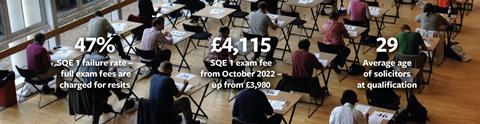

Aspiring solicitors can expect to complete an undergraduate degree £60,000 in debt, so headline salaries at City firms clearing six figures are bound to turn heads. But is this bounty being used to compensate newly qualified solicitors for a suboptimal experience of working life? Certainly, the money is not enough to hold many. And as ever, the City’s gilded – and sponsored – routes to qualification are only part of the story. The average age at qualification has risen to 29, reflecting a long and financially challenging route to qualification. The journey takes financial confidence – courage even. As inflation hits 9% and recession looms, the Solicitors Qualifying Examination’s pass rate of just 53% will add to the financial burden of many.

News stories about newly qualified (NQ) associate pay hitting record levels are flagging up the war for talent at the junior end of the legal profession. All five magic circle firms are among the City outfits offering starting salaries of around £100,000 in London, and there have been comparable increases in regional pay. Earlier this year, Eversheds Sutherland increased NQ salaries by 24% to £62,000 in the regions (and £95,000 in London). However, even magic circle firms lag behind US firms in London which are offering significantly higher remuneration. Akin Gump is leading the pack with a reported NQ salary of £164,000.

But high remuneration is balanced by the demands that transactional firms place on associates. During the pandemic’s restrictions, deal volumes remained high. This put associates under relentless pressure with less supervision and support. Furthermore, massive starting salaries do not always continue to deliver in the medium term. There are reports of ‘salary bunching’ at big international firms, meaning there are negligible differences between the remuneration of NQ associates and what they get at 1-3 years’ PQE.

Burnout and disappointing career progression are among the factors producing record levels of associate attrition (associates switching firms). According to market analytics firm Codex Edge, the associate attrition rate for firms in England and Wales increased by over a third from 10.44% in 2020 to 14.31% in 2021. Globally the figure is higher. Business intelligence company Leopard Solutions’ 2021 State of The Legal Industry Report saw associate attrition increase by almost 50% in 2021. Leopard Solutions’ Phil Flora told the Geek in Review podcast that, while money is the traditional incentive provided by law firms, post-pandemic it is just one piece of the solution.

Of course, the six-figure NQ salary is the exception rather than the norm. And NQs have to balance multiple factors in deciding how/where to qualify and work. Debt repayment is an important consideration, with the increasing cost of qualifying into the profession fuelling competition for training contracts.

‘Money is not the main driving factor’

Flex Legal’s Future Lawyers Report aimed to gain insights into the mindset of the next generation of lawyers, their experiences and values, and what they would like to change. While nearly two-thirds of the 418 respondents (65%) were willing to work more than 40-50 hours a week, 33% were frustrated by the time it takes to qualify.

Significantly, only 14% expected to stay in the same role for over five years, indicating that the war for talent is set to continue. And when asked what would encourage them to stay in a role, only 22% cited a competitive salary, while 48% were looking for the potential for career development, which scored higher than any other factor.

When asked what motivated their career choices, responses reflected the same priorities. The report concluded: ‘Despite many firms relying on pricey offers to lure talent, money is not the main driving factor for this generation of legal talent; only 17% of respondents cited money as one of the most important motivators in making career choices. The most significant motivators for the majority of respondents are career development and a good work/life balance.’

Baljinder Singh Atwal, who worked at DLA Piper before joining West Midlands Police in November 2020, highlights the mental health issues related to financial pressure on trainees and law firm expectations of NQs. ‘Law students have a challenging academic curriculum and financial hurdles at the LPC (now SQE) stage,’ he says. ‘This can give rise to stress and anxiety for aspiring lawyers, especially if they combine work and study. At the other end of the qualification journey, highly competitive NQ salaries often come with an unsustainable work ethic which leads to burnout, anxiety and stress. It is clear that overwork and the lack of work-life balance has been glamorised in the legal world and, unfortunately, the salary wars contribute to that.’

The report identified the frustration around qualification and reward: ‘I’m beginning to think that the time, money, and energy it takes to qualify isn’t worth the stressful job at the end of it,’ said one respondent.

Funding the SQE

The fastest route to qualification is a law degree followed by a vocational course and a training contract. There are several routes via the Solicitors Qualification Examination (SQE), for graduates in law and other subjects. Apprenticeships give school-leavers the opportunity to enter the profession without a degree. Part-time study options such as the Chartered Institute of Legal Executives’ (CILEX) blended learning programmes for school-leavers, graduates, law graduates, paralegals and career-changers allow people to work while they qualify. But this prolongs the time it takes to make the grade: and therefore compounds the cost burden, as well as the demands of combining work and study. The CILEX website states that the cost of qualifying as a CILEX lawyer (for a school-leaver or graduate in a subject other than law) is £12,500.

Furthermore, SQE fees are set to rise in October from £3,980 to £4,115, and there are additional financial risks. After a 14-day cooling-off period, there are strict cancellation policies. If a student has to miss an assessment, they are required to pay 75% of the fee, or 100% of the fee for cancellations less than 48 hours before an exam.

Full fees apply to all resits – which will be a common financial outlay given the pass rate at SQE 1 was just 53%.

However, SQE fees are only part of the cost involved in qualifying into the profession. There are costs associated with SQE preparation, and most trainee solicitors have also had to fund at least one university degree. And then there is the rising cost of living. All of this needs to be considered when deciding how and where to qualify, as well as finding a training path that reflects career goals and aspirations.

‘I would say more than ever that this is about cost,’ says Mary Bonsor, CEO and co-founder of interim legal resourcing platform Flex Legal. Her company offers the Flex Trainee scheme, which is designed to help create a more accessible, diverse and socially mobile profession. ‘All our graduates left university £60k in debt due to student loans for tuition fees and maintenance, so they need to get into work before they can think about qualifying as a solicitor,’ she notes.

Baljinder Singh Atwal, in-house solicitor at West Midlands Police, represents the Junior Lawyers Division (JLD) on the Law Society Council. ‘The financial implication is definitely part of the conversation for everyone,’ he says. ‘After university you have to fund the LPC (now SQE). If you have a training contract, this may be sponsored by your firm, but people without training contracts may take out additional loans to pay for vocational training. This steers people in the direction of working in other jobs to save up or studying part-time. It is a tricky time for law graduates as most are still paying off their undergraduate student loan.’ He adds that the promise of a well-paid job post-qualification goes some way to compensate for this.

Bonsor agrees that financial considerations may have contributed to the average age of qualification rising to 29. ‘University debt and the fact that SQE assessments are not covered by student finance,’ she says, ‘will lead to a much bigger uptake of part-time courses that allow people to study alongside working.’

Victoria Cromwell, senior director of business development at e-learning provider BARBRI Global, says: ‘People who are unable to secure a funded training contract will cover the cost by earning while they are learning and accruing qualifying work experience (QWE) at the same time as studying towards the SQE.’ There are also other funding options, she adds: ‘For example, BARBRI offers interest-free loans through an organisation called Knoma, instalment plans and scholarships.’

Costs are not the only factor pushing up the average age of qualification. ‘After the undergraduate law degree, education fatigue can set in and people take a break to pursue other endeavours,’ says Atwal. ‘Additionally, there is a belief that the current undergraduate law degree is purely academic and provides no practical skills for legal practice, so many postgraduates are looking for hands-on work experience before starting their legal career.’

Barrier to social mobility

Law Society president I. Stephanie Boyce responded to the SQE fee increase by expressing concern about the potentially negative effect on social mobility within the profession that increasing the cost of qualification would have.

Atwal agrees: ‘The cost can be off-putting. As a large number of people are not entering the profession because of the cost, we do not have a representative profession which reflects society. This creates an imbalance between lawyers and the clients they serve.’ And the cost of legal education may also be contributing to the talent shortage. ‘A lot of postgraduates seek employment elsewhere, and by the time they have saved enough to pay for training, they will have established themselves in other fields,’ he adds. ‘This is why it is important to talk about diversity and inclusion at graduate recruitment level.’

Jazmin Perry, a solicitor at Boyes Turner in Reading, also sees cost as the biggest barrier to social mobility. She qualified in October 2021 via the traditional pre-SQE route –a law degree from UWE immediately followed by the LPC while completing her training contract at a Cotswolds firm. She joined Boyes Turner’s property disputes team in February.

Perry comes from a low-income, single-parent family. She says that if she had been an SQE candidate she would have been unable to afford any retakes, had she needed them, whereas more privileged candidates can pay for multiple attempts. Because she opted for the LPC as part of a master’s degree (LLM) she was eligible for student finance for the LPC. This she studied for part-time alongside her full-time training contract. ‘I was lucky to be awarded a training contract, as there are so many applicants for a limited number of them,’ she reflects. ‘I am also lucky that I have a stable home, which is a safety net.’

After two years of living from month to month on a postgraduate student loan and a trainee salary, money was important for Perry when it was time to look for an NQ position, but it was not her top priority. She was more focused on her career plans, the quality of the firm and its location. ‘I knew I wanted to do property disputes, and I when I was at university I had applied for Boyes Turner’s vacation schemes,’ she says. ‘So, when I decided to move back to Reading, it was my first choice and, fortunately, I was able to apply for a role there.’

As a large number of people are not entering the profession because of the cost, we do not have a representative profession which reflects society

Baljinder Singh Atwal, JLD

Career-changers and apprentices

But not all firms offer money as a substitute for opportunity or diversity. Weightmans in Liverpool offers opportunities to diverse talent, including career changers and apprentices, and supports them throughout their training.

Michael Westcott has just qualified as a solicitor. But he has worked at Weightmans since 2011, initially as a costs draftsman. While he paid for his part-time graduate diploma in law (GDL) at the University of Law in Manchester in 2016, Weightmans funded his LPC, which he also studied part-time, as part of his training contract. Although the time and cost of qualifying mid-career represented major commitments, Westcott benefited from Weightmans proactively supporting his professional development. ‘When you’re studying while working full-time in a law firm, the financial commitment is easier,’ he explains. ‘I could afford a loan to pay for the fees and Weightmans gave me study and exam leave. The firm has a dedicated career development team to support trainees and NQs.’

Westcott had to go through the same application process as Weightmans’ external candidates and had no guarantee of a training contract. While the financial risks were perhaps less significant for him, the career risks were higher, as he had committed to qualifying as a lawyer while already working for the firm.

Legal apprentices – the next NextGen?

Weightmans also runs a legal apprentice scheme, paying for school-leavers to qualify as solicitors via the SQE route. Westcott, who acts as a mentor to one of the firm’s apprentices, explains the process. ‘It’s a six-year, on-the-job training course, with four years working in different teams around the firm,’ he says. That is followed by what is almost a traditional training contract of four six-month seats in different departments alongside the SQE assessments. The legal apprenticeship, he adds, ‘is a no-brainer for a school-leaver compared with the traditional route of studying law at university’. Weightmans pays them to qualify, covers their fees and facilitates their learning.

At Weightmans the legal apprenticeship offers a solution in terms of investing in young people. It covers their SQE fees and gives them qualifying work experience and on-the-job training. This is facilitating diversity and social mobility in a way that the traditional LPC and the new SQE route cannot achieve because of the financial burden they place on trainees.

Weightmans’ commitment to training, career development and inclusivity is rewarded by low associate turnover. ‘While money is an important consideration, the culture is the main reason I stick around,’ says Westcott. ‘When I was considering joining Weightmans in 2011, I had another job offer paying 50% more. I chose Weightmans because of its culture and, 11 years on, I know I made the right choice. Every six months the firm does job satisfaction surveys, and we are asked for the words we associate with the firm. The one word that appears in every word cloud is “family”. Although Weightmans is a top-45 law firm, it retains a feeling of family.’

And allowing for a work-life balance instead of requiring a 15-hour day opens up other opportunities for career development. These include mentoring, corporate social responsibility and charity work.

Like the respondents to the Future Lawyers Report (see box), Westcott prioritises career development and an employee-centric culture over money. Money alone cannot win the war for talent.

Joanna Goodman is a freelance journalist

No comments yet