Janet Skinner was 35 and a divorced mother of two teenage children in 2007 when she was accused of stealing almost £60,000 from the busy post office she ran on a council estate in Hull.

Last month she was one of 39 former postmasters cleared of similar offences after it emerged the Post Office had failed to disclose that a defective computer system installed at their branches was generating ‘phantom’ transactions. Initially charged with theft, Skinner pleaded guilty to false accounting despite knowing she had not taken the money. Her lawyer had advised this as her best hope of avoiding a custodial sentence.

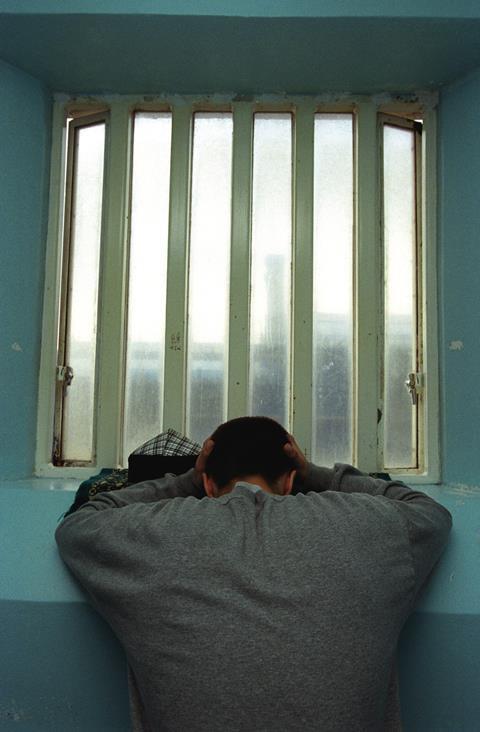

‘I did it out of fear,’ she tells the Gazette. The thought of prison terrified her. ‘I was the main carer for my children, my son was only 14. They needed me.’ Skinner says she was naive and had little idea of the impact the conviction would have on her. ‘Crime isn’t my thing… I didn’t know what I was letting myself in for.’

Not only did Skinner receive a nine-month jail sentence despite her plea, she was given an £11,000 confiscation order and told to pay the same amount as compensation to the Post Office. She was threatened with a further five years in jail before the court accepted that she was genuinely penniless. She has not worked since her conviction, as job applications require her to disclose her criminal record, and she suffers from a serious autoimmune disease which she feels is probably linked to stress.

Her lawyer at the time, Karl Turner – now Labour MP and shadow justice minister – tells the Gazette he is confident his advice to Skinner was correct, given the apparent strength of the evidence against her and the fact some postmasters in similar situations who did opt for trial were found guilty. ‘We didn’t know at the time that the Post Office were lying bastards,’ he says.

I’ve had someone say they took the rap for their brother, who had never been in trouble before

Stuart Nolan, DPP Law

Turner, who worked as a criminal defence barrister for five years before entering parliament in 2010, thinks the postmaster cases are unique because of the Post Office’s behaviour and its dual role as investigator and prosecutor. Under normal circumstances he feels it is very rare for clients who are innocent to plead guilty and that the bigger issue is the short amount of time defence lawyers have to advise their clients.

Under current sentencing guidelines, defendants are given sentences discounted by a third automatically if they indicate they will plead guilty ‘at the first stage of proceedings’, with a sliding scale of reduction from one-quarter to one-tenth for later pleas. The guideline explains that early pleas are in the public interest as they save time and expense while also sparing witnesses the trauma of testifying.

‘Credit of a third off is not an incentive for the innocent to plead guilty,’ Turner adds.

Thumbscrew courts

But the Gazette spoke to one criminal defence lawyer (who asked not to be named) who thinks ‘thumbscrew courts’ – hearings in which the judge persuades the defendant to plead guilty by indicating likely sentence – can push people into accepting responsibility for crimes they did not commit.

‘I’ve heard case management hearings referred to as “pressure to plead” hearings,’ said another.

Stuart Nolan, criminal defence lawyer and managing director of DPP Law, recalls a plea and trial preparation hearing for a client with no previous convictions. ‘The evidence was pretty compelling,’ he says. On hearing the defendant was pleading not guilty, the judge said: ‘On her head be it if she wants to dig a bigger hole for herself,’ Nolan recalls. In his view, ‘that could be construed as if pressure is being applied’.

Nolan, who practises in an urban area of Liverpool, believes some clients have accepted responsibility for crimes because they lack faith in the justice system and think they won’t be believed. ‘Nobody has told me categorically that they didn’t do it but that they want to plead guilty anyway,’ he said. ‘I could not put that to the court as by pleading guilty they have to accept the Crown’s case.’ But clients have told of their innocence after the event. ‘I’ve had someone say they took the rap for their brother, who had never been in trouble before.’

TURNING BACK THE CLOCK

A recent Court of Appeal case – Plaku and ors v Queen – considered the correct approach to sentencing discounts for early pleas. It highlights a distinction in the guideline between those who need more information about the case against them before pleading and those who hold off until they can see the strength of the Crown Prosecution Service’s evidence. For example, someone who delays while they wait to find out if certain evidence is admissible cannot expect to be given full credit if they only plead guilty once the admissibility issue is resolved against them.

Reacting on Twitter, one defence lawyer said the judgment illustrated the Court of Appeal’s lack of understanding of the magistrates’ courts.

@neilsnds tweeted: ‘Very often there is little or no evidence served at the MC. If the solicitor acting was not in the police station then they may have nothing substantive to advise on… a client may be facing a matter that could lead to a long prison sentence and their lawyer – who will be almost constantly harried by the court to hurry up – will be expected to advise them based on no evidence.’ To do so would be negligent, he added. ‘In effect this judgment takes us back to the days of “your client knows if he’s done it”, and “if the CPS have charged it then he must’ve done it”. That is not justice, that’s just expediency to save money.’

Under pressure

Rebecca Helm, law lecturer at Exeter University, says research dating back to the 1970s shows ‘false’ guilty pleas – guilty pleas from defendants who are factually innocent – are likely to be occurring. Many of the cases referred to the Court of Appeal by the Criminal Cases Review Commission initially involved a guilty plea. Examples on Exeter’s Miscarriages of Justice Registry include Thomas Smart, who pleaded guilty to possessing live ammunition following a novelty bullet keyring being found at his home. His conviction was quashed after the Forensic Science Service, which had said the keyring was live ammunition, admitted it was mistaken. Michael Holliday confessed to robbery to police when high on drugs then pleaded guilty on the advice of his lawyer. His conviction was quashed when someone else confessed to the offence.

In 2017/18, Helm surveyed 90 legal professionals. Around 90% said they thought some defendants plead guilty because it is quicker and easier than going to trial, and 61% said these included defendants they thought were innocent.

Helm also found that, despite this, defendants’ decisions to plead guilty were seen as ‘largely rational, autonomous, and consensual’ in the UK because of the absence of large charge and sentencing discounts characteristic of the US system.

However, as in Skinner’s case, a guilty plea can increase the likelihood of a different type of sentence being imposed than would be received if convicted at trial. A jail sentence may be reduced to a community sentence, or a community sentence to a fine. Helm argues this can create a ‘coercive’ incentive for those on remand or who, like Skinner, have particular reasons for avoiding custody such as the need to care for dependants, resume education or retain employment, or simple fear of being imprisoned. Many of the other 39 cleared postmasters had also pleaded guilty and have since said in interviews they did so on the advice of their lawyers to try to avoid jail.

Helm’s research found release from jail for remand prisoners and the costs of trial also acted as incentives to plead guilty. ‘Tactical’ guilty pleas are particularly common in domestic violence cases for those who have been remanded but where a non-custodial outcome is very likely on conviction, one of Helm’s survey respondents pointed out. These defendants are often remanded because they have no other address to offer the court or have already breached a restraining order, so bail becomes ‘problematic’.

Although the offences committed are rarely serious enough to warrant immediate detention, prosecutors are sometimes driven by anxiety over bad publicity in such cases, the respondent suggested, or ‘fear that they are going to be “that prosecutor” who agreed a bail package only to have the defendant seriously harm or kill a complainant’. Remanded in custody, these defendants, whose livelihoods may be destroyed if they remain in jail, are strongly incentivised to plead guilty rather than wait for a trial, the respondent explained.

Homeless people and foreign nationals are also likely to be remanded for relatively minor offences because the courts do not trust them to return to court for trial. ‘Legal regulations aim to limit the occurrence of this but it can still happen,’ Helm adds. These groups are therefore at risk of making ‘pragmatic’ guilty pleas.

Trial delays and extended remand periods caused by Covid mean more and more suspects face spending longer on remand than they would likely receive at sentence if found guilty.

The most recent government statistics available show that the remand population in prison increased by 24% in 2020 to 12,066 – the highest figure for nine years. The data suggests this is partly accounted for by an increase in suspects remanded for drug offences, who now account for 27% of all remand suspects.

The Ministry of Justice does not routinely publish data on the length of time defendants spend on remand, but Fair Trials, a charity that campaigns for improved trial rights in criminal cases, obtained figures under Freedom of Information requests showing 3,608 people had been held for six months or longer as of December 2020, and 2,551 people had been held for eight months or longer. Keima Payton, senior partner of Payton’s solicitors, had a client who was remanded in October 2019. At the time of their bail application in January they had spent 457 days on remand.

In September 2020, the government extended the amount of time someone can be held on remand from six to eight months. Many of the defendants in Fair Trials’ data – and Payton’s client – had already exceeded the new custody time limit when the extension came into force.

Pandemic justice

Guilty plea rates have risen since the start of the pandemic. Government statisticians say it is difficult to draw conclusions from this – it could be due to Covid-related restrictions on jury trials. But Emma Lewis, criminal defence barrister at MK Law, says many of her clients on remand ask how long they will spend in prison if they plead not guilty and it is clear the answer is influencing their decision. ‘I have a client who has been in custody for 10 months and doesn’t even have a trial date yet,’ she says. She feels youth defendants are particularly vulnerable to incentives to plead guilty. ‘Children don’t really understand the implications for their future.’

Fair Trials asked prisoners if they had considered pleading guilty to get out of extended remand while awaiting trial. One of the prisoners who replied had been remanded in HMP Preston due to a recall in March 2020. ‘I had one additional charge of harassment which I was totally innocent of,’ he said. ‘I struggled to have conferences with my solicitor and couldn’t get to speak to my barrister. I managed to speak to him for five minutes on the day of my hearing in which he stated that if I was to plead not guilty then my trial would be put off for a year.’ He considered pleading guilty in order to secure a transfer out of HMP Preston, where conditions were ‘horrible’. ‘My mental health was suffering and I was severely depressed… I am aware of at least four other people who pleaded guilty just so they didn’t have to stay in HMP Preston, potentially until 2022, just to have a trial. It is totally wrong and unjust.’

As Tomas McGarvey, a defence barrister and member of the Criminal Bar Association’s Executive Committee, points out, it is not only those on remand who struggle with the wait for trial. ‘There are people on bail but subject to onerous conditions such as tagged curfews, their [conditions] are very restrictive and they have trial dates that are even further off because people in custody are prioritised.’ He adds: ‘I’ve had two clients where the wait has clearly been factored into decisions to plead.’

But Paul Harris, senior partner of Edward Fail Bradshaw and Waterson, argues the long delays could also act as a disincentive to plead guilty in some cases. He says some defendants on bail may calculate that the prosecution witnesses are more likely to lose interest in the case if the trial date is a long way off. He adds: ‘Prosecutors are now far more amenable to discussing pleas to less serious offences than those charged with a view to avoiding trials because of the huge backlog in the criminal justice system and resulting pressure.’

In August 2020 the Telegraph reported that ministers were considering plans to abolish discounts for early pleas for some serious crimes for fear they are undermining public confidence in the criminal justice system.

But the proposal is ‘unrealistic’, Harris says: ‘There is an element of loss of confidence in the criminal justice system because of huge underfunding in the system in its entirety – in some ways it has never been so good for repeat offenders. These proposals will simply create more big expensive trials and more pressure. They won’t restore confidence, they will increase the backlog and delay.’

Melanie Newman is a freelance journalist