Lethal poison being taken by defendant Slobodan Praljak in Court 1 of Churchillplein 1, The Hague, counts as one of the defining news images of 2017. It was a dramatic end to the work of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) – and for court and detention staff a frustrating one. After all, the court’s record has been phenomenal: it went from indictees moving freely across the former Yugoslavia to all 161 being accounted for through either court verdict or death before a verdict was revealed.

Most reports have stressed that historic achievement, rather than dwelling on security failings that somehow gave former Bosnian Croat commander Praljak access to poison. Such reporting was no doubt informed by the fact that several journalists who had covered the Yugoslav conflict had given evidence against Praljak at trial.

Praljak’s crimes included crimes against humanity, violations of the laws or customs of war, and grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions. That Praljak’s suicide, which followed confirmation of the 20-year sentence he had sought to appeal, was viewed by his nationalist supporters as a noble act of defiance underlines a central fact of life at The Hague tribunals.

For these are not trials to sweep up dusty corners of history. To work in an international criminal tribunal is to deal with the world’s live dangers.

Yet the ICTY’s courts, built into old insurance headquarters, are now receding into the past – and in some cases have been converted to archive rooms.

Half an hour away, in a suburb of The Hague and distant from the diplomatic community that resides around Churchillplein 1, is a quite different building. The International Criminal Court perhaps lacks the improvised charm of Churchillplein 1, but it is quite a statement of intent – a large, fortress-like building with an indelicate relationship to its surrounding streets. Oude Waalsdorperweg 10 is the face of a new type of international justice.

The ICTY and the subsequent Rwanda and Lebanon tribunals required a Security Council mandate to operate. That is impossible to establish for theatres of conflict where any permanent member has an interest and expresses that interest by wielding a veto. Attempts to establish a tribunal covering aspects of the conflict in Ukraine were vetoed by Russia, for example.

The ICC, by contrast, should be a standing court whose prosecutors have a much freer hand to investigate and seek indictments. The Security Council can refer a matter to the ICC, and the ICC may ask the Security Council to act in its support; moreover, the ICC’s authority comes from the Rome Statute, an international treaty that now has 124 signatories.

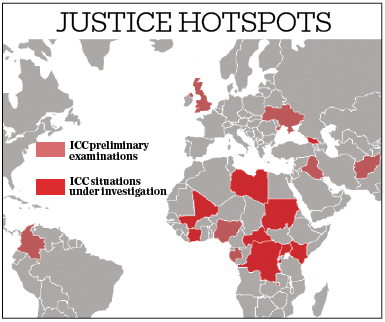

The ICC’s investigations are indeed wide-ranging. It has eight ‘preliminary investigations’ currently open, including Iraq/UK, Ukraine, Palestine, Nigeria and Colombia. Several involve states where Security Council members have vested interests.

Situations ‘under investigation’ encompass Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Darfur (Sudan), Central African Republic, Kenya, Libya, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Central African Republic II, Burundi and Georgia. Sudan and Libya were referred by the Security Council.

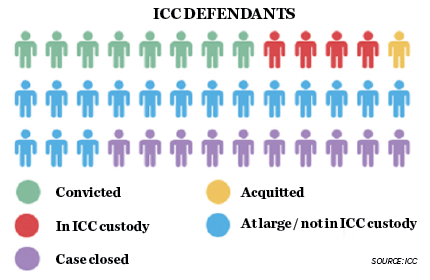

To the ICC’s critics, that is a list with a suspiciously pronounced focus on Africa. Of the 42 defendants named in cases, all allegations relate to events in African states. This is an issue that poses a threat to the ICC’s credibility on the continent – but although Gambia, Burundi and South Africa tried to test that credibility by stating an intention to withdraw from the Rome Statute, others did not follow.

What South Africa, Burundi and the Gambia seek is a return to expediency. South Africa’s notice of withdrawal admitted as much. ‘The Republic of South Africa is committed to fight impunity and to bring those who commit atrocities and international crimes to justice,’ international relations and cooperation minister Maite Nkoana-Mashabane wrote. But she added that her country ‘has found its obligations with respect to the peaceful resolution of conflicts at times are incompatible with the interpretation given by the International Criminal Court of obligations contained in the Rome Statute’.

South Africa had ignored a tribunal order to arrest Sudanese president Omar Hassan al-Bashir, who made open visits to the country. The rule of law, South Africa decided, cannot be allowed to interfere in regional power play. A similar judgement was made by Jordan (see below).

Portraying the ICC as ‘anti-African’ has drawn some blood – a few minutes spent looking at the continent’s press commentary makes that clear.

Set against that are the contrary views of civil society organisations (especially strong in the case of South Africa) who note that it is crimes against Africans that have led to such apparent over-representation in the indictment lists. As Amnesty International put it, ‘for many Africans the ICC presents the only avenue for justice for the crimes they have suffered’.

The court, and international justice itself, are young, points out veteran international tribunal judge and advocate Geoffrey Robertson QC. Expectations are high, he tells the Gazette, but the road to justice can be long.

It is important to remember that 50 years passed before any delivery on the Nuremberg legacy, which began with the ICTY, and it was not until this century that international justice started in earnest

- Geoffrey Robertson QC

‘It is important to remember that 50 years passed before any delivery on the Nuremberg legacy, which began with the ICTY, and it was not until this century that international justice started in earnest,’ he argues. ‘So it’s really too early to give up on it.’

This brings Robertson to the role of the Security Council, which retains a key role in the ICC. ‘The key to its future lies with the Security Council,’ Robertson notes. ‘Court supporters are often frustrated; Syria being the obvious case in point.’

He recalls: ‘In 2011, after 800 peaceful protesters had been cut down by Assad’s brutal troops, I wrote an article urging a Security Council referral to the ICC. That did not come for four years [by which time] 400,000 were dead… when Britain did propose it, it was of course vetoed by Russia. I remember how those peaceful protesters held up banners reading “Assad to the Hague”.’ The ICC, he says, ‘had created cruelly unrealistic expectations’, yet ‘we should not be overly pessimistic’.

Out of Africa: a who’s who of convictions

Al Faqi Al Mahdi, Ahmad

Alleged member of Ansar Eddine, a movement associated with al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, head of the ‘Hisbah’ until September 2012, and associated with the work of the Islamic Court of Timbuktu.

Found guilty as a co-perpetrator of the war crime consisting in intentionally directing attacks against religious and historic buildings in Timbuktu, Mali, in June and July 2012. Sentenced to nine years’ imprisonment, with the time spent by the suspect in detention being deducted from the sentence.

Arido, Narcisse

National of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Found guilty of various offences against the administration of justice related to the false testimonies of defence witnesses in the Bemba case (see below). Case also involved charges against Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo, Aimé Kilolo Musamba, Jean-Jacques Mangenda Kabongo and Fidèle Babala Wandu.

Babala Wandu, Fidèle

National of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, member of parliament in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Found guilty of various offences against the administration of justice related to false testimonies in the Bemba case. Case also involved charges against Bemba Gombo, Kilolo Musamba, Mangenda Kabongo, and Arido.

Bemba Gombo, Jean-Pierre

President and commander-in-chief of the Mouvement de Libération du Congo, at time of warrant.

He is appealing two counts of crimes against humanity: murder and rape; and three counts of war crimes: murder, rape and pillaging, allegedly committed between 2002 and 2003 in Central African Republic.

Katanga, Germain

Alleged commander of the Force de Résistance Patriotique en Ituri (FRPI) at time of arrest warrant.

Found guilty, as an accessory, of one count of crime against humanity: murder; and four counts of war crimes: murder, attacking a civilian population, destruction of property and pillaging. Case also involved charges against Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui but the two cases were severed on 21 November 2012. Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui was acquitted on 18 December 2012.

Kilolo Musamba, Aimé

National of the Democratic Republic of the Congo; former defense counsel for Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo.

Found guilty of various offences against the administration of justice related to the false testimonies of defence witnesses in the Bemba case. Charged together with Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo, Jean-Jacques Mangenda Kabongo, Fidèle Babala Wandu and Narcisse Arido.

Mangenda Kabongo, Jean-Jacques

National of the Democratic Republic of the Congo; a former defence team member of Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo.

Found guilty of various offences against the administration of justice related to the false testimonies of defence witnesses in the Bemba case. Charged together with Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo, Aimé Kilolo Musamba, Fidèle Babala Wandu and Narcisse Arido.

Source: ICC

My enemy’s friends

One battle the ICC must win is to answer fully the accusation that its cases are not fairly conducted. This is an unenviable position for the criminal court. On the one hand, when it investigates or indicts those who have the power to evade its justice, it appears impotent. Where it has a defendant in custody, facing trial, that can be because the political winds have changed – opening the ICC to the (albeit contested) charge of administering the justice of victors only.

Where the latter appears the case, all emphasis is on the ability to provide a trial that is seen to be fair, and where procedures and resources for each side match the just demands of the task in hand.

So, do the established procedures and norms allow for a fair defence? US lawyer Peter Robinson is licensed to appear as an advocate in all the existing international criminal tribunals. Notably, he was counsel for ex-Rwandan minister Dr Augustin Ngirabatware in part of his appeal, when one of Ngirabatware’s judges was detained by the government of Turkey, delaying appeal hearings (Gazette, 22 December 2016).

‘The Statute and rules are good,’ Robinson ventures. ‘The challenge is to apply them fairly in the face of the presumption of guilt that exists in international criminal cases due to media coverage and civil society demands.’

The resources required for defence of war crimes or genocide will inevitably be dwarfed by those required by the prosecution. The cost of gathering evidence – for example, excavating a mass grave and documenting witness testimony – is more than that required to attempt rebuttal of such evidence.

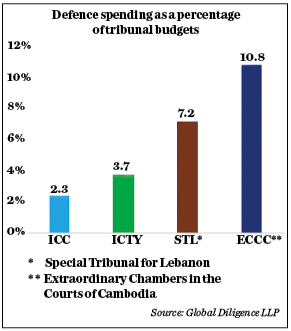

Nevertheless, Robinson notes, there are concerns about the disparity of resources available in ICC cases. ‘A recent study showed that the ICC provided fewer resources to the defence than the ad hoc tribunals,’ he adds. Research shows the ratio of legally aided advice ICC defendants can call on compared to defendants at other international tribunals – concerning Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Lebanon and Cambodia – is smaller.

Robinson is citing analysis by Richard Rogers, a distinguished international lawyer whose clients include the Foreign & Commonwealth Office. This concluded that ICC defence cases were underfunded. Rogers’ report for the public interest legal body Global Diligence noted that total defence spending as a percentage of ‘total court budget’ was 2.3% for the ICC, well behind the Yugoslav tribunal (3.7%), and Lebanon (7.2%). It was 10.8% for Cambodia, though the Cambodia tribunal was set up on different terms, sitting ‘in-country’ (see box, above).

Notions of what constitutes a fair procedure are evolving and can differ depending on whether an advocate acts for the defence or the prosecution. Transparency is also an issue.

The tribunals, the ICC included, allow for ‘live’ broadcast, albeit with a time delay that allows content that should not be broadcast to be stopped. The broadcast rules are strict. Whereas in the 1961 Israeli trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, close-ups were allowed in the hope of showing (say) the accused feeling the pressure of cross-examination, modern tribunal camera crews produce shots that seek not to ‘dramatise’ proceedings.

As ICTY audiovisual producer Rob Barsony told the Gazette previously: ‘We must choose the most objective shot. We are a raw footage provider, therefore everyone can manipulate our material. So we want to give them, as a starting point, the most objective material.’

Barsony added: ‘Some don’t like me for refusing to do a close-up of a shaking hand, or a witness or party who is sweating. Cameras can enhance emotion, creating an emotional disparity.’

The flick of an electronic button makes curtains descend and the court moves to closed session. This is common to all international tribunals.

Yet, while the audiovisual unit has standards of objectivity, Robinson still has criticisms; those electric curtains at times present problems. ‘Transparency is improving,’ he notes. ‘But some judges and administrators still have a mindset of protecting the image of the court at the expense of transparency. There remain too many confidential filings and closed proceedings.’

A by-product of the complexity of cases – and of the combination of different legal traditions that the ICC and preceding tribunals have synthesised – has been a growing reliance on paper submissions. This cuts against the Anglo-American common law tradition of ‘orality’ in proceedings.

Is that a problem? ‘Yes,’ Robinson argues. ‘Evidence that cannot be tested cannot be safely relied upon.’

Yet, inevitably, some say procedures allow defendants too much latitude for extending proceedings. They point to the flurry of filings that occurred ahead of Ratko Mladic’s judgment and sentencing late last year. There were more than 20 in the final few days, though in that case the judgment date of 22 November was not delayed as a result.

Robertson comments: ‘The procedures must be improved as they permit too much delay and expense.’

The challenge for the ICC, it could be argued, is to ensure procedures operate to a satisfactory timetable, while also levelling the playing field when it comes to an appropriate balance between prosecution and defence counsel. Of course, some time delay in achieving a determination relates to the fact that indictees can spend years or even decades ‘at large’.

Just future

In the very different context of UK public spending cuts, it has been observed that it is much harder to axe a service when it has a building attached. Applied to international criminal justice, that may render the ICC’s imposing headquarters an asset, and not just a cost to be criticised.

Does the court have ‘reach’ that goes beyond the backing it receives in individual cases? Can it be more than the sum of the international community’s appetite for expediency or impunity?

Arguably, yes. While Sudan’s president seems to wander Africa and the Arab world with impunity, Kenya’s president Uhuru Kenyatta succumbed to the pressure to attend the court for charges relating to the conduct of his own election. Those charges were dropped.

ICC chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda made a show of reluctance as she withdrew allegations in 2014. She told the court: ‘Given the state of the evidence in this case, I have no alternative but to withdraw the charges against Mr Kenyatta… I am doing so without prejudice to the possibility of bringing a new case should additional evidence become available.’

From an ICC perspective, Kenyatta was, at least, present to hear the decision.

The ICC is apparently learning too, not least from the ICTY – whose shadow some say it emerges from with a degree of insecurity. ‘The ICC has preferred to blaze its own trail, rather than learning from the ICTY,’ Robinson relates. ‘At the beginning of the ICC’s operation, the insistence on doing it their own way made it politically incorrect for ICC staff who had worked at the ICTY to say “this is how we did it at the ICTY”. That was like a faux-pas. The court’s administration and judges were determined to reinvent the wheel. That has lessened somewhat over the years as the ICC stumbled and lessons from the ICTY are a bit more tolerated now.’

But as was the case with the ICTY, the biggest difference to its record would come from a shift in international political priorities. As Robertson concludes: ‘There is nothing wrong with the ICC laws, subject to the failure of the member states to bring within its jurisdiction the crime of aggression… the key problem for the ICC is its lack of support and particularly the lack of support of its prosecutor from a frequently pole-axed UN Security Council.’

1 Reader's comment