A solicitor’s memoirs – part 1

In 1939 Edward A. Bell wrote his memoirs. These Meddlesome Attorneys is an account which takes the reader from Bell’s childhood as a solicitor’s son, to his early legal practice in 1890s London, 30-plus years on the Law Society Council, and his thoughts on how men and women should pass their time in old age.

My interest in Bell started with his support for women’s entry to the profession. He was a witness in Bebb v The Law Society, where he testified that if Gwyneth Bebb won her case, he would offer her articles. Last week, on a visit to Cambridge’s university library, I found he was alone among the vocal supporters of women’s admission on the Council in having published his memoirs.

In fact he does not mention the Bebb litigation, and his friendship with the Pankhursts and efforts for the women at the Law Society Council takes up just a page and a half. But having recently interviewed lawyers in Ukraine on their efforts to carry on through the war with Russia, I was drawn to his chapter on ‘The Legal Profession in the Great War’.

‘The sudden thunderbolt disaster of war resulted in a bouleversement of the old rhythmic order of legal as well as business affairs,’ Bell begins. The effect on the profession was immediate, he recalled: ‘In the City of London during the first weeks in August 1914 banks withheld payment except for wages and salaries. A moratorium – a new word for most people – postponed the compulsory payment of debts, and in truth it was a hand-to-mouth experience.’ A ‘heavy payment’ he received the day before the moratorium tided him over.

‘All the younger officials were “falling in” at Kitchener’s call,’ he wrote, ‘and retired men were brought in to take on their duties during hostilities. The dear fellows took time to regularise their old fashioned knowledge of procedure with the routine practice which had evolved since their retirement.’

The law courts in the Strand provided a drill hall for military training in 1915 and 1916, Bell noted: ‘During the winter months the Great Hall was a drill-ground by day, and Colonial troops on their way through London used the Hall as a dormitory by night… Another part of the Law Courts was partitioned off and used for the Postal Censor’s department.’

Bell joined the City Police Force as a ‘special’, combining duties such as night patrols with his daytime practice – a friendly court official providing him with a sofa in the judge’s quarters in the Royal Courts of Justice to rest on nights when he did not have time to return home.

The ideal for a lawyer on patrol as a special was to be paired with another lawyer, such that: ‘Legal practice and procedure became the topic of many midnight conversations.’

In between such deliberations, they were among the first to encounter troops returned from the front. ‘The “leave” men’s rail-head was Victoria and no facilities were provided to transport them across London to other railway stations. Leave trains generally arrived at midnight and many mud-plastered soldiers found their way towards Liverpool Street and Fenchurch Street termini. The “specials” used to help them along… Some… were in a state of stumbling collapse.’

With so many legal professionals serving, the impact of the law was marked. ‘The professions were almost merged, solicitors being allowed when counsel were absent to fill counsel’s place and conduct cases in open court,’ Bell wrote. And the business of the courts changed too: ‘Much of the civil business of the Emergency Orders was transacted before tribunals set up by war legislation.’

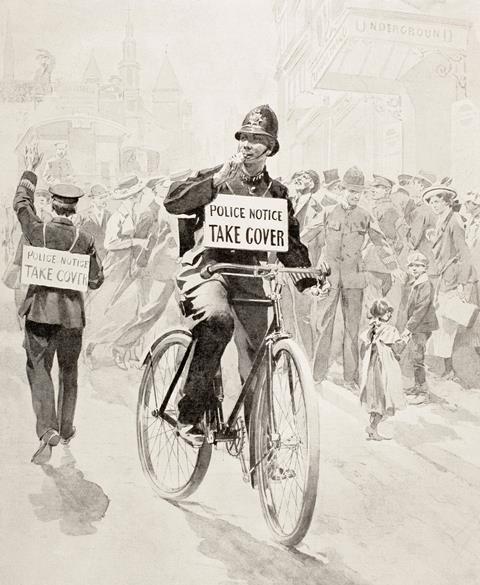

The police courts had fewer ordinary crime cases, ‘and much of the magistrates’ time was taken up with the consideration of infringement of the lighting orders, a citizen’s residence being required to screen interior light, a war curfew prevailing throughout the land. The Police Courts, during the submarine menace, had jurisdiction over infractions of the rationing of “food tickets”, tradesmen and customers being alike under penalty for supplying or eating more than the regulated food quota’.

He recalled that proceedings before the Military (Conscription) Tribunals, and City Tribunals (where appeals were heard), had wide discretion in their decisions (conscription was introduced in early 1916). The standard of evidence and interrogation varied. ‘Where the appeals were chiefly by mercantile clerks, the rough rule seemed to be to allow married ledger clerks to remain, assisted by women; all the other male members of staff were required to join up,’ Bell wrote.

The tribunal at first allowed many appeals ‘if the appellant agreed to join the special police force’, Bell noted, but ‘during the last year of the war the young special constables were sent into the army direct from the police’. The final court of appeal on conscription was the House of Lords Military Tribunal. Even at this high level, discretion was exercised according to some unofficial criteria. If Sir Donald McLean was the chairman, Bell said, there was ‘observable leniency, helping married men over the stile by adjourning the hearing for long periods to allow their unmarried colleagues to proceed into the army before them’.

Bell had a military tribunal appeal hearing scheduled for 11am on 11 November 1918, where he was ‘to support an appeal on behalf of a middle-aged butler’. Instead, with the armistice confirmed: ‘In a split second the Tribunal adjourned and the street became a torrent of cheering rushing humanity which surged towards Trafalgar Square.’

It was the end of Bell’s war – time for him to return to his long life in practice and a highly active role on the Law Society Council.

Edward A. Bell, These Meddlesome Attorneys, was published by Martin Secker, London in 1939

2 Readers' comments