.

But Santens observes that one common challenge facing these institutions is ‘that incremental rule changes do not really bring about a reduction in the cost and time of arbitral proceedings’.

Tevendale warns against the ‘over-judicialisation’ of arbitration as it seeks to emulate aspects of court proceedings. ‘Institutions need to be conscious to tread a careful line and not to over-legislate’ by ‘leaving enough to the discretion of parties and tribunals to tailor the right procedure.’

Arbitral institutions are stuck between a rock and a hard place, it seems. ‘Given the flexibility inherent in the major rules, how well the parties are served by the various arbitral systems depends upon the way in which their lawyers and the arbitrators conduct the cases,’ Clifford says. ‘The institutions and their rules provide the framework for the arbitral process, but the detailed implementation is necessarily left to the parties’ lawyers and arbitrators.’

Can London stay in the box seat?

As the most preferred and widely used seat of arbitration in all regions, will London lose out from Brexit?

‘Once established, something has to go very badly wrong in order to lose the branding of a safe seat,’ says Herbert Smith Freehills’ Craig Tevendale. ‘If you take into account the many thousands of ad hoc arbitrations that are seated each year in London, and which don’t appear in any one institutional statistical report, then it’s only fair to recognise that London has fared tremendously well over a sustained period.’

The UK is a signatory to the New York Convention which, as an international instrument, will be unaffected by Brexit. It also benefits from the Arbitration Act 1996, ‘a well-drafted, clear piece of modern arbitration legislation’, according to Tevendale. Furthermore, London has a ‘highly regarded judiciary, and a court system viewed as impartial’ and ‘a strong track record in terms of case law both in supporting arbitration and enforcing arbitral awards’, Tevendale says.

However, only a small majority of respondents (55%) in the respected Queen Mary University of London annual arbitration survey thought that Brexit was unlikely to affect London as a seat while 37% believed the UK capital would suffer to some extent, the survey found. In particular, it was the ‘dynamic’ between London and the second most popular seat, Paris, that might change.

According to Wolf von Kumberg, managing director of Global Resolution Services, Paris’ attraction as a safe seat has been enhanced by France’s arbitration laws, which were modernised in 2011. French judges are ‘considered pro-arbitration’, while for some parties French civil law provides greater certainty regarding damages awarded, and ‘clearly prohibits punitive damages that are common in the US’, von Kumberg says. ‘Paris is therefore becoming a more prominent European seat for arbitration, particularly for civil law cases.’

Flexibility was one of the most valuable characteristics of arbitration, the 2018 QMUL/White & Case survey found; but as many as 80% of respondents said they would also welcome rules on arbitrators’ conduct, including ‘consequences’ for delays, such as pecuniary sanctions.

‘Many users believe that arbitrators need to adopt a bolder approach to conducting the proceedings and, if need be, apply monetary sanctions for the various dilatory tactics employed by counsel,’ the survey found. ‘Due process paranoia’ was a growing concern among arbitration users; this is when tribunals are perceived not to act ‘decisively’ for fear that an arbitral award may be challenged by a party because they did not have the chance to present their case fully.

Cost was rated as arbitration’s ‘worst feature’ followed by ‘lack of effective sanctions during the arbitral process’, ‘lack of insight into arbitrators’ efficiency’ and ‘lack of speed’.

‘Of course arbitration is seen as something that can cost more and take longer than it should,’ says Dutson. ‘That’s because parties are able to abuse the flexibility within the processes, and arbitrators are not taking a strict enough line with parties. That is certainly a criticism that I hear time and time again.’

Under the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (the New York Convention) an award will not be enforced against a party who ‘was not given notice of the arbitration proceedings in sufficient time to enable him to present his case’. It means that ‘arbitrators have to be careful to give everybody the right amount of time’, Dutson says.

At the same time, arbitral tribunals must ‘feel confident enough to apply their own rules and expedite arbitrations to make them less costly and take less time. If that doesn’t happen, I can see arbitration really suffering,’ warns Dutson, pointing to the international commercial courts. ‘They don’t have the same nervousness about forcing parties to move quickly.’

In recent years, international commercial courts have sprung up in several locations, including Singapore, Qatar, Dubai, China, and Paris. This competitive pressure has not escaped institutions such as the ICC, which now penalises arbitrators, albeit for ‘unjustified’ delays only. Under guidelines introduced in 2016, arbitrators who delay submitting draft awards to the court face fee reductions of 20% or more, depending on the length of the delay.

The future of arbitration rests on some of these issues and other factors such as the application of technology to boost efficiency and diversity, according to the QMUL/White & Case research.

There has been progress on gender diversity. The ICC court achieved full gender parity (88 women and 88 men) in July 2018 when its 176 members were appointed for a three-year term.

At the LCIA, women represented 43% of all arbitrators selected by the court in 2018, but only 23% of all appointments. This highlights the role that parties play in the process, since only 6% of arbitrators selected by them were women.

In 2018, 27% of all appointments at the SCC were women. This compares with 18.4% at the ICC, although the percentage of court-appointed female arbitrators was higher (27.6%); at SIAC this was 34.3%.

On cultural and ethnic diversity, there has been much less progress. ‘While gender is getting better, the real tragic statistics are in relation to African arbitrators,’ says Dutson, who has conducted several arbitrations in Africa. ‘If you look at the number of African arbitrators who are involved in African disputes, it’s appalling. It’s in the single digits. You have disputes being resolved in relation to Africa where there is no African arbitrator on the tribunal or one out of three at most. This can’t continue.’

There is some movement on this front. Dutson, together with Stephenson Harwood’s Kamal Shah and SOAS’ Emilia Onyema, was behind the launch in September of the African Promise, an initiative (modelled on the Equal Representation in Arbitration Pledge) designed to ‘improve the profile and representation of African arbitrators especially in arbitrations connected to Africa’.

In 2018 the ICC launched an African ‘commission’ to increase inclusion and diversity on its panel of arbitrators. Currently, 13% of the ICC court’s members hail from Africa; 26% from Asia; 15% from Latin America; and 39% from Europe (with the balance split between north America and Caribbean, and Oceania).

Technology is an important factor in pursuing arbitral institutions’ quest for efficiency and some – for example, Stockholm and its SCC platform – appear outriders in this area. Technology, such as blockchain and smart contracts, will also disrupt the way disputes will be resolved and centres will need to respond. This market has a long way to develop yet.

Marialuisa Taddia is a freelance journalist

No comments yet