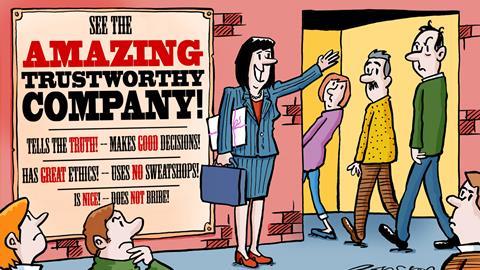

Big companies are struggling to retain the trust of those they depend on, which is destroying value in tangible ways. Should they be listening to their lawyers? asks Eduardo Reyes.

How do I know I can trust you? It is a question any on-the-ball parent has asked their child following the discovery of a simple deception or a broken promise.

The parent’s stern tone might betray anger at the deception. Sitting behind the reaction though is also anxiety – the questioner is likely thinking of their child’s future, knowing how much harder life will be for them if they cannot be trusted out in the big wide world. With trust comes freedom and the help of those you need.

Those who know their history may even have an 1865 quote from Abraham Lincoln at the back of their mind: ‘If once you forfeit the confidence of your fellow citizens, you can never regain their respect and esteem.’

The things that trust bestows and, by extension, that which its absence removes, have placed it firmly on the radar of the business world.

This is why, a few weeks ago, I was sat opposite Baker & McKenzie partner Bea Araujo in the global firm’s staff canteen. Araujo, it turns out, has been thinking hard about trust and the law.

That the large canteen is close to empty would seem to testify to the number of matters Baker & McKenzie lawyers have in their in-trays. Araujo has had time to ponder this big business question because she ended her term on the firm’s global board. An early task she had was a presentation to the firm’s global partners conference.

The topic she chose was ‘trust’ – something she notes ‘arrives on foot, and leaves on horseback’ – and the positive response she received encouraged her to do further work. She paints a picture of a corporate world where ethics, for example, are migrating from a list of items boosting ‘compliance’, to one that is concerned with ‘performance’ and ‘value creation’.

The annual Edelman Trust Barometer, to which she alludes several times, puts the problem for larger businesses starkly: when it comes to trust, family-owned and small and medium-sized businesses outperform big business in all regions of the world excluding Asia.

‘The business case that high levels of trust can foster increased and sustainable profits already exists. So the argument does not have to be remade from scratch,’ Araujo notes. What could be pushed more strongly is the argument that lawyers are central to improving trust. That is important, she adds, because ‘the lawyer approaches it from the perspective of thinking about what is good for the business in the long term, rather than just coming in with a short-term, tactical perspective’.

To understand the importance of that lawyer perspective, she and colleagues have invested time in identifying what has undermined trust for clients. Prominent in the resulting Trust Matters report is a piece of 2013 research from the Institute of Leadership and Management. This showed that nearly two-thirds of managers had been asked to do something contrary to their own ethical code, and just over half had been expected to behave at work in a way that made them feel morally uncomfortable.

Trust in numbers

Businesses

- 63% of managers say they have been asked to do something contrary to their own ethical code at some point in their career, the Edelman Trust Barometer found.

- 51% of managers say they have been expected to behave at work in a way that made them feel morally uncomfortable at some point in their career.

- On measures of trust, family-owned and small and medium-sized businesses outperform big businesses in every region of the world except Asia.

- The World Economic Forum estimates that corruption adds 10% to the cost of doing business globally.

Leadership

- Trust in CEOs stands at 39%, according to the Edelman Trust Barometer.

- PwC’s global CEO survey found that 50% of UK business leaders are ‘somewhat’ or ‘extremely’ concerned that a lack of trust in business threatens the growth prospects of their business.

- The CIPD found that 34% of employees have a ‘weak’ trust in senior managers.

The digital age

- Research by Orange in 2014 found that 78% of Europeans think it is hard to trust companies when it comes to the way they use consumer personal data.

- At 65% and 63% respectively, traditional media and search engines are the ‘most trustworthy’ sources of information, the Orange survey concluded.

The supply chain

- Only 50% of UK manufacturing companies are auditing their suppliers for child workers, slaves and conflict minerals, Achilles research noted in 2014.

- Accountants EY surveyed procurement managers and directors, 52% of whom do not vet suppliers’ compliance with the UK Bribery Act.

The causes of distrust extend to digital-age issues such as use of personal data and the need to keep child labour out of a business’s supply chain. Distrust can be fuelled by corporate mergers that ignore stakeholder views, dubious tax arrangements or a poor environmental record. Being caught engaging in bribery and corruption – well, that goes without saying.

So the impetus is there. ‘There are companies looking at their trust levels,’ Araujo notes, ‘not necessarily reporting on them… but certainly boards are undertaking surveys via third-party researchers to assess their trust levels with their stakeholders.’

This tends to happen, she adds, where a company has ‘undergone a major crisis, and is working its way out of it and rebuilding its reputation, rather than as an integral part of their reporting long-term’. She adds: ‘I am hopeful that we will get there and feel strongly that those companies subject to the Corporate Governance Code will be grappling with these issues in framing their longer-term viability statements.’

How ‘elbows-out’ does a lawyer need to be to assume, or even lead, work on issues that are now being labelled ‘trust’? It should not be presented as a radical change, Araujo urges: ‘The lawyer is reinforcing the message by supporting boards in their decision-making in a way that not only ensures that they comply with all applicable regulation, but also that they are doing so in an ethical way. The lawyer can reaffirm that it is not just about compliance or box-ticking. It is about doing the right thing.’

At one level the basic proposition sounds obvious and uncontroversial – ‘part and parcel,’ consultant and former T-Mobile general counsel Julia Chain notes, ‘of being part of the management board.’ As a proposition, Chain notes, building trust is part of ‘risk management’ – the defi ning remit of any in-house legal department. Establishing trust in leadership, she adds, is a major focus of corporate coaching exercises.

Not a new idea then – but one which, so the argument runs, benefits from being defined in this way. As Araujo points out: ‘There are plenty of examples out there of companies which have decided to “sail close to the wind” to maximise short-term profits and have subsequently found this to be short-sighted, and lost credibility and the trust of their stakeholders.’

How to lose trust

Trust in a business, Baker & McKenzie’s Trust Matters report concludes, can be lost in the following ways:

- By the presence of corruption;

- Dishonesty;

- A failure to fulfil promises made to stakeholders;

- A lack of transparency;

- Having significant liabilities;

- By the absence of clearly accepted rules;

- Through a rapid pace of change; and

- Using child or slave labour in the supply chain.

This takes us into the hard-nosed realm of investor perspectives. These are changing, Araujo argues, and companies need to respond to that change.

‘Investors do look at how [companies] do things and how they are perceived both internally and externally,’ she observes. ‘I think you only have to look at the recent press commentary around different organisations and their sponsors to see that this is increasing.’ Companies with strong reputations, built on ethical business behaviours, Araujo adds, ‘engender greater trust from investors than those who undertake activities which may not be as ethically defensible as others, regardless of whether or not laws are technically breached’.

She uses the example of companies that have ‘focused on ensuring their supply chains are transparent and ethical’. Their results are often better than ‘those that haven’t had that focus’. That is not just based on anecdote. Trust Matters references 2013 research on supply-chain managers, more than half of whom noted that supply-chain issues had a negative impact on their company’s revenue or profitability in the preceding years.

In 2014, only half of UK manufacturing companies, other research shows, were auditing their ‘first-tier’ suppliers for the use of child workers, slaves and conflict minerals mined in conditions of conflict and human rights abuses, and which are sold or traded by armed groups.

Hence the reality that lawyers need to be more assertive in assuming a role here, and insisting that the correct label for the task is ‘trust’.

‘Lawyers tend to be creatures of habit so there will always be some scepticism around new ideas and terminology,’ Araujo admits. But she adds: ‘Rather than just taking a short-term, numbers-only view the lawyer seeks to apply ethical judgements to decisions around what their client is going to do and how they are going to do it – because it is in the best interests of their client for them to do so.’

‘I see it as a return to good old-fashioned lawyering,’ she concludes. ‘It is about listening to your client and assessing more holistically what is in their best interest.’ Building trust ‘is a long-term game’, she adds, but a game that any business that wants to have corporate sustainability has to play.

‘Companies that already have a values-based culture are likely to be better at building high levels of trust, and thus have better prospects of long-term survival and sustainable profits.’

Eduardo Reyes is Gazette features editor

No comments yet